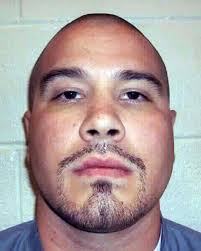

Victims: Arjin Pechpho, 24, and her son Jonathan Smith, four

Age at time of murder: 16

Crime location: Las Vegas

Crime date: October 22, 1993

Crimes: Robbery, home invasion, kidnapping, double murder, & murder of a child

Weapon: A cord; a bathtub, water, & a hairdryer for electrocution; and a kitchen knife

Murder method: Strangling & stabbing (plus attempted electrocution)

Murder motivation: Robbery

Convictions: One count of burglary, one count of robbery with the use of a deadly weapon, one count of first degree murder, and one count of first degree murder with the use of a deadly weapon

Sentence: Death later reduced to life without parole (LWOP)

Incarceration status: Southern Desert Correctional Center

Summary

Domingues brutally robbed and murdered Arjin and her four-year-old Jonathan in 1993. The killer broke into the victims’ home and waited for them to enter. When they did so, he ambushed them. The home-invader first tied up Arjin and strangled her. Next, he dragged the dead mother’s body to the bathtub, filled it with water, and ordered little Jonathan to get into the tub. Domingues attempted to electrocute the four-year-old by throwing a hair dryer in the tub. When that didn’t work, he stabbed the child to death.

Domingues was found guilty and sentenced to death. In 2010, his sentence was reduced to LWOP.

Details

Domingues v. State

On the evening of October 22, 1993, Arjin Chanel Pechpo and her four-year old son, Jonathan Smith, were murdered in their home in Las Vegas, Nevada. Appellant Michael Domingues waited for Pechpo behind her front door; when she entered with Jonathan, Domingues threatened her with a gun, tied up her hands, and strangled her with a cord. Domingues then dragged Pechpo’s body to the bathtub, filled it with water, ordered Jonathan to get into the tub, and threw a hair dryer into the tub in an attempt to electrocute the boy. When the electrocution attempt failed, Domingues stabbed Jonathan with a knife numerous times, killing him.

The police investigation did not link Domingues to the crimes until November 19, 1993, when police learned that Domingues had used Pechpo’s credit card by forging her name to purchase several items at a local Target department store. In relation to the Target incident, Domingues’s accomplice and friend, Joshua Rodgers, explained that Domingues commented that he had strangled a woman because she was yelling at his then-girlfriend, Michelle Fleck (“Michelle”). At a subsequent interview in November 1993, Domingues admitted to police only that he entered the house, stole the credit card and used it at the Target store.

On January 3, 1994, the police received a call from Paul Fleck, Michelle Fleck’s father, and the next-door neighbor to the Pechpo residence. When police later met with Fleck, he turned over a television set and a VCR, as well as other items reported to have belonged to Arjin Pechpo. On January 4, 1994, the police returned to the Fleck residence and spoke with Michelle. During this interview, Michelle fully implicated Domingues in the murders. Her statement included crime details which had not been previously released to the media or to any private citizens, including the victims’ family.

Michelle related that approximately two weeks prior to the murders, Domingues told her that he wanted to steal a car from a particular person living in the neighborhood and that he wanted to beat them up and kill them if they put up a fight. Three days before the murders, Michelle saw Domingues braiding some cord similar to that used by her father in his plumbing business. Thereafter, on the night of October 22, 1993, Michelle recalled that Domingues had come to her window dressed entirely in blacka black-hooded shirt over a long-sleeved black shirt and black sweat pants. After Michelle climbed out of the window, Domingues pointed to a burgundy car and asked her, “How do you like my new car?” When Michelle asked Domingues where he had gotten the car, he replied that he had killed the woman next door, pointing to the Pechpo home. At this point, Michelle did not know whether or not to believe Domingues’s declaration.

Domingues explained that they were going to California, and Michelle got into the car, which she later identified as belonging to Pechpo. Michelle noticed a plastic bag containing a knife, some yellow rope and an open wallet on the floor of the vehicle. She recognized the knife as one from her kitchen. Michelle also saw a gun and recognized it as belonging to her father. After some time, Michelