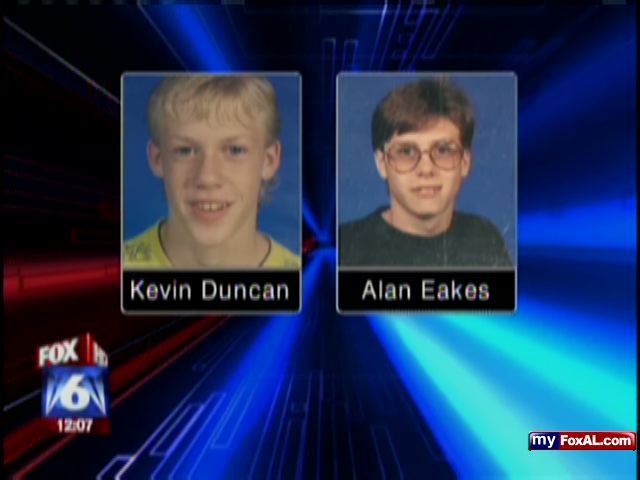

Victims: Kevin Eugene Duncan, 14, and Mollan Allen Eakes, 15

Murderers: Nathan Gast, 15, Carvin Stargell, 17, and Christopher Thrasher, 16

Crime date: February 8, 1992

Weapon: Baseball bat

Murder method: Beating

Sentence: Stargell and Thrasher–life without parole (LWOP); Gast–life with parole

Incarceration status: Gast-released; Stargell & Thrasher-incarcerated at the Limestone Correctional Center

Summary

The killers, who were members of a street gang, beat Kevin and Allen to death. Stargell later beat and attempted to rape a witness to the crime, leaving her to die in a deserted rural area. Stargell and Thrasher were convicted and sentenced to LWOP, while Gast pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life with parole. Gast was later released without the victims’ families’ knowledge.

Details

The assailants, all members of the Insane Gangster Disciples street gang, beat Kevin and Allen to death with a baseball bat and left them in a creek along Alabama 150. Stargell later attempted to rape the only surviving witness, a 14-year-old girl, and severely beat her. He left her to die in a vacant lot in a deserted rural area. She was found after Gast told police where to look for her. The victim was able to testify at trial.

Stargell and Thrasher were convicted and sentenced to life without parole (LWOP). Gast pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. He was later re-sentenced and released without the victims’ families’ knowledge.

After Miller v. Alabama, Thrasher and Stargell were re-sentenced to LWOP. The judge wrote about Thrasher that “The crimes committed by this Defendant are not representative of an immature and impetuous youth, but rather a mature, cold, and calculated criminal eager to cover his tracks at all costs. This Defendant expressed no remorse for his actions at the time of the incident, at his trial, or in the intervening years.” Thrasher’s sentence was affirmed in 2019 by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals.

Murder victim’s relative fight to keep convicted killer behind bars

HOOVER, AL (WBRC) – Relatives of a murder victim from Oneonta continue their fight this week. They are fighting to keep one of their loved one’s killers behind bars.

It has been nearly 19 years since 15-year-old Allen Eakes and 14-year old Kevin Duncan were assaulted with a baseball bat and left to drown near the Shades Creek Bridge off Highway 150 in Hoover.

Three men were convicted in the killings and one of them, Nathan Gast, has a parole hearing this week. Allen Eakes’s brother and sister will be at the hearing to fight the parole petition.

With the holidays approaching, the possibility of gast going free is even more troubling. “Because we miss him, and we know he would be here, and his children would be here, that’s hard,” said Eddie Eakes, the victim’s brother. “All we have to do is go visit his tombstone and grave. That’s all we have to remember him by.”

The offenders are serving life sentences.

Convicted killer Gast released from prison

By The Blount Countian Staff | on July 09, 2014

by Ron Gholson

Nathan Gast, 36, formerly of Hueytown, was released from prison last week, following a Bessemer judge’s ruling vacating his life sentence, and re-sentencing him to time served – about 20 years. Gast was convicted in the 1992 beating deaths of two Blount County boys, Mollan Allen Eakes, 15, and Kevin Eugene Duncan, 14.

The killings were committed by a trio of youths: Gast, Carvin Stargell, and Christopher Thrasher, all teens at the time, and all said to be members of a street gang called Insane Gangster Disciples. Eakes and Duncan were killed with a baseball bat and a girl, Ginger Minor, was beaten and seriously injured, but later recovered to testify against the three. Stargell and Thrasher were convicted and sentenced to life without parole. Gast was given a life sentence.

That fact played a part in his release, according to a statement by Blount County District Attorney Pamela Casey.

“To be clear, Gast did not receive a sentence of life without the possibility of parole when he was sentenced in 1994. Instead, Gast received a sentence of life with the possibility of parole. Gast has been up for parole more than once and has been denied by the Board of Pardons and Parole each time. In essence a judge, who did not hear the facts of the trial, granted a petition to allow Gast to be re-sentenced. It saddens me that the families of the victims have to relive this nightmare and a killer now walks on our streets.”

According to information supplied by Casey from the Alabama Crime Victim’s Rights, item (3) of section 15-23-75 states:“The status of any post-conviction court review or appellate proceeding or any decisions arising from those proceedings shall be furnished to the victim by the office of the Attorney General or the office of the district attorney, whichever is appropriate, immediately after the status is known.”

Betty Klinger, of Straight Mountain, was the mother of Kevin Duncan. She said that neither she nor the Eakes family was notified of the last week’s hearing before Bessemer Circuit Court Judge David Carpenter.

“Why, sure. I’d have been there if I’d known,” she said.“They didn’t let us know anything. It’s like it was done undercover. We should’ve been there. I would’ve been there. It was like they sneaked and did it. They didn’t want us there. He (Gast) is as guilty as the other ones. It was him that held Kevin and Allen while the other one – Stargell – hit’em with the bat.

“The thing that hurts me worst was that Kevin was always in church. He was a good boy. He ended up with that gang only through an accident.”

She explained that he had gone to the skating rink that night, and didn’t have a ride home. He ended up riding with a friend he hadn’t seen in quite a while. He called home to tell his mother that Allen Eakes was giving him a ride home. Instead, the two Oneonta boys were taken to Bessemer with the teens who were in the gang.

“I don’t know how they worked it out to release him. I wish I understood.

Families of two Oneonta boys slain in brutal 1992 beating ‘furious’ over release of one killer

Updated Mar 06, 2019; Posted Jul 08, 2014By Kent Faulk | [email protected]

BIRMINGHAM, Alabama – The families of two Oneonta boys beaten and left to die in a Birmingham creek in 1992 are angry that one of the killers, Nathan Gast, was released from prison last week without their knowledge.

“No one contacted us,” said Eddie Eakes. “They snuck behind our back … They just didn’t give us a chance to do anything.”

“I’m furious. My friends are furious,” said Danny Duncan.

Eakes and Duncan are the older brothers of Mollan Allen Eakes, 15, and Kevin Eugene Duncan, 14 who were beaten with a baseball bat and left face down in Shades Creek along Alabama 150 near Bessemer on Feb. 8, 1992. A 14-year-old girl, whose name was not published, survived the attack and testified.

Gast, who was 15 at the time, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison. Two other teens, Christopher Thrasher and Carvin Stargell, were convicted in connection with the murders and received life without the possibility of parole. All three teens charged were alleged members of the Gangster Disciples street gang and, according to trial testimony, Thrasher was the one who ordered Gast and Stargell to kill the boys.

Gast, however, was released from custody Thursday afternoon after Bessemer Cutoff Jefferson County Circuit Judge David Carpenter re-sentenced Gast to 20 years, time served, and ordered his release. The judge made the ruling based on a motion by Gast’s attorney, Tommy Spina, that was unopposed by Bessemer Cutoff District Attorney Arthur Green.

Efforts to reach Green were unsuccessful prior to publication of this story.

Gast, now 37, had previously sought three times to be released by the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles. Each time, the Duncan and Eakes families were there to oppose it. At the last one in 2010, however, both Spina and a detective in the case came to make a plea to the board, Duncan said.

Duncan and Eakes were also angry at prosecutors for not opposing Gast’s release.

“The prosecutors just sat there and went along with it. And that’s what I don’t understand,” Eakes said.

Eakes said they had been told that Gast would not be released until the next hearing. “I know they didn’t do us right,” he said.

“That’s no way for the state of Alabama to do our family after what we went through,” Eakes said. “What good is a parole board if you’re going to have a judge come in and go against it.”

Eakes, choking back tears, said that his brother’s death tore his family apart. “It’s been like it happened yesterday.”

“There is no getting over it,” he said. “I’ll get over it when my heart takes its last beat.”

Duncan said there have been people executed for less than what those teens did to the two boys. “This boy has committed murder and tried to kill another. … Justice has not been served here,” he said.

“Everybody up here is mad,” Duncan said of the Blount County community.

Duncan said his family contacted Blount County District Attorney Pamela Casey about what to do.

Casey stated in an email that she told them to contact the Alabama Attorney General’s office if they were not happy with the way the cases are being handled. “I told them I would assist them in any way I could with contacting the AG. They haven’t contacted me since that initial contact,” Casey stated in the email.

Spina had argued in his motion that it was never the intent under Gast’s plea for him to serve more than 10 years of the life sentence and that the state would not oppose it. At the time, 10 years would have been the first time he could have received parole. However, later changes in the parole system bumped the minimum time to serve before eligibility to 15 years. With the pardons and parole board repeatedly denying Gast parole, Gast essentially had a “defacto” life without the possibility of parole sentence.

Spina said Gast had cooperated with authorities from the night of the incident and was instrumental in helping find the girl who survived. He said Gast didn’t hit Duncan and Eakes with the bat, but he did move one of the boys and placed him face down in the creek. It turned out the boy died from drowning.

Men re-sentenced for 1992 death of two Oneonta teens found in Shades Creek

Updated Mar 06, 2019; Posted Oct 13, 2017By Ivana Hrynkiw | [email protected]

Two men who were sentenced in 1993 to spend their lives in prison for the death of two young Oneonta teens were re-sentenced today to the same fate.

On Friday, Jefferson County Bessemer Cutoff Circuit Judge David Carpenter re-sentenced Christopher Thrasher and Carvin Stargell to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Thrasher, 42, and Stargell, 43, were originally given the same sentence for the 1992 killings of 15-year-old Mollan Allen Eakes and 14-year-old Kevin Eugene Duncan. Both Thrasher and Stargell were also teenagers at the time.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in an Alabama case in 2012 that a law requiring sentences of life without parole for juveniles convicted of capital murder was unconstitutional. In 2016, the court said that rule is to be applied retroactively to people convicted prior to 2012. The decision opened up the possibility of parole for about 80 prisoners in Alabama, including Thrasher and Stargell.

Judges can still re-sentence the offenders to life without parole, but must have other sentencing options.

On Feb. 8, 1992, Allen and Kevin were found dead in Shades Creek under a Highway 150 bridge. They had been beaten in the head with a baseball bat and left to drown.

The judge cited in his order Friday a psychologist who examined Thrasher said while Thrasher was 16 at the time of the crimes, he had the emotional capacity of a 13-year-old. “It is indisputable that 13-year-olds know right from wrong,” Carpenter wrote.

He wrote that evidence at trial showed Thrasher and his co-defendants contemplated the murders prior to the killing, and Thrasher “planned and attempted to kill the only witness.”

“Thrasher cannot argue that, due to his lack of maturity, he made an impetuous decision and fired a single shot from a gun causing a regrettable death. No, in this case, [Thrasher] instructed other gang members to commit the murders, and when they failed to do so after their first attempt he again instructed the other gang members to kill Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan,” the order showed. Thrasher “was much more than a mere aider and abettor,” Carpenter wrote, and could have prevented the crimes.

Stargell, who was 17 at the time of the murders, had an above-average IQ and was placed in a school program for gifted students, Carpenter wrote. Stargell “expressed his intent” to kill Allen and Kevin by trying to get a gun from a friend, and only taking a bat when he was not able to obtain a gun.

Carpenter wrote that after the “brutal” killing of the boys– describing how Stargell attacked one of the victims who tried to flee– Stargell had a “considerable amount of time” to think about his next move. Instead, raped and beat the surviving, 14-year-old female victim and left her to die, the order stated.

The crimes Stargell committed were “gruesome,” and were actions of a “cold and calculated criminal.”

Carpenter wrote that neither man has ever showed any remorse for their crimes.

Thrasher’s re-sentencing hearing started October 2. In his hearing, prosecutors stated that Thrasher was the leader of the Gangster Disciples street gang, and ordered fellow gang members Stargell and Gast to kill Allen and Kevin. They said he should not be given the opportunity to be released from prison.

Thrasher’s attorneys argued that Stargell and Gast were the ones who actually committed the murders and Thrasher was not present when the boys were killed. His attorneys said Thrasher was a “broken teen,” but has completed several programs while in prison and is currently taking college-level courses, and should be eligible for parole.

Thrasher’s sister Kimberly Thrasher Vance testified at his hearing. She said the Thrasher family moved often when she and her brother were young, and changed schools several times. Vance said Thrasher was a talented athlete, who played baseball and enjoyed skateboarding. Vance said she has never seen her younger brother act violently.

Allen and Thrasher were best friends, Vance said, and Allen was often at the Thrasher household. “They were together all the time… they were glued to the hip.” Vance also said Gast was a frequent guest at their home. “He was like a little brother to me. Allen was too. He was a sweet boy.” Vance said Thrasher would “absolutely not” hurt Allen.

The victims’ family members in the courtroom shook their heads in disagreement while Vance talked about Allen and Thrasher’s friendship.

Vance said on the Friday night Allen and Kevin were killed, Thrasher came to her house and asked for money. Thrasher told his sister he and his friends were going to a party, but she did not know who else was in the car.

“He deserves to be home,” she said.

Stargell’s hearing began Tuesday afternoon. According to a re-sentencing memorandum filed by Stargell’s attorneys Billy Jewell and Edward Reynolds, Thrasher ordered the young female victim to have sex with Stargell on the night of the killings, but she refused. The document states Thrasher then gave Stargell a baseball bat, and Stargell beat the girl.

Stargell denied being a member of the Gangster Disciples gang, but acknowledged Thrasher was a member.

The memorandum states Stargell was raised by his mother after his abusive father left the family. Stargell attended church where his grandfather was a minister and sang in the church choir.

A psychologist stated Stargell suffered from bacterial meningitis as a child, which could have created “behavioral difficulties” as Stargell got older, documents show.

The memorandum states Stargell has spent his prison time “trying to better himself and other inmates,” and has not received any infractions in prison for violent offenses.

Gast was released from prison in 2014, when a judge vacated his life sentence and re-sentenced Gast to the time – about 20 years – he had already served. Prosecutors did not oppose the request by Gast’s attorney for his release, according to court documents. Gast pleaded guilty in 1994 to one count of murder for the boys’ deaths and one count of attempted murder in the girl’s beating.

“Nathan was instrumental in saving [the girl’s] life as he and I rode with the police till 2 am to point out where she had been left,” Gast’s attorney Tommy Spina said.

She survived the attack and testified at Stargell and Thrasher’s trials.

Thrasher v. State

04-12-2019

Facts and Procedural History

In October 1993, Thrasher was convicted of murder made capital pursuant to § 13A-5-40(a)(10), Ala. Code 1975, for the intentional killing of Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan when Thrasher was 16 years old. Thrasher summarizes the facts giving rise to his conviction as follows:

“[O]n February 8, 1992, Carvin Stargell and Nathan Gast, beat Eakes and Duncan before leaving them to drown in a creek in … Jefferson County. Mr. Thrasher was allegedly the orchestrator of the murders and purportedly instructed Stargell and Gast to murder Eakes and Duncan.

“The sole witness to the events was Ginger Minor. Minor was nearly beaten to death by Stargell with a baseball bat and left to die in a vacant lot that same evening. Minor recovered and testified against Mr. Thrasher at trial. Minor testified that Mr. Thrasher was the leader of the gang[] that included Stargell and Gast. Mr. Thrasher, Minor, Stargell, Gast, Eakes, and Duncan were together on February 8, 1992. That night after buying alcohol, the group went to Crown Point Apartments to swim in a hot tub. Mr. Thrasher, Minor, Stargell, and Gast got in the hot tub while Duncan and Eakes remained in the car. Minor testified that Mr. Thrasher made her perform oral sex on Gast and Stargell so that she could become a female member of the group called a ‘disciple queen.’

“Afterwards, Stargell and Gast left Mr. Thrasher and Minor alone in the hot tub. At some point, Duncan came up to the fence around the pool area covered with drool and said ‘Chris, are you crazy? They tried to choke us and said we had to die.’ Minor testified that Mr. Thrasher went up to the

fence to talk to Duncan and was laughing and grinning. Duncan walked back to the car and left with Gast, Stargell, and Eakes. Mr. Thrasher told Minor that Stargell and Gast were taking Eakes and Duncan home. While they were gone, Mr. Thrasher got sick and vomited over the side of the hot tub.

“Stargell and Gast were gone for two hours. When they returned, Eakes and Duncan were not with them. Stargell told Gast to help Mr. Thrasher get dressed while Stargell took Minor’s clothes and dragged her to the car. As he dragged her to the car, Stargell repeatedly told Minor, ‘girl you gotta die.’ Stargell put Minor in the backseat of the car with Gast while Stargell drove; Mr. Thrasher sat in the front passenger seat.

“As they drove around, Gast told Minor that he and Stargell had put the other boys in the creek while Stargell bragged about how they had beat them and that they were dead. They drove to Red Mountain where Stargell said they were going to throw Minor off the mountain, but they did not. Eventually, they ended up in a wooded area in Bessemer, where Stargell tried to rape Minor in the car.

“After the attempted rape, Stargell told Minor to get out of the car for the last part of the initiation. Mr. Thrasher had a baseball bat. Stargell and Mr. Thrasher kept saying that Minor had to die and Stargell was telling Mr. Thrasher to hit her with the bat. At some point, Mr. Thrasher told Minor to say the disciple’s prayer for the gang. Mr. Thrasher picked up a rock but didn’t hit her with it.

“Minor testified that Stargell kept telling Mr. Thrasher to hit Minor, but Mr. Thrasher said he couldn’t bring himself to hit her. At that point, Stargell bashed Minor in the head with the bat. The last thing Minor remembered was a ‘ping’ sound when Stargell struck her head with the bat.”

Thrasher’s brief, at 1-4 (citations to trial transcript and footnote omitted).

At the time of Thrasher’s conviction, § 13A-6-2(c), Ala. Code 1975, authorized only two possible sentences for a capital-murder conviction — death or life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. After Thrasher waived his right to the participation of the jury in the sentencing hearing, see § 13A-5-44(c), Ala. Code 1975, the trial court sentenced Thrasher to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. This Court affirmed Thrasher’s conviction and sentence on direct appeal. See Thrasher v. State, 668 So. 2d 949 (Ala. Crim. App. 1995) (table), cert denied Ex parte Thrasher, 667 So. 2d 750 (Ala. 1995) (table).

On June 4, 2013, Thrasher filed a Rule 32, Ala. R. Crim. P., petition for postconviction relief in which he argued that his sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional under Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012), which prohibits a sentencing scheme that “mandates life in prison without possibility of parole for juvenile offenders.” Id. at 479, 2469. Although the State initially moved to dismiss Thrasher’s petition, the State and Thrasher subsequently filed a joint motion to stay the Rule 32 proceedings pending the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Montgomery v. Louisiana, 577 U.S. ___, 136 S. Ct. 718 (2016), in which the Court granted certiorari to address whether Miller applies retroactively to cases on collateral review. On January 25, 2016, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Montgomery, holding that Miller “announced a substantive rule that is retroactive in cases on collateral review.” Montgomery, 577 U.S. at ___, 136 S. Ct. at 732. Thereafter, the State and Thrasher filed a joint motion in which the State conceded that, in light of Montgomery, Thrasher was entitled to a sentencing hearing in accord with Miller. Thus, on March 9, 2016, the trial court entered an order granting Thrasher’s Rule 32 petition and scheduling a resentencing hearing.

On September 27, 2017, less than one week before the resentencing hearing, Thrasher filed a motion to continue the hearing. In support of that motion, Thrasher argued that the State, allegedly in violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), had suppressed evidence indicating that Eakes’s family and Duncan’s family had made cash payments to Minor prior to her testimony at trial. Specifically, Thrasher argued that, in preparation for the resentencing hearing, the State had provided him with discovery that included a memorandum drafted by prosecutor Ted Mills in February 1994 (“the memorandum”). (C. 212.) According to Thrasher, the memorandum noted that Eakes’s family and Duncan’s family had made the payments to Minor prior to her testimony at trial and that the State “became aware of the payments in February 1994, approximately three (3) to four (4) months after the trial of the defendant.” The memorandum itself, which Thrasher included with his motion to continue, specifically indicates that, “[o]n February 2, 1994, [Mills] received a phone call from Annie Minor, Ginger Minor’s stepmother,” who informed Mills “that she had heard that [Minor] had received some money from the Eakes and Duncan family [sic] sometime after the Carvin Stargell trial.” (C. 217.) According to the memorandum, Mills arranged to meet with Minor at the same time that Andy Bellanca, a captain with the Bessemer Police Department, was to meet with Eakes’s family and Duncan’s family at a different location to “inquire as to whether this information was in fact true and, if so, what was the intent of giving this money.” (C. 218.) Mills reported that Minor told him that

“the money she received was attached to a birthday card and was nothing more than a gift for her sixteenth birthday. She said that she got a hundred dollar bill in a birthday card from the Eakes’ family and another card from the Duncans with a twenty dollar bill inside. [Minor] went on to say that she did not receive any other money from either family except that she did get a Christmas card from the Duncans in December and enclosed inside the card was a twenty dollar bill.”

(C. 218.) After meeting with Minor, Mills discussed his findings with Bellanca, who reported that “what [Eakes’s family and Duncan’s family] told him was almost identical to what [Minor] advised [Mills].” (C. 219.) Mills concluded the memorandum by noting that

“we informed Judge Dan Reynolds of the situation and how we had handled it. Judge Reynolds advised that in his opinion there was nothing to it and that we had handled it properly, and that we should draft a memorandum explaining the entire situation and make it a part of our file for future reference.”

(C. 219.) Given his discovery of the memorandum, Thrasher argued that he required a continuance of the resentencing hearing “so that the facts of the [memorandum] may be investigated further and, if necessary, a new trial sought.” (C. 213.)

On October 2, 2017, the day of Thrasher’s resentencing hearing, the trial court heard the arguments of counsel regarding Thrasher’s motion to continue, and Thrasher’s counsel reiterated that the facts reflected in the memorandum supported a Brady claim. (R. 6, 9.) The trial court noted, however, that the facts in the memorandum

“may be a material issue challenging the conviction in this case — it may be good grounds for appeal and for a Rule 32 action to challenge the conviction but I am not here to review the conviction. I am here to review the sentence and only the sentence. So, that would not be a basis for a continuance.”

(R. 10.) Thus, the trial court denied Thrasher’s motion to continue and proceeded with the resentencing hearing.

During the resentencing hearing, the State did not present any witnesses in its case-in-chief, but relied instead on “the complete transcript, all exhibits and all evidence” from Thrasher’s trial, which the trial court reviewed (R. 35); the presentencing report from Thrasher’s original sentencing hearing, as well as an updated presentencing report filed a few days before the resentencing hearing; and Thrasher’s disciplinary report from the Alabama Department of Corrections. After the State rested, Thrasher presented, among other witnesses, Minor and Dr. Paul James O’Leary, a board-certified psychiatrist. In rebuttal, the State presented victim-impact testimony from Eakes’s brother and Duncan’s brother, and, at the close of the hearing, Thrasher made a brief statement to the trial court.

On October 13, 2017, the trial court entered a detailed judgment in which it resentenced Thrasher to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. (R. 244.) Because Thrasher’s arguments on appeal include challenges to the trial court’s consideration of the evidence presented at the resentencing hearing, we quote the trial court’s judgment at length:

“The United States Supreme Court, in Miller …, held that a judge ‘must have the opportunity to consider mitigating circumstances before imposing the harshest possible penalty for juveniles.’ In Montgomery …, the Supreme Court made the Miller decision retroactive, and in so doing held that prisoners ‘must be given the opportunity to show their crime did not reflect irreparable corruption.’ In making this determination the Alabama Supreme Court held in [Ex parte] Henderson, 144 So. 3d l262, 1263 [(Ala. 2013),] that a sentencing Court must consider fourteen factors, each of which is addressed by this Court below:

“The juvenile’s chronological age at the time of the offense and the hallmark features of youth, such as immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences

“Defendant Christopher Thrasher’s date of birth is July 3, 1975. The Defendant was convicted of a capital murder that took place on February 9, 1992. Therefore, the Defendant was 16 years and 7 months old at the time of the offense. Under current

Alabama law the Defendant would have automatically been treated as an adult for a felony offense. Ala. Code [1975] Section [12-15-204].

“Dr. Paul O’Leary, a board-certified psychologist retained by the defense as an expert witness who examined the Defendant and subjected him to psychological testing, testified that the Defendant had an emotional capacity of a 13-year-old at the time of the offense. Considering that the Defendant was 16 at the time of the offense, the emotional age attributed to him by Dr. O’Leary is not substantially lower than his chronological age. Further, it is undisputable that thirteen-year olds know right from wrong.

“Although Dr. O ‘Leary opined that the Defendant failed to appreciate the consequences of his actions, there is no substantial basis for that opinion. Dr. O’Leary spent very little time with the Defendant and he administered no psychological tests.[]

“Accordingly, this Court finds that the Defendant was not so young in chronological age, nor did he suffer from such a defect of maturity, to not appreciate the nature and consequences of his actions at the time of the offense.

“The juvenile’s diminished culpability

“Dr. O’Leary testified that the Defendant had been intoxicated at the times of the crimes and was sleep deprived. Defendant informed Dr. Alan Blotcky, clinical psychologist for the State, that he had a history of alcohol abuse and marijuana use.

“The evidence presented at trial established that the Defendant and his codefendants contemplated their action and communicated their intentions to one another before the commission of the crimes. Following the murder of the two minor victims, the Defendant planned and attempted to kill the only witness to the crime.

“Defendant described himself as the leader of the gang that killed the victims in this case. He ordered the other gang members to commit the murders. He ordered the only witness to the crimes to perform sexual acts with his codefendants, the other gang members, to say a gang prayer, and then he attempted to kill the witness.

“The Court finds that the Defendant formulated and carried out a plan to kill and attempted to reduce the chances of being caught by trying to kill the witness to the crime.

“The circumstances of the offense

“The minor victims in this case, Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan, were 16 and 15 years old at the time they were brutally murdered by being beaten and left in a creek to drown. This Defendant was the self-proclaimed leader of the gang that committed these brutal murders and he instructed the other gang members to commit the murders. This Defendant also savagely beat the only surviving witness, Ginger Minor, and left her for dead in a deserted rural area and covered her body in an effort to conceal her.

“With regard to the two victims murdered, the Defendant cannot argue that, due to his lack of maturity, he made an impetuous decision and fired a single shot from a gun causing a regrettable death. No, in this case, the Defendant instructed other gang members to commit the murders, and when they failed to do so after their first attempt he again

instructed the other gang members to kill Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan. According to the coroner, each of the victims suffered at least five blows to the head with a blunt instrument. They were then dumped into a creek where they drowned.

“After Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan were brutally murdered on the instructions of this Defendant, this Defendant beat Ginger Minor with a baseball bat. Ginger Minor suffered skull fractures, a bruise on the brain, fractures to her hands and feet and a broken nose. Ms. Minor was left in a vacant lot to die. She was found only because a codefendant, Nathan Gast, told police where to look for her. Upon first regaining consciousness Ginger Minor was asked, ‘who did this to you?’ She responded, ‘Chris’ Thrasher.

“The extent of the juvenile’s participation in the crime

“The circumstances surrounding the murders of Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan, as well as the beating of Ginger Minor, were gruesome. These gruesome crimes were planned, ordered, and committed by this Defendant.

“This Defendant instructed his codefendant to kill the victims. When the first attempt to do so failed, this defendant again instructed his codefendants to kill. After his codefendants told him they had carried out his order, and after Defendant saw blood evidence of the crime in the car, this Defendant brutally beat the only witness who represented a threat to being prosecuted.

“The evidence presented at trial unequivocally demonstrated that this Defendant, Christopher Thrasher, was much more than a mere aider and abettor in the deaths of Allen Eakes and Kevin Duncan, as well as the attempted murder of Ginger Minor. Defendant Christopher Thrasher gave the

order to kill. As the self-proclaimed leader of the gang, this Defendant also had the apparent authority to prevent these brutal crimes.

“The facts of the case show that the Defendant’s actions were those of a cold and calculated criminal.

“The juvenile’s family, home, and neighborhood environment

“The evidence at trial and at the resentencing hearing is that the Defendant had a good relationship with his mother, who was loving and attentive. He had very little relationship with his father, who was an alcoholic. Dr. Alan Blotcky’s report from 1992 states that the Defendant quit school in the ninth grade and had charges of truancy, intoxication, assault with a weapon, and violation of probation.

“Dr. O’Leary testified that the Defendant has done well in a structured environment. In support of this opinion he notes that Defendant’s behavior became worse after he dropped out of school. However, the Defendant’s history does not support this conclusion.

“The Pre-sentencing Report dated September 3, 1993, states that the Defendant had legal problems while in school, he admitted to cutting classes, and he dropped out of school. Because of the trouble Defendant was getting into he was sent to a more structured environment, Big Oak Boys Ranch, where he subsequently ran away. At that time, he was on juvenile probation and was described by his probation officer as ‘a terrible probationer.’

“Further, Defendant’s record of thirty-two disciplinary infractions while in the custody of the Department of Corrections indicates that even in a

highly structured environment Defendant has failed to conform to the restrictions placed on him.

“The juvenile’s emotional maturity and development

“Although Dr. Paul O’Leary testified that the Defendant possessed an emotional age of a thirteen-year-old, he also admitted that Defendant’s leadership position in a gang demonstrated a level of control, maturity, and obvious leadership. There is no other substantial evidence that this Defendant suffered from delayed emotional development. This Court finds that the Defendant demonstrated sufficient emotional maturity and development.

“Whether familial and/or peer pressure affected the juvenile

“The Defendant has proclaimed himself to be the leader of the gang that killed the minor victims. The testimony from trial establishes that his codefendants looked to him as a leader, and took instructions from him. The Defendant ordered the other defendants to kill the minor victims. At a minimum, Defendant had the authority to prevent the crimes committed by the codefendants. The Court finds that there was no familial or peer pressure that affected his behavior when the crimes were committed.

“The juvenile’s past exposure to violence

“There was no evidence presented that the Defendant had been impacted by any past exposure to violence against him whatsoever. Defendant does, however, have prior charges of assault with a weapon. Further, Defendant admits to being a leader in a street gang.

“The juvenile’s drug and alcohol history

“The Defendant has admitted drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana on the night of the crimes. Dr. O’Leary testified that because of the Defendant’s age the use of alcohol resulted in his diminished culpability. Defendant’s records from the Department of Corrections indicate[] that he still has issues with substance abuse.

“The juvenile’s ability to deal with the police. The juvenile’s capacity to assist his attorneys

“These two prongs were addressed together in Miller wherein Justice Kagan wrote that a failure to consider these prongs ‘ignores that he might have been charged and convicted of a lesser offense if not for incompetencies associated with youth — for example, his inability to deal with police officers and prosecutors (including on a plea agreement) or his incapacity to assist his own attorneys.’

