Victims’ families are often extremely reluctant to appear in the media. It can be horribly retraumatizing. Many of us feel we have no choice – that without our voices, the media coverage will be incomplete, imbalanced, or even inaccurate. So we often choose to speak.

While we cannot possibly keep a comprehensive list of media reports that include reference to NOVJM on this website (or NOVJL, our original name), here are some samples of our appearance in the news media:

National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers

Compassion in juvenile sentencing, 2008

Several weeks ago, I spoke with Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins of Illinois.victims.org after she commented on a post I’d done that she felt had portrayed murder victims’ families as vengeful.

That hadn’t been my intent, but after speaking with Jennifer, I realized that my reference to victims’ families in the post had been insensitive.

My stated purpose for the creation of this blog is to create a dialogue, but doing so has proven easier said than done.

I realized that with very few exceptions, there was no conduit for meaningful dialogue between the advocates for eliminating the sentence of Juvenile Life without the Possibility of Parole and the living victims of those inmates serving LWOP for crimes committed as juveniles.

The Pendulum Foundation is an advocacy organization for juveniles convicted as adults. The mission statement on Pendulum’s website is this:

“Children are our most precious natural resource.

The Pendulum Foundation believes in second chances. As a juvenile justice non-profit organization, we are committed to educating the public about the issues surrounding children convicted and sentenced as adults. We are also committed to taking groundbreaking programs and projects into the prisons that will help our incarcerated youth survive and thrive, as well as transform the lives of young prisoners re-entering society and at-risk youth. Our goal is to ensure – whether inside or outside of prison — happy, healthy, well-adjusted and productive adults.”

There is no advocacy organization for the families of murder victims in Colorado. I thought about this and realized how tragic that really is. I thought about what it might feel like to have lost a loved one to a brutal crime and I imagined how hurt and angry I would feel to see blog posts and news articles in support of the offenders, with no thought to the victims’ perspective. Jennifer helped me to understand how truly traumatizing it is for the living survivors. She helped me to understand that the extreme cases of victims’ families who appear to be vengeful tell only a tiny part of the story. What we don’t see is the long term impact that survivors of these terrible tragedies live with. She helped me to understand that in addition to their grief, victims’ families often deal with divorce, depression, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder and that the prospect of having to testify at parole hearings on a recurring basis, therefore reopening the trauma of the crimes is something that has to be considered when debating changes to LWOP sentences.

Historically, there has been no constructive dialogue between “pro-offender” and “pro-victim” advocacy groups and in order to consider changes to sentencing law, this dialogue has to occur.

I just discovered that there is now a new site called The National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

This is an excerpt from the web site, explaining why the site was created:

“The national effort is now well underway by advocates for juvenile offenders to eliminate, or certainly to moderate, the juvenile life without parole sentence for the over 2000 convicted murderers in the United States that were under the age of 18 at the time of their offenses.

While we can understand their well-meaning motives, murder victims’ family members of those cases have, for the most part, been left out of that discussion.

This is not acceptable – to leave the victims of these crimes out of the conversation about what to do with their loved ones’ killers – and will not lead to the broad social change the advocates for the juvenile lifers would hope for, in any case. Unless principles of victims’ rights and human rights and restorative justice are applied to the victims’ families, the social discourse on this sentence for younger killers will degenerate, as it already has in several states, to polarized adversarial battling, resulting in no reforms accomplished and no victims being supported.

Even though there has been a well-funded, fully staffed, orchestrated multi-organizational movement calling for an end to the Juvenile LWOP sentence operating nationally for years, only one state has passed any legislation reforming Juvenile Life without Parole sentences – Colorado.

And Colorado had to pass its law in a painfully adversarial battle with the victims’ families (that knew about the legislative effort to lessen the sentences of their loved ones’ killers). This opposition, we know, saddened and frustrated the conscientious advocates for the juvenile offenders. They have written to us and stated how much they wish that there could have been a respectful and responsible dialogue between them. Instead it was agonizing for all sides.”

I’m encouraged that this new site has been established and is reaching out to contact victims’ families and to offer them voice in this discussion. It’s only when we, as a society are able to examine the complex issue of juvenile life sentences together that we be able to find solutions and alternatives that consider the rights and the humanity of everyone.

Juvenile Life Without Parole

PBS, 2009

O’BRIEN: In Pennsylvania, a Senate committee held hearings last October to consider doing away with life sentences for juvenile offenders. Lawmakers got an earful from opponents like Dawn Romig, whose 12-year-old daughter had been murdered by 17-year-old Brian Bahr.

Ms. ROMIG (testifying): We learned that Brian had made a list. It was called 23 things to do to a girl in the woods: “Beat her, check; rape her, check; kill her, check.” Everything on that list was carried out. It was an adult act he planned and executed. Why should these juveniles not get life in prison? Age cannot excuse what they have done.

JODI DOTTS (testifying): I never got to say goodbye to Kimmie. I never got to see her in a casket. I now talk to her at her grave still, 10 years later, on Mother’s Day. I’d also like to add, as I was sitting here listening to people saying they need second chances, my daughter didn’t have a second chance. She wasn’t given that choice whether to live or to die and I’m here to fight to make sure that these juveniles do not get released. Thank you.

Teens locked up for life without a second chance

CNN, 2009

Proponents of the strict sentencing laws said public safety should be top priority. They argued that judges give certain criminals, regardless of their age, life sentences because the crimes are so abhorrent.

“There are some people who are so fundamentally dangerous that they can’t walk among us,” said Jennifer Jenkins, who co-founded the National Organization for Victims of Juvenile Lifers. The Illinois-based group has fought legislation in nine states that would remove sentences of life without parole.

Jenkins has experienced the devastation of losing family members to a teen killer. In 1990, her sister and her sister’s family, who were living in a wealthy suburb in Chicago, Illinois, were murdered by a teenager.

“Victims have the right not to be constantly revictimized,” she said.

Two cases may change the way teens are punished

CNN, 2009

Allentown, Pennsylvania (CNN) — Sixty miles and the twin tragedies of young lives lost to violence link this industrial hub to the tough streets of North Philadelphia.

Here, a grieving mother uses the memory of her murdered daughter to fight on behalf of victim rights. In his West Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, a paroled teenage killer uses his second chance to mentor at-risk youth. In these separate cases, both the criminals and their victims were juveniles.

Their stories provide the backdrop for an unrelated pair of upcoming Supreme Court appeals over whether juvenile offenders who commit violent felonies deserve tough prison sentences — especially life without parole.

On Monday the justices will examine whether the Constitution’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” should be applied in such cases, and whether young minds, because of their age, have less culpability and greater potential to be reformed.

“These two cases are going to tell us a lot about how far the Supreme Court — led by Justice [Anthony] Kennedy — is willing to go in limiting a state’s ability to impose incredibly tough sentences on either the young, or in some cases, the mentally retarded,” said Thomas Goldstein, co-founder of Scotusblog and a leading Washington attorney. “How much is the Supreme Court willing to intervene here?”

Child was abducted, strangled

On a quiet street in Allentown, Dawn Romig can look out from her porch and see the city park a block away where in 2003 her world fell apart. There on a snowy late February afternoon, her 12-year-old child, Danni, was abducted by a 17-year-old neighbor. The girl was beaten, raped and strangled.

Romig and her husband, Daryl, were in the courtroom when suspect Brian Bahr was brought in for a first appearance. “I leaned over to my husband and I said, ‘Oh my goodness, I know who that is,’ ” she recalled. “I said, ‘I’ve yelled at him. He was a troublemaker in the neighborhood before.’ “

Bahr was tried as an adult, convicted, and given life without parole. Pennsylvania leads the United States in teen lifers with more than 440, according to state lawmakers supporting laws to end such sentences.

Anyone in the state charged with homicide has to be tried as an adult and, if convicted, sentenced to life behind bars.

“He was very close to 18, he was very angry, he knew what he was doing, he knew right from wrong,” Dawn Romig said of her daughter’s killer. “He had a written plan on paper that they found in his school bag, 23 things to do to a girl in the woods. And he did it all.”

–Dawn Romig

She thinks Bahr deserves to die in prison for his crime. “This was so violent and so premeditated. Other situations deserve a second chance but something as violent as this was — it was so angry and so violent and so cold.”

Hard-learned lesson

Dawn Romig has testified before the state legislature, trying to block efforts to end life sentences for underage felons. In her tidy brick home, she shares remembrances of her daughter, including a quilt made of Danni’s clothing.

–Jennifer Bishop Jenkins

“We have moved on, we’ve healed as much as I think we are going to heal, but we got to keep her memory alive,” Romig said. “She is still our child. Just because she is gone doesn’t mean that my kids don’t have a sister, that we don’t have a daughter. She’s still our child.”

She and her husband take a visitor to Danni’s grave site. They gently clean the marker and remove leaves, revealing the image of Tweety Bird, their daughter’s favorite character.

Romig plans to be at the Supreme Court for the two unrelated cases.

“I guess the only thing that came out of this horrible death of Danni is a lesson — a lesson that my children will have to learn the hard way. My son will respect girls and cherish them, never hurt them and never force them to do something they don’t want to do. And I need to try to teach my daughter some warning signs to look for so she can stay away from people” like Danni’s killer.

Edwin Desamour offers no excuses, but an explanation for why life on the streets turned him into a teenage killer and convict. In his role as mentor, he sees a measure of deja vu in his young charges.

“A lot of times I sit back and look at a lot of these kids out here and can’t believe that was me,” he said. “I can’t believe that was me walking down the street thinking, acting and talking like that. Wow. I can’t believe those stupid things.”

Desamour advocates for a fresh look at how police officers and courts deal with young offenders.

“Kids can turn their lives around. I turned my life around,” he said. “What’s at stake here are kids’ lives. We’re losing two lives. When a violent crime occurs, especially if it’s murder, not only does one person die, the other kid dies also. Prison is the cemetery of the living when a kid enters the system where it seems like there is no return once you get up in there.”

Clemency and LWOP for Under-18 Killers

Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, 2011

Twice in recent years Senator Yee has pushed failed legislation in Kruzan’s name to retroactively offer parole to some of the worst murderers in the state. Such blanket legislation would not only traumatize crime victims and ignore their constitutional rights, but also endangers the public and adds exorbitant expense to an already strained legal system.

The California legislature has wisely twice rejected Senator Yee’s bills attempting to abolish life sentences for rare and extremely heinous aggravated murders committed by 16 and 17 year olds (JLWOP “juvenile life without parole”) with broad opposition from law enforcement, victims, and other groups concerned with public safety.

The National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers (www.teenkillers.org) issued the following statement from prominent California Attorney and NOVJL President Daniel Horowitz: “Whether people agree or not with the underlying decision of the Governor about the merits of this killer’s clemency case, Kruzan’s case is Exhibit #1 why states should not enact legislation retroactively abolishing JLWOP sentences. JLWOP for juvenile killers is entirely appropriate, effective, and constitutional, and all states should have the sentence as an option—period. Most states already do. Executive grace (clemency) is a core, state constitutional power reserved to the governor. A Governor is directly accountable to the people for his decisions, good or bad. The system worked.”

Twice in recent years the United States Supreme Court has affirmed the constitutionality of JLWOP for murder cases, first in the Roper v Simmons decision in 2005, then in 2010’s Graham v Florida decision. A significant study on JLWOP nationally called Adult Time for Adult Crimesfound the rarely used sentence widely supported throughout the nation, used in several other nations, and legally effective and appropriate for the worst cases of juvenile killers.

Attorney Phyllis Loya, whose son Larry Lasater was a Pittsburg, California police officer murdered in the line of duty, said, “States have an obligation to protect its citizens from the worst of the worst, no matter what their age. And there are more than adequate protections for offenders in the system to make their case for what their appropriate sentence should be. Every offender has appeals, habeus corpus, and clemency opportunities. Juvenile offenders facing transfer to adult court in California have extra layers of hearings and legal protections in which to argue the appropriate disposition of their cases. Senator Yee’s bill is completely out of order and made even more obviously so by Governor Schwarzenegger’s decision. All juvenile killers in every state have the opportunity to have their sentences reviewed by the governor, and appellate courts.”

Charles Stimson, Senior Legal Fellow at the Heritage Foundation in Washington D.C. and the author of Adult Time for Adult Crimes said, “The Governor decided to give clemency to Sara Kruzan for reasons that are obvious, and this act alone does more to kill Yee’s proposal than all the other reasons to defeat this legislation. Despite the propaganda campaign by anti-incarceration activists in California, Yee’s problematic bill is simply not necessary.”

###

For detailed information on NOVJL, the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, and the facts of the crime stories of what happened to our loved ones at the hands of teen killers, see our website at www.teenkillers.org. NOVJL President Daniel Horowitz, nationally renowned defense attorney, is a frequent guest analyst on national news media, including CNN, MSNBC, Fox and other stations. His wife was murdered by a “juvenile lifer” in California.

Victims of victims: Juvenile lifers punish families with undeserved ‘life sentences’

Mlive, 2011

James and Kimberly Sorensen will never be released from their “life sentence.”

The Westland couple did nothing wrong but are forever entrapped in reliving what happened to their son Daniel Sorensen four years ago.

“Speaking from the point of a victim, this is a life sentence for everyone who was close to somebody who was murdered by a juvenile,” said Kimberly Sorensen, 51. “It isn’t just the hearings and the meeting you have to attend, it’s every time a birthday rolls around or a holiday, you relive it all over again.”

Daniel Sorensen, 26, was murdered and decapitated Nov. 7, 2007 by Jean Pierre Orlewicz, a then 17-year-old from Plymouth Township who was sentenced to life without parole in 2008.

During the trial, prosecutors called Sorensen’s slaying a “thrill kill.” They said Orlewicz, now 21, was excited by the prospect of killing someone and getting away with it.

Orlewicz’s attorney, James Thomas, said the teen stabbed and then beheaded Daniel Sorensen in self-defense after an extortion plan went wrong.

The jury found Orlewicz guilty after testimony from Alexander Letkemann, a Westland teen who Orlewicz recruited to help him dispose of the Daniel Sorensen’s body. Letkemann testified that Orlewicz laid out items — including latex gloves, garbage bags, bottles of Drano for the cleaning, knives for the killing, a hacksaw for the decapitation and a propane blowtorch to remove his fingerprints — in preparation for the murder in his grandfather’s garage.

According to James Sorensen, Letkemann’s willingness to testify is what helped put Orlewicz in prison, where he should remain for the rest of his life.

“Do I feel justified in assuming the stance that life without parole is right with somebody for that age? Absolutely,” he said, adding he is OK with Letkemann, now 22, only receiving 20 to 30 years in prison as part of a plea deal.

In Michigan, homicide suspects ages 14 to 17 automatically go to adult court. If convicted of first-degree murder, which includes participating in a crime where someone else does the killing, the only possible sentence is life without parole — unless a plea deal is reached.

However, the “agony” for families of victims doesn’t end with a sentencing. The Sorensens, as well as other families in Metro Detroit, have to deal with appeals and constant reminders of their loved ones’ deaths.

“When a jury comes back with a verdict, you have all types of people saying, ‘Oh, he was found guilty, he’s going to prison for life, that must give you closure,’ ” said James Sorensen, 55. “If they think there’s closure, they’re sadly mistaken.

“What we’ve had to deal with for the last four years with all the appeals hearings, everything that’s appeared in the papers every time this comes up, questions being asked, that’s difficult.”

In Michigan, 358 prisoners are serving mandatory life sentences for crimes committed between the ages 14 and 17, the second-highest number in the nation.

Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, says the future for families of victims murdered by juveniles in Michigan could become worse.

The American Civil Liberties Union is fighting to give juvenile lifers a second chance, through a federal lawsuit in Detroit.

“First thing, they (the ACLU) need to do is to stop filing retroactive legislation and holding a gun to the victims’ heads,” said Bishop-Jenkins, whose organization is made up of the families of murder victims killed by teenagers. “That’s what this legislation feels like to us.”

Bishop-Jenkins’ sister, Nancy Bishop-Langert, was shot to death along with her husband, Richard Langert, and their unborn child in suburban Chicago in 1990 by 16-year-old David Biro.

In 1991, a judge sentenced Biro to life in prison for the “cold-blooded killing.”

Bishop-Jenkins, who prefers not to speak Biro’s name, said there is a middle ground that can be reached to change legislation in Michigan, but the ACLU’s retroactive approach is the wrong way of doing so.

“Crime is very individualized,” she said. “Anything that gives more individual case by case discretion is going to be helpful.

“Now that being said, there are some people for whom life without parole is the right sentence.”

Bishop-Jenkins said judges in Michigan should have more options for sentencing juveniles, and maintain the life without parole for those, including her sister’s killer, who showed “utter disregard for human life.”

And Bishop-Jenkins’ feelings on the legislation are shared by other members of the organization, including Jody Robinson.

“I feel as long as the ACLU tries to do something retroactive and change the way things are, I will never have closure,” said Robinson, treasurer for the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers. “I will never again feel that I can have closure with this; every year it gets brought up and I have to relive it.”

Robinson’s brother, 28-year-old auto mechanic James Cotaling, was found stabbed to death in May 1990 in a house in Pontiac.

“Trying to just deal with it and put it to rest was hard enough without having legislators bring up possibly changing the sentence of the juvenile responsible,” said Robinson, of Oakland County. “It has been very difficult on everyone in my entire family for many reasons.

“We were given a life without parole sentence. We were promised we would never have to deal with this again and unfortunately, that’s not the case.”

Barbara Hernandez, a 16-year-old at the time of the killing, and her older boyfriend, James Roy Hyde, were convicted of murder and robbery charges. They were sentenced to life in prison, but Robinson continues to fight to keep them in prison.

“They claim these children deserve a second chance, and I always say to that, ‘Well, where’s my brother’s second chance?” said Robinson, a mother and youngest sibling of seven. “He doesn’t get a second chance to have a family, have children, start his own business like he dreamed of. He doesn’t get a second chance.”

Robinson, Bishop-Jenkins and James and Kimberly Sorensen said they will continue to speak out in honor of their loved ones who can no longer speak for themselves because of juvenile murderers.

“It’s possible to have peace, but it’s a life sentence,” said Kimberly Sorensen. “Your life is forever changed. There’s never that same level of joy you experienced before that person was taken away.”

Juvenile lifers may get out, but victims’ families don’t want a law to open the door

Mlive, 2011

After decades in prison, they may eventually come to terms with their crimes.

They may come to regret their actions or understand them or get past them.

But their victims won’t.

And to many loved ones of homicide victims killed during crimes by juveniles, keeping them in prison until the day they die is the only option.

“There are people on this planet who are utterly and deeply dangerous and dysfunctional, and we can’t fix everybody, and there are some people who we have to keep separated from the rest of us,” said Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

In Michigan, 358 prisoners are serving mandatory life sentences for crimes committed from ages 14 to 17, second in the nation.

The American Civil Liberties Union is fighting to give them a second chance, through a federal lawsuit in Detroit. The U.S. Supreme Court this week also said it would take up the issue.

Jody Robinson is fighting back.

“They claim these children deserve a second chance and I always say to that, ‘Well, where’s my brother’s second chance?’” said Robinson, of Oakland County, who is treasurer of the national group.

“He doesn’t get a second chance to have a family, have children, start his own business like he dreamed of. He doesn’t get a second chance.”

Her brother, James Cotaling, a 28-year-old auto mechanic, was killed inside a Pontiac house in 1990.

He suffered 25 knife wounds and was nearly decapitated.

Barbara Hernandez, then 16, and her 20-year-old boyfriend, James Roy Hyde, were convicted of luring Cotaling into the house, killing him and stealing his car.

“We were given a life without parole sentence. We were promised we would never have to deal with this again, and unfortunately that’s not the case,” Robinson said.

Hernandez was denied clemency by Gov. Jennifer Granholm in 2010. Still, the issue resurfaces regularly in legislative bills, so far unsuccessfully.

“After 10 years, I got to a place where I could accept it and I could remember my brother’s smile,” Robinson said. “I remembered the fun times we had and I didn’t think so much of how he died or the brutality of it.”

Robinson said she gained a measure of peace until the legislation surfaced for the first time. She testified against the bill in Lansing, and she said that summoned up all the horror she lived through after Cotaling’s death.

“I’ve had to do that every year since and it has brought back nightmares,” said Robinson, who is 39 and lives in Davisburg.

“The first year I had night terrors. My children didn’t understand why I had to sleep with the light on.”

Would it be a punishing change?

The ACLU’s pending federal lawsuit argues life sentences for juvenile offenders are cruel and unusual punishment. It charges they have a lesser-developed character than adults, live longer in prison, and have a greater capacity for reform.

The lawsuit seeks parole reviews when the inmates reach 21, then every five years after.

Deborah Labelle, the lead attorney representing the ACLU, said she sympathizes with victims’ loved ones and the deep hurt they feel.

“You have a right to every feeling you have, certainly, and I would never try to persuade you to be different,” she said.

“That’s why we don’t have vigilante justice. The state and the prosecutorial role and the legislative role are all certainly different than the role of the victims’ family which may be to say, ‘You know what, I would like the death penalty.’ But we don’t have that in this state.”

Bishop-Jenkins, however, said it would be cruel and unusual punishment for victims’ families to continually face the possible release of the killers.

“Don’t torture victims families by making all of them go to parole hearings every five years for the rest of their lives,” she said. “That’s horrible.”

She scoffed at the idea life without parole would constitute cruel punishment for an offender just under 18, but not for a convict just turned 18.

“They’re trying to argue that the mere age of the offender makes the no-parole option equivalent to torture, and I just don’t see it,” she said. “I do know that when my sister was murdered, she was tortured.”

Bishop-Jenkins’ pregnant 25-year-old sister and her 28-year-old brother-in-law were shot to death inside their Chicago home by a 16-year-old in 1990.

“The man that killed her, who was four weeks shy of the adult criminal age in Illinois, who is now serving three life sentences, he is not being tortured,” she said.

“He gets to see his parents every week. … He’s got to go to school. He gets medical care. He gets exercise. … He gets to laugh. He gets to cry. He gets to worship. He gets to feel pleasure. … He gets to grow. He gets to learn. He gets to reflect.”

Some room for variation?

But Bishop-Jenkins does agree Michigan law allows too few options for sentencing juveniles in homicide cases.

“Our organization’s position is that age is not a factor as much as is the culpability of the individual offender,” she said. “We actually think that there should be a lot of case-by-case variance in court.”

In Michigan, homicide suspects ages 14 to 17 automatically go to adult court. If convicted of first-degree murder — which includes participating in a crime where someone else did the killing — the only possible sentence is life without parole in adult prison.

Patrick McLemore is doing that sentence for the killing of 67-year-old Burton community activist Oscar Manning during a 1999 home invasion.

He was 16. His 19-year-old partner was sentenced to 37 1/2 years to 50 years after pleading no contest to a lesser murder charge. McLemore maintains his only role was as a lookout.

His mother, Patricia McLemore of Burton, holds out hope she will someday see her son outside the walls of Kinross Correctional Facility in the Upper Peninsula. But she still thinks about the victim’s family.

“I try to put myself in the victim’s place,” said Patricia McLemore, 64. “I have wanted since it first happened to go to them and tell them how sorry I was that that happened. But my pastor told me, ‘No, you’re the last one they want to see.’ It still hurts and I do still think of them.”

She’s counting on the ACLU lawsuit to someday give her son a shot at parole.

But Manning’s family will do anything to keep him behind bars.

“You don’t have blood on your shoes when you’re just a lookout,” said Sue McFall, the victim’s daughter, referring to expert testimony during McLemore’s trial.

Neighborhood youths also testified McLemore told them he and Reid beat Manning with a wrench, according to Flint Journal files.

“All I know is that he needs to stay in there,” said McFall, 61, of Burton. “My family is going to have to fight to keep him in there.”

Robinson and Bishop-Jenkins oppose any comprehensive legislative or judicial measures that would have retroactive effect.

“If there’s a handful of them that should get out, then let’s find out who those are and let’s give them clemency,” Bishop-Jenkins said. “That’s what the governor’s for. If there are some that got over-sentenced, then fix it. Fix it through appeals, fix it though habeas, fix it through sentencing hearings. Fix it through gubernatorial clemency.”

Parole hearings every five years, Robinson agrees, would be torture.

“If they grant this, then every five years I have to go to a parole hearing because every five years she would be eligible,” she said of the teen convicted in her brother’s slaying, now a 37-year-old inmate at the Huron Valley Correctional Facility in Washtenaw County.

“So then I am definitely sentenced to a life sentence of reliving my brothers horror. And how is that fair to the innocent victims?”

Cases question life in prison sentences for juvenile crimes

StarNewsOnline, 2012

There is Peter Saunders, who, at the age of 16 stabbed and bludgeoned to death an elderly woman in her Chicago home. Years after the murder landed him in prison, he mailed a federal judge a letter that threatened to “put a nine millimeter slug right in your head.”

Then there is Kevin Boyd, who as a 16-year-old Michigan boy gave his mother keys to his father’s house knowing that she was headed there to kill him. Since being convicted for his role in the murder, Boyd earned his GED, several trade certificates and, according to court documents, is considered a model inmate.

Stories like those have come to personify opposing sides in a swirling debate over the issue of juvenile justice as the U.S. Supreme Court heads into this week preparing to decide whether sentencing teenagers to life imprisonment violates the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

On Tuesday, the justices are expected to begin hearing arguments in two cases whose outcome could reshape criminal law and give inmates once consigned to die behind bars a shot at getting out.

The Supreme Court ruling could reverberate across the country, bringing about change in 43 states, including North Carolina, where convicted juveniles can be locked up for life.

North Carolina is a particularly unique situation because it is one of two states that classifies 16-year-olds as adults in the eyes of the court; other states define adulthood as over 18.

Experts say the court’s determination could become ammunition for those wanting reforms in North Carolina law.

“I can imagine, depending on how the case comes out, there could be language helpful to those wanting to change the juvenile age in North Carolina,” said James Markham, assistant professor of public law and government at the UNC School of Government.

The upcoming decision has prompted a spirited discussion about federalism, victims’ rights, criminal justice reform and the culpability of young killers.

Over the past several years, the Supreme Court has been steadily chipping away at severe sentences, especially when it comes to teenage offenders.

In 2005, it banned the death penalty for juveniles. And two years ago, it made a landmark ruling in Graham v. Florida that courts may only impose life sentences on juveniles convicted of murder.

Now, the court will consider two cases involving 14-year-olds, with human rights advocates urging justices to extend the Graham decision to give young murderers sentenced to spend the rest of their days in a prison cell a chance at release.

One case involves Evan Miller, who was convicted in Alabama for a 2003 murder in which he and an older youth beat his 52-year-old neighbor with a baseball bat and then set the victim’s house ablaze. The three had spent the evening smoking marijuana and playing drinking games when the altercation ensued. The neighbor died of smoke inhalation.

The second concerns Kuntrell Jackson, an Arkansas prisoner who joined two older boys in robbing a local video store in 1999. After demanding money from the clerk several times, one of the other boys fatally shot her with a shotgun.

How many inmates the Supreme Court decision will ultimately affect varies by opinion. The American Civil Liberties Union estimates there are 2,570 prisoners who were sentenced to life without parole as adolescents, including 44 in North Carolina.

Others have denounced that statistic as exaggerated and manufactured. Charles Stimson, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation and co-author of “Adult Time for Adult Crimes,” said the actual figure is probably around 1,300 nationwide, but could be slightly higher because some states have failed to keep accurate records.

Much of the debate centers on the degree to which juveniles should be held accountable for their crimes and the extent their behavior is molded by environmental factors outside their control.

Advocates of repealing life without parole policies for young offenders have been buoyed in recent years by a throng of research they say proves adolescents are psychologically and biologically underdeveloped, and are therefore prone to rash decision-making and more likely to conform to social pressures. But more importantly, they argue, juveniles are retrievable and capable of recasting their identities.

“That branch of science has made incredible strides in the last decade and a half with the result being that we now have a large body of well-respected scientific evidence,” said Robin Walker Sterling, an assistant professor at the University of Denver and a former special counsel at the National Juvenile Defender Center.

Research often cited by opponents of juvenile life sentences was conducted by Dr. Laurence Steinberg, a psychology professor at Temple University, and his colleagues. He said that their work has shown “pretty conclusively” that as a group, adolescents are more short-sighted, impulsive and susceptible to pressure than adults.

“The brain system responsible for people engaging in risk-taking, sensation-seeking and reckless behavior are much more easily aroused during adolescence than they are during adulthood,” he added. “And that is especially true between the ages of 10 and 16.”

Victims’ rights groups and other justice expects have filed briefs with the Supreme Court urging it not to strip states of their right to give juveniles life punishments, arguing that even young people can distinguish right from wrong and are well-aware of the consequences of their actions.

Jennifer Bishop Jenkins, president of a Michigan-based victims’ rights group called the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, said the national discourse largely excludes victims who live everyday with the lingering thought of how their loved ones died.

“What they’re proposing is retroactively undoing life without parole sentences. These victims’ families have been through hell,” she said. “If anybody is a human rights advocate, they should care about the victims’ rights as well.”

In 1990, Jenkins’ sister and brother-in-law and their unborn child were murdered by a 17-year-old who was later sentenced to life without parole. Jenkins said forcing already traumatized families to relive the events of the murder by appearing before a parole hearing.

“There’s this huge advocacy movement by people that claim to be human rights advocates and yet they are willing to torture victims’ families by reopening cases that are years old and make them go back to court and the parole board for the rest of their lives,” Jenkins said.

Should Juveniles Receive Life Sentences Without Parole?

NewsOneStaff, 2012

Opponents say that murderers sentenced to life without parole, no matter how young, do not deserve the chance to be free. Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins is among those opponents. She worked hard to end the death penalty in Illinois but parts company with fellow criminal justice reform advocates on this issue, in large part because it will force the families of victims to again confront tragedies when inmates apply for release.

Her opposition is based in personal experience. Her pregnant sister and her brother-in-law were murdered in April 1990 when 16-year-old David Biro forced them into the basement of their Winnetka, Ill., home and shot them to death as they pleaded for their lives, a horrific crime discovered by her father. Biro is serving a life without parole sentence.

“It is an utter violation of due process for them to say that a finalized case, a finalized sentence, that they would reopen that,” said Bishop-Jenkins, who is president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers and director of Illinoisvictims.org. “We never get to be free of this guy. He gets a shot at release, but my family never gets freedom from this. This will change everything for victim’s families.”

Bishop-Jenkins said she does not oppose some change in new cases _ although she believes that judges should have the flexibility to impose a life-without-parole sentence in the most heinous cases. But it is the old cases in which witnesses have died or evidence can no longer be found that she said are the most troubling. That, she said, will make it more difficult for the families of victims to mount opposition when an inmate comes up for parole.

“It’s the bait-and-switch that’s so torturous,” she said. “We walked away from that case 21 years ago believing it was over.”

Supreme Court to take up life terms for young killers

Mon., March 19, 2012

Steve Mills

Chicago Tribune

‘Violation of due process’

Opponents say that murderers sentenced to life without parole, no matter how young, do not deserve the chance to be free. Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins is among those opponents. She worked hard to end the death penalty in Illinois but parts company with fellow criminal justice reform advocates on this issue, in large part because it will force the families of victims to again confront tragedies when inmates apply for release.

Her opposition is based in personal experience. Her pregnant sister and her brother-in-law were murdered in April 1990 when 16-year-old David Biro forced them into the basement of their Winnetka, Ill., home and shot them to death as they pleaded for their lives, a horrific crime discovered by her father. Biro is serving a life without parole sentence.

“It is an utter violation of due process for them to say that a finalized case, a finalized sentence, that they would reopen that,” said Bishop-Jenkins, who is president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers and director of Illinoisvictims.org. “We never get to be free of this guy. He gets a shot at release, but my family never gets freedom from this. This will change everything for victims’ families.”

Before he went to jail, Larod Styles, like Adolfo Davis, had gotten into some trouble – but nothing approaching what happened when Styles was 16. That was when he and three others were charged with the December 1995 murders of two men gunned down in an auto sales office on the city’s South Side during a robbery. Because he was 16, he was automatically tried as an adult. Although someone else was the alleged triggerman, Styles was still convicted of murder. Because two people were killed, he was subject to a mandatory sentence of life without parole.

Weighing new hope for young killers

By Steve Mills

Posted Mar 19, 2012

CONSIDERING VICTIMS

Opponents say that murderers sentenced to life without parole, no matter how young, do not deserve the chance to be free. Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins is among those opponents. She worked hard to end the death penalty in Illinois but parts company with fellow criminal justice reform advocates on this issue, in large part because it will force the families of victims to again confront tragedies when inmates apply for release.

Her opposition is based on personal experience. Her pregnant sister and her brother-in-law were murdered in April 1990 when 16-year-old David Biro forced them into the basement of their Winnetka, Ill., home and shot them to death as they pleaded for their lives, a horrific crime discovered by her father. Biro is serving a life without parole sentence.

“It is an utter violation of due process for them to say that a finalized case, a finalized sentence, that they would reopen that,” said Bishop-Jenkins, who is president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers and director of Illinoisvictims.org. “We never get to be free of this guy. He gets a shot at release, but my family never gets freedom from this. This will change everything for victim’s families.”

Families of murder victims criticize report about juveniles serving life sentences

- ANN ZANIEWSKI

May 27, 2012

Some families of murder victims are criticizing a report that advocates ending the practice of sentencing young offenders to life in prison without parole.

Jody Robinson Cotaling of Davisburg said the report, “Basic Decency: Protecting the human rights of children,” is flawed, beginning with its name.

“They named it, ‘Basic Decency,’ ” she said. “To us, that is just very demeaning to victims. … We find the use of that very offensive.”

The report recently was released in partnership with the ACLU of Michigan and an advocacy group called Second Chances 4 Youth. It makes a number of recommendations, including abolishing sentences of life without parole for people who commit homicides before they turn 18 and requiring judges to consider a young person’s immaturity, lack of experience and other factors in issuing sentences in such cases.

According to the report, Michigan has the second-highest number of people serving lifetime prison sentences for offenses that occurred before they turned 18.

Members of National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers are

critical of the “Basic Decency” report and say they’re working on a page-by-page analysis that will be posted on their website, www.teenkillers.org.

Robinson Cotaling, who is secretary of the group’s Michigan chapter, said the report was filled with “half-truths” and didn’t tell the whole story.

Attorney Deborah LaBelle, principal author of the report and director of the Juvenile Life Without Parole Initiative, stands behind the document.

“The report relied upon objective data obtained from the Michigan Department of Corrections, documented peer review research, the (U.S.) Supreme Court decisions and findings in Graham (v. Florida), and a great deal of records and transcripts,” LaBelle said.

Robinson Cotaling said the section in the report about “brain science” was misrepresented. The report said the brain’s frontal lobe, which is associated with impulse control and understanding consequences, is underdeveloped in adolescents compared with adults. Scientific research has shown that the part of the brain that allows for mature decision-making is not fully developed in teenagers, according to the report.

“We don’t dispute that the frontal lobe grows in capacity into (a person’s) late 20s,” Robinson Cotaling said. “There’s nothing in the brain science that diminishes criminal culpability.”

The report says that to date, 376 young people have been sentenced in Michigan to life without parole.

“Regarding the number of 376 offenders — we demand the list of names,” reads a page on NOVJL’s website that criticizes the report. “First, we know that this includes all the 17-year-old convicted murderers serving life. This report labels them juveniles but under Michigan law (and many other states) 17 is adult age.”

NOVJL’s website says the report’s claim that the U.S. is the only nation in the world to sentence teen killers to life in prison isn’t true, and that the report contains flawed references to court rulings.

LaBelle said the United Nations, Amnesty International and various other sources have recognized that the U.S. is the only country that has such a sentence for youth younger than age 18.

LaBelle said young people who commit serious crimes need to face significant punishment, but there should be a recognition that they are different than adults. She noted that people cannot vote, join the military or get married without parental consent until they turn 18.

“We know that they’re not mature,” LaBelle said when the report was first released. “When they do mature, they’re not always what they were, and they should be given a second chance.”

LaBelle said a main concern is that adults often end up serving less time than juveniles for comparable crimes due to plea bargaining.

The average length of prison time served by an adult who took a plea offer for a first-degree homicide charge was 12.2 years, according to the report. Juveniles are at a disadvantage in negotiating and understanding plea offers because of their immaturity, and they often reject plea offers at a higher rate than adults, the report said.

In Michigan, a conviction of first-degree murder carries a mandatory sentence of life in prison without parole. A conviction of armed robbery or other serious crime that is categorized as a capital offense carries a maximum penalty of life or any term of years in prison.

Prosecutors have the discretion to charge people ages 14 and older as adults in cases involving serious crimes. If someone 14 or older is convicted of first-degree murder, a judge must sentence that person to life in prison without parole if the defendant was charged as an adult.

If someone younger than 14 is charged with a capital offense, the prosecutor can still designate him or her as an adult, but the judge has discretion in sentencing and can sentence that person as a juvenile or an adult, or issue a blended sentence.

Robinson Cotaling’s involvement in the issues surrounding juvenile life without parole sentences grew out of the death of her brother, 28-year-old auto mechanic James Cotaling.

James Cotaling was found stabbed to death in May 1990 in a house in Pontiac. Barbara Hernandez, who was 16 at the time of the killing, and her older boyfriend, James Roy Hyde, were convicted of murder and robbery charges.

They were sentenced to life in prison.

Robinson Cotaling and other members of her family believe Hernandez, who was reported to have posed as a prostitute to lure James Cotaling to the house, was directly involved in the killing. They believe she should stay behind bars for the rest of her life.

Officials with the Michigan Women’s Justice & Clemency Project have filed petitions for clemency on behalf of Hernandez. Carol Jacobsen, director of the Justice & Clemency Project, told The Oakland Press in 2010 that Hernandez had an abusive home life and Hyde preyed upon her. She said Hyde, not Hernandez, was the killer.

When a hearing was held in 2010 on Hernandez’s petition for commutation, James Cotaling’s family urged members of the Michigan Parole and Commutation Board not to consider her for release.

They were thrilled when they got a letter saying that Hernandez had not been granted clemency.

Robinson Cotaling said that while sentences of life without parole might not be an appropriate sentence in every case involving a teenager who killed someone, it should remain an option.

“I will not ever say that the juvenile justice system does not have flaws, and we’re not saying that every single teen killer deserves life without parole,” Robinson Cotaling said.

“We’re saying it needs to stay on the table for the worst of the worst.”

https://www.dailytribune.com/news/families-of-murder-victims-criticize-report-about-juveniles-serving-life/article_48e772fd-c9e4-5859-a69c-73f9f51700a5.html

Remember the Victims of Juvenile Offenders

Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins is the president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

JUNE 5, 2012

When my pregnant 25-year-old sister and her husband were murdered by a 16-year-old, she left a last inspiring message of love in her own blood that transformed my life. The teenager who killed my sister’s family was born of privilege in the Chicago suburbs. He planned the crime for weeks and executed it alone. He had committed crimes before, but never faced serious consequences. His parents always bailed him out, never wanting him to get in real trouble. If only he had gotten in trouble the first time that he shot out people’s car windows with his BB rifle, or when he was accused of setting that girl’s sweater on fire in school, or any of his other serious early crimes. But he never faced legal consequences, so he kept going because, he told his friends, it gave him a “rush.”

Consequences are good, especially for early crimes. That’s when punishment can help young people change and grow.

Most young people who commit crimes appropriately stay in the juvenile justice system which is focused on rehabilitation. But there are rare cases when older teens demonstrate heinousness and culpability and carry out truly horrific crimes. For those few a couple years of detention and programs are not enough. These individuals can be appropriately tried as adults. They need to grow older before release. They need long term evaluation to see if they will ever be able to rejoin society. And we should not rule out a sentence of life without parole in extreme cases. We must balance the victims’ families’ right to some legal finality with the likelihood that the offender will ever qualify for release. It’s a sad fact that some sociopaths start young and remain dangerous all their lives.

As a volunteer with the Cook County juvenile probation program for more than a decade sharing my sister’s story with youthful offenders, I am always emotional when I talk to them about how their getting in trouble is a good thing. It means they get a chance to learn from their mistakes. Consequences are good. They help young people change and grow. They have been given a chance that I’d give anything for my sister’s killer to have had before his crimes escalated. It always inspires me how many young people actually get this.

Cases vary widely and so all must be judged individually. Sentencing has to focus not only on the offender but also on public safety and prevention of further victimization. Our society is appropriately concerned, as this forum demonstrates, with helping juveniles. Let’s also remember that the victims of violent juvenile crime need just as much of our support.

Victims’ Rights and Restorative Justice: Is There a Common Ground?

JJIE, 2012

Last week my column on the resentencing of juveniles who had received life without parole drew a comment from the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers (NOVJL). The commenter had a legal argument in opposition to my own view, but more striking, at least to me, was the sentence that asked how I am going to, “support, inform, and not re-traumatize the devastated victims’ families left behind in these horrible crimes.”

I continue to reflect on that comment, and to ponder indeed how I am going to accomplish these goals. In moments of doubt I wonder if they are indeed incompatible. The way in which policies are changed is often adversarial, and such positioning can lend itself to demonization, even the demonization of victims of crime. This goes beyond civility, as important as it may be, to what values we as a society want to embody. I want to help create a society that cares for the needs of everyone affected by crime, most importantly of all the victims and their loved ones. If those needs are ignored then justice is not done.

Many members of NOVJL are in support of Restorative Justice, and their website points out many areas of policy where advocates of both juvenile offenders and victims can come together in agreement. Jennifer Bishop, the leader of the group, in an interview with Youth Radio, said that restorative justice isn’t applicable in cases of murder, since the victim cannot be restored, but also went on to say, “There’s another term — transformative justice — that seeks to transform the experience for both offender and victim. I’m a strong supporter of that.” This approach is about finding ways to transform what has happened, and is not dependent on the offender’s release.

I am heartened by these signs that there is indeed some common ground between those who support victims and those seeking juvenile justice reform. I intend to keep these considerations in mind in my own attempts to bring restorative justice to my community, and to encourage others to do the same.

National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers: Supreme Court ruling comes against ‘backdrop of tragedy’

Jun 25, 2012

Brandon Howell

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s striking down of life-without-parole sentences for juveniles, an organization advocating for the victims of such offenders seeks to turn attention to survivors.

The National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers (NOVJL) issued a news release Monday afternoon, calling for support for the families and friends of victims slain by juvenile lifers.

“This ruling invalidating the life sentences of many of our family members’ murder cases comes against the backdrop of tragedy,” NOVJL President Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins said in a statement. “While we understand the tragic consequences to the killers, the entire context of this decision is first and foremost the appalling and senseless murders of our innocent loved ones and the devastation left behind.

“Everyone’s biggest concern now must be finding, notifying and supporting the many affected victims’ families.”

Michigan is second in the nation in the number of inmates serving life for crimes committed at 17 and younger, 358. All of them will be resentenced following Monday’s ruling from the highest court in the land, which came by a 5-4 margin.

The NOVJL

raised concerns voiced earlier Monday by its secretary, Jody Robinson

, an Oakland County woman whose brother was killed by a juvenile lifer in 1990. Robinson suggested resentencing Michigan’s juvenile lifers will open old wounds for victims’ loved ones.

“Victims’ family members whose cases have been reopened by this decision will need resources devoted to supporting them through this process,” Bobbi Jamriska, of NOVJL Pennsylvania, said in a statement. “We call on everyone involved to gather all stakeholders to devise a system that can best serve not only the offenders, but also victims and the public.”

Bishop-Jenkins asked for the cooperation of all in overseeing the implementation of better reforms to the criminal justice system.

“NOVJL wants to work with all parties to see that reforms are ultimately enacted in ways that protect everyone,” she said. “We urge the juvenile advocates who have spent millions in recent years advocating for this re-opening of their sentences to now devote their resources to the much needed victim support.”

The NOVJL submitted an amicus brief, a document written by a third party volunteering information for a ruling, to the Supreme Court as it deliberated the juvenile lifer case.

High Court Bars Mandatory Life Terms For Juveniles

June 25, 2012

Dissenting Opinions

“There’s going to be a deluge of legislation and litigation and re-sentencing now that’s been opened today by the court, and most victims’ families don’t even know that this has happened,” predicts Jennifer Bishop Jenkins, who leads the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Steven Breyer and Sonya Sotomayor joined the majority opinion. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito all filed their own dissents, each of which was joined by Justice Scalia.

Justice Alito announced his dissent orally from the bench, a rare move used to signal a justice’s particular disapproval of a decision. Alito took issue with the majority’s use of the word “children” throughout its opinion, and in his opinion, he referred to the defendants only as “murderers.” From the bench, he disparaged the justices in the majority for basing their decision on their own personal preference, and said their opinion ignores reality. “The decision in this case is based on a vision of a different society, an elite vision of a more evolved, more mature society,” he said, mocking the majority’s invocation of the “evolving standards of decency” that undergird the Eighth Amendment.

“What the majority is saying is that members of society must be exposed to the risk that these convicted murderers, if released from custody, will murder again,” he said, adding that the Supreme Court “has no license to impose our vision of the future on 300 million of our fellow citizens.”

9 to appeal sentences as juveniles

BRIAN BOWLING AND ADAM BRANDOLPH | July 10, 2012

Victims’ families said they’re angry at the decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, which said mandatory life sentences for juveniles constitute “cruel and unusual punishments.”

“The problem is they said this would never happen,” said Bobbi Jamriska, 41, of Shaler, vice president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, whose pregnant sister, Kristina Grill, 15, was killed in 1993 by Maurice Bailey, then 16, who also is appealing his sentence. “They’ve convinced all these murderers that they have a shot to get out of jail, but that’s a false sense. (Bailey’s) family is probably ecstatic, but the reality is those sentences were issued for a reason.”

How the decision will play out across Pennsylvania remains unclear. The high court did not issue guidelines to the states; spokesmen for the state parole board and Gov. Tom Corbett declined to comment, saying their offices are reviewing the decision.

“Right now they’re going to proceed like any other appeals hearing and we’ll have to figure out as it goes what’s going on,” said Mike Manko, spokesman for Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr.

Janet Price, 60, of Braddock did not want to talk about Ricardo Peoples’ application for release.

Peoples, 32, was 17 in May 1997 when he fatally shot Orlando Price, 22, and his girlfriend, Dionda Morant, also 22, in their Braddock apartment.

“The whole thing was a trauma and I cannot talk about it,” Price said. “I don’t care what he does. Orlando’s dead and this can’t bring him back.”

The state Department of Corrections estimates there are at least 373 people in Pennsylvania, including 55 from Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Fayette, Washington and Westmoreland counties, who could appeal their sentence. Juvenile justice groups puts the number at about 480.

State Sen. Stewart Greenleaf, R-Montgomery County and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, scheduled a public hearing on Thursday in Harrisburg to discuss what lawmakers need to do in the wake of the ruling. He hopes to have a bill in the Senate by September outlining how the appeals process would work. Jamriska will be testifying.

“There’s really nothing good about this from a victim’s perspective,” she said. “It pretty much flies in the face of what the victims were promised from the justice system.”

Jamriska said Bailey received an appropriate sentence. “He’s been in jail for 18 years. That’s how old my (sister’s baby) would be had he not been murdered,” she said.

The Uncertain Fate of Pennsylvania’s Juvenile Lifers

Liliana Segura and Matt Stroud

AUGUST 7, 2012

People listen to Bridge. He is perhaps the foremost Pennsylvania attorney addressing sentencing reform for violent juvenile offenders. “To shorten my statements, I could just say, ‘Whatever Brad Bridge says, I agree with,’ ” joked Andy Hoover, legislative director for the Pennsylvania chapter of the ACLU. This could prove important when it comes to one issue that dominated the hearing: the question of retroactivity. Should the Supreme Court decision in Miller necessarily apply to prisoners already serving juvenile life without parole?