“As reported by Dr. Blotcky, the Defendant understood how the criminal justice system worked, and he had no mental defects that would prohibit him from assisting his attorneys. Thus, there is no reason to believe that the Defendant was unable to deal with police officers and to assist his attorney. In fact, the Defendant had minor criminal charges in his past, so he therefore had dealt with police before.

“No evidence was presented at the resentencing hearing that indicates that the Defendant had any trouble dealing with police or assisting his attorneys.

“The juvenile’s mental health history

“Although the record reflects that the Defendant had been treated with depression at age 14, and was in the low average range of IQ testing, he appeared to Dr. Blotcky as ‘fairly bright, thinking was

logical, rational, and coherent.’ Defendant has no other history of mental health conditions.

“The juvenile’s potential for rehabilitation

“While incarcerated in the Alabama Department of Corrections the Defendant has been found guilty of approximately 38 disciplinary infractions. Some of his infractions are major, violent infractions. In June of 2013 the Defendant filed the Rule 32 Petition that led to this resentencing hearing. At that time, the Defendant should have known that he had a chance at parole at some point. And yet, Defendant has been found guilty of at least seven disciplinary infractions since then. Moreover, one witness for the defense testified that she has been in communication with this Defendant in ‘recent months’ by cell phone from prison, indicating that this Defendant is still in violation of institutional rules.

“At his resentencing hearing the Defendant was given an opportunity to make a statement. Defendant’s statement was very brief. He expressed no specific remorse, nor did he specifically take responsibility for actions. Instead, the Defendant deflected responsibility for the crimes on one of his codefendants. In an article written by the Defendant, and admitted at the resentencing hearing, the Defendant also denied responsibility for his crimes.

“In Dr. Blotcky’s report following his evaluation of March 10, 1992, the defendant ‘showed absolutely no emotion when discussing the crimes,’ and displayed ‘no evidence or remorse or guilt.’ Dr. Blotcky reported that the Defendant ‘seemed cocky, glib, and bored,’ and that he ‘comes across as sullen, guarded, angry, and totally unremorseful,’ and he has ‘a tendency to blame others.’ Dr. Blotcky concluded that the Defendant

‘is at high risk to be involved in criminal acts in the future,’ and that ‘he can be quite dangerous.’

“Any other relevant factor related to the juvenile’s youth

“This Court finds that there is no other compelling evidence related to the Defendant’s age, over 16 years, at the time of the crime that should result in a change of his sentence. The jury convicted the Defendant of Capital Murder, for the killing of two minors, after being presented with all the evidence in this case. Judge James Hard IV then appropriately sentenced the Defendant to Life Without Parole for his cold, calculating, cruel, and heinous crime against innocent minor victims. Judge Hard’s sentence would have been appropriate even if he had the option to sentence the Defendant to a lesser term.

“Conclusion

“Defendant Christopher Thrasher participated in planning, and ordered the brutal murder of two minor victims. After the two minors were brutally beaten to death, and after this Defendant was informed that they had been killed, and after he was presented with the blood evidence of the murders on the murder weapon, he attempted to cover up evidence of the crimes by trying to kill the only witness who could lead to a prosecution. The crimes committed by this Defendant are not representative of an immature and impetuous youth, but rather a mature, cold, and calculated criminal eager to cover his tracks at all costs. This Defendant expressed no remorse for his actions at the time of the incident, at his trial, or in the intervening years.

“Notably, Defendant’s conduct since his incarceration demonstrates that his crime was not the result of ‘transient immaturity or youth,’ but instead was the product of ‘irreparable corruption.’

Click v. State, 215 So. 3d 1189, Ala. Crim App. (2016). Considering all the circumstances, this Court finds that this is the rare case where the original sentence of the trial judge was an appropriate sentence for a juvenile defendant convicted of capital murder.”

(C. 244-49.) (Internal citations omitted.)

On November 13, 2017, Thrasher filed a “motion for new trial and request for an evidentiary hearing on the same” in which he argued that he was entitled to a new trial based on the facts supporting his Brady claim and sought an evidentiary hearing on that claim. (C. 250.) Thrasher also argued that his sentence is “contrary to the weight of the evidence” and that, in resentencing him, the trial court “failed to acknowledge” the factors set forth in Ex parte Henderson, 144 So. 3d 1262 (Ala. 2013). (C. 258.) Thrasher’s motion was denied by operation of law on December 12, 2017, and Thrasher filed a timely notice of appeal on January 12, 2018.