Arguing that it should not was Bobbi Jamriska, who testified on behalf of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers. In 1993 a 16-year-old beat, stabbed and killed Jamriska’s pregnant sister. The perpetrator was sentenced to life without parole. A victims’ rights advocate ever since—and one of the most outspoken victim’s rights advocates in the state—Jamriska testified that because of a juvenile lifer her “whole life is in complete upheaval.”

“The sentences in these cases, cases like my sister’s murder, were prosecuted and sentenced under laws that were acceptable at the time,” she argued. Carol Lavery, another victims’ advocate, testified after her. “At some point in [their] journey, [victims] were assured that the offender who took the life of their loved one would spend the rest of his or her life in prison,” she said.

…

But sober legal explanations don’t persuade everyone. Nor do they necessarily lead to sound sentencing policy. As in other states, victims’ advocates in Pennsylvania often have a very strong voice when it comes to violent crime, and the push is toward harsh punishment. As Bruce Beemer, chief of staff at Pennsylvania’s office of the attorney general, argued, the Miller solution must provide “victims and their families some measure of justice, seeing that murderers are held appropriately accountable for the crime they committed and the devastation they caused.”

It’s up to the Senate Judiciary Committee to weigh all sides and come up with a legislative sentencing solution, ideally before October, when lawmakers break for the election. (In the meantime, the state Supreme Court has already scheduled oral arguments in two cases, to take place next month, which will set the tone for the resentencing of hundreds of prisoners.) It will be a challenge; while a number of different reforms were proposed, no consensus emerged as to how long teenage offenders should spend behind bars for violent crimes. Joe Heckel, of the advocacy group Fight for Lifers West, and William M. DiMascio, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, argued that they should receive sentences of ten years to life. (DiMascio suggested holding annual parole hearings once the ten-year minimum has been met.) Beemer would prefer a minimum sentence of forty years to life. And Bridge, citing occasions when Pennsylvania courts struck down the state’s death penalty statute and commuted prisoners’ sentences to “the next most severe” punishment available, suggested a similar route, converting life without parole sentences handed out for first- and second-degree murder to sentences of twenty to forty years, as in third-degree murder cases.

Kids Shouldn’t Die in Prison

AUGUST 10, 2012

Kimberlee Johnson

Impact and implications of ruling

Opponents of the abolition of mandatory JLWOP argue that given the heinous and sometimes premeditated murders that are committed, JLWOP should continue in the United States. It is important to remember that to the same extent that juvenile lifers, family members of these lifers, and fair sentencing advocates feel excited, victorious, and relieved, victims’ families, prosecutors, and victim-advocacy groups feel angry, defeated, and grieved.

These voices must also be heard. Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, said, “This ruling invalidating the life sentences of many of our family members’ murder cases comes against the backdrop of tragedy. While we understand the tragic consequences to the killers, the entire context of this decision is first and foremost the appalling and senseless murders of our innocent loved ones and the devastation left behind…

For families of victims of juvenile murderers, ruling reopens ‘traumatic wounds’

25 Sep 2012 US NEWS on NBC.com

25 Sep 2012 US NEWS on NBC.comKristina Grill, 15, was murdered in 1993 by her ex-boyfriend, who was also 15 at the time of her death and 16 when he was convicted. She’s seen in this file photo in Pennsylvania a year before her murder.

Nineteen years ago, Bobbi Jamriska’s younger sister was found murdered in a Pennsylvania schoolyard. As Jamriska grieved, one thing brought her solace: When a court found her sister’s 16-year-old ex-boyfriend guilty and sentenced him to life in prison without parole.

“When you get up every day, you think about what happened, but at least you know that there was that one constant, that life-without-parole was going to make sure that you never had to relive that part of it,” said Jamriska, 40, who lives in Pittsburgh.

But three months ago, the Supreme Court struck down mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles as cruel and unusual punishment. While the June 25 ruling wasn’t necessarily designed to be applied retroactively, some youth advocates are trying to use it to free so-called “juvenile lifers,” setting off a series of battles over what to do with the approximately 2,100 convicted murderers who were handed mandatory life-without-parole sentences for acts committed as youths.

For victims’ families, the decision has had huge emotional, and in some cases, legal implications.

“After the [Supreme Court] ruling, everyone felt like they were reliving the trial phase and their loved ones’ murder,” said Jamriska, who traveled to Washington, D.C., with other victims’ families to protest the ruling.

She is part of a support group called the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers.

“There were a lot of families who didn’t have any idea that this was even possible,” she said. “For them, it was literally one day business as usual, and then the next day, on the news, their whole world got turned upside down.”

Pennsylvania, where Jamriska lives, has the biggest concentration of juveniles serving mandatory life sentences — about 480 of them, the oldest of whom was convicted almost 60 years ago and is now in his 70s, according to the Juvenile Law Center. Earlier this month, the state Supreme Court in Pennsylvania began hearing arguments for why some of the lifers there should be paroled, including the ex-boyfriend who killed Jamriska’s sister in 1993.

No one in the legal system told Jamriska that the parole arguments involved her sister’s killer. She found out from a reporter’s voicemail about three weeks after the Supreme Court ruling that lawyers were trying to get parole for him.

Jamriska was stunned, but she said a lack of communication is somewhat understandable.

Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins / teenkillers.org

Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins / teenkillers.org

Bobbi Jamriska, of Pennsylvania, right, and Jody Robinson, left, of Michigan, another member of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, are seen advocating for victims’ families’ rights on March 20, 2012, outside of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., as the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether mandatory life without parole was cruel and unusual punishment for convicted juvenile murderers.

“There never was a contingency for if this person who was sent to life in prison with no parole is suddenly able to get out,” she said. “The DA’s office isn’t really staffed to manage that influx of appeals and those victims who are trying to get information — I don’t blame them.”

The state Supreme Court has put the arguments on hold and didn’t give a timeline for a ruling. The Pennsylvania legislature still needs to come up with an appropriate alternative punishment for minors going forward.

“The sentencing scheme in Pennsylvania currently provides that for any individual, juvenile or adult, convicted of first or second-degree homicide must either receive a sentence of death or a sentence of life without parole. For juveniles, that mandatory sentence of life without parole has been declared unconstitutional,” Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel at the Juvenile Law Center, said. “We think the courts should look to the next most severe sentence that is statutorily available in the state. Here, that means a sentence for third-degree murder, where you have a maximum sentence of 40 years.”

Levick suspects lawyers in other states will argue for that too. Since the Supreme Court ruling, North Carolina has passed a law replacing the mandatory life without prison sentence with a 25 years to life sentence; California’s governor is currently evaluating a law that sets up two different schemes where parole eligibility comes in at either 15 or 25 years to life, Levick said. In all, 28 states still allow mandatory life-without-parole sentences for minors, a situation that will have to change.

“States can still impose life without parole,” she said. “They just can’t make it the only sentence available.”

As some juvenile advocates try to undo sentences that have already been imposed, Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, 54, president of the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, worries about the families of their victims.

“Whenever you reopen traumatic wounds or you’re triggering a retraumatization, you’re talking about something that is going to affect people’s work, their sleep, their health, their marriages — everything,” she said.

Victims can only rely on each other for support, Jenkins said.

14 years old: Too young for life in prison?

“They don’t register for victim notification and they don’t monitor what’s happening, and then you get these reactions like what we’ve been getting in our organization,” Bishop-Jenkins said. “We’ve been trying very hard to find people to let them know that this multi-billion dollar campaign to free their loved ones’ killers is going on and they’re just shocked.”

Family photo/Courtesy of Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins

Family photo/Courtesy of Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins

From left to right: Richard Langert and Nancy Bishop Langert are seen on their wedding day in 1987 in Kenilworth, Ill., with Nancy’s parents and sister, Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins, far right. The Langerts were murdered by a 16-year-old in 1990.

There are potential legal issues too: Bishop-Jenkins’ pregnant sister and brother-in-law were murdered in their home in Winnetka, Ill., 22 years ago. It was Bishop-Jenkins’ father who found their bodies; his testimony served as crucial evidence in the initial trial. Eight years ago, her father died of cancer. She says the judge from the first trial has also died.

“My father was the best eyewitness to the carnage of the crime scene. We didn’t videotape him talking about the crime,” Bishop-Jenkins said. “We didn’t get the transcript of what the judge said at the sentencing hearing where he gave this speech about if anybody deserved life without parole, he did.”

She now fears she and her mom, 83, could have to face her sister’s killer in sentencing hearings in court. And while she doubts he will be granted parole, she said she worries lawyers may try again every couple of years.

Juvenile Killers and Life Terms: a Case in Point

Ethan Bronner

Oct. 13, 2012

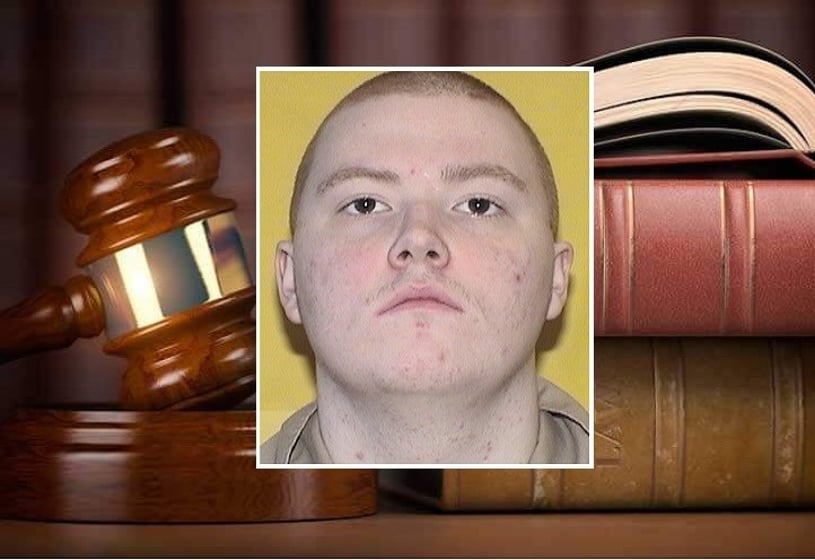

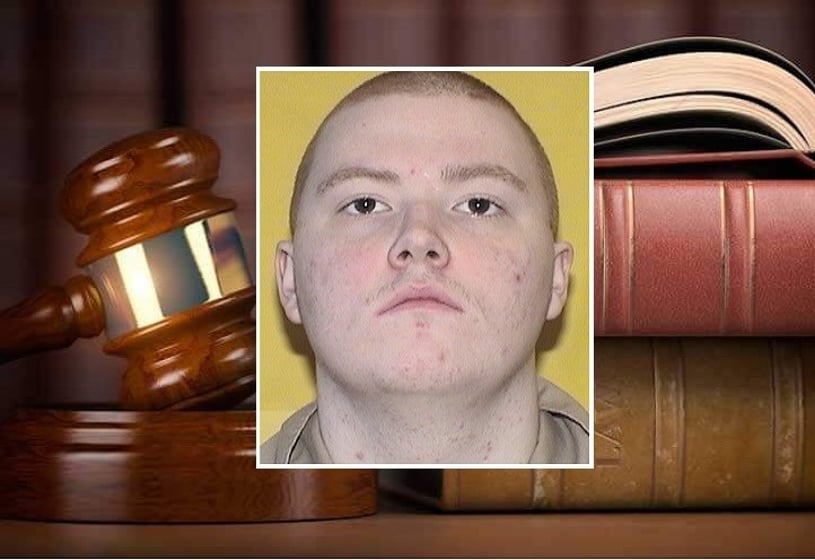

LA BELLE, Pa. — To this day, Maurice Bailey goes to sleep trying to understand what happened on Nov. 6, 1993, when as a 15-year-old high school student he killed his 15-year-old girlfriend, Kristina Grill, a classmate who was pregnant with his child.

“I go over it pretty much every night,” said Mr. Bailey, now 34, sitting in his brown jumpsuit here at the Fayette State Correctional Institution in western Pennsylvania, where he is serving a sentence of life without parole for first-degree murder. “I don’t want to make excuses. It’s a horrible act I committed. But as you get older, your conscience and insight develop. I’m not the same person.”

Every night, Bobbi Jamriska tries to avoid going over that same event. Ms. Jamriska, Kristina’s sister, was a 22-year-old out for a drink with friends when she got the news. Ten months later, their inconsolable mother died of complications from pneumonia. Weeks later, their grandmother died.

“During that year, I buried four generations of my family,” Ms. Jamriska said at the dining room table of her Pittsburgh house, taking note of her sister’s unborn child. “This wrecked my whole life. It completely changed the person I was.”

When the Supreme Court in June banned mandatory life sentences without parole for those under age 18 convicted of murder, it offered rare hope to more than 2,000 juvenile offenders like Mr. Bailey. But it threw Ms. Jamriska and thousands like her into anguished turmoil at the prospect that the killers of their loved ones might walk the streets again.

The ruling did not specify whether it applied retroactively to those in prison or to future juvenile felons. As state legislatures and courts struggle for answers, the clash of the two perspectives represented by Mr. Bailey and Ms. Jamriska is shaping the debate.

…

Mr. Bailey was a good student with no criminal record. He is black and Ms. Grill was white, and many classmates thought of them as a chic couple.

“Reese was someone everyone wanted to be friends with, and so was Krissy,” said Shavera Maxwell, a former classmate, using the couple’s nicknames. “They were deeply in love, and she wanted to keep the baby. He didn’t.”

Kristina’s father, who did not live at home, was known for a bigoted attitude, so Kristina kept her relationship with Maurice secret from him.

Maurice’s father, an electrical engineer who had tensions with white co-workers, also disapproved of the interracial romance. One day when he came home early, he caught the couple in bed. He threw her out and beat Maurice, knocking his head into a wall.

Maurice’s mother, Debra Bailey, felt differently. She welcomed Kristina into her home. “Krissy’s 15th birthday was celebrated with a barbecue in our backyard,” said Ms. Bailey, a database coordinator at Carnegie Mellon University, who is now divorced from Maurice’s father. “Her family didn’t come. Those two were too young to be doing what they were doing, but I told her that if she got pregnant, we would deal with it.”

Kristina told a friend, Pamela Cheeks, the night before she was killed that she was about to tell her family about her pregnancy and that she was meeting Maurice the next day to discuss their future, Ms. Cheeks said in an interview. In her diary, Kristina wrote that Maurice “better show up” at their agreed time and place.

Maurice did meet Kristina that Saturday afternoon at an elementary school playground. He came with a knife, stabbed her repeatedly in the neck and upper body and left her on the ground. Before leaving, he told the police at the time, he zipped up her jacket in a vain effort to stem the bleeding.

He hid the knife in the woods and went home. In the prison interview, he said he remembered very little of the event except that right after stabbing Kristina, her mother, whom he had never met, suddenly came into his mind. When he returned home, the first person he saw was his father. He said he felt an odd sense of relief that the source of tension between them was gone.

Neighborhood youngsters came upon Kristina’s body. Police officers went to her home, where they found her diary with detailed entries of her relationship with Maurice. When the police went to the Bailey home in the middle of that night and woke up Maurice, his mother recalls that he said to them, “I figured you’d come.”

Maurice’s legal defense was built around the pressures he had faced. His father testified in court that he had told Maurice that if Kristina got pregnant, he would kill him. Maurice’s grades were declining as he spent more time with Kristina; he was trying unsuccessfully to break up with her, losing control, growing afraid.

His petition for a new hearing will argue that the pressures he felt as a 15-year-old — a violent father, a pregnant girlfriend — are unique to youth and therefore covered by the Supreme Court ruling. An adult, his lawyers will argue, would have reacted differently.

But Kristina’s sister, Ms. Jamriska, said there was no escaping the brutality of the crime and its premeditation. As she put it: “There are many ways of dealing with pressure. You can run away. I don’t care if you’re 5 or 50, you know that killing is wrong. If you murder your girlfriend and unborn baby, I don’t know if you can come back from that.”

She added that she felt that much discussion of juvenile crime shied away from the horrors of the acts. “They often show pictures of the killers looking like kids who could be trick-or-treating,” she said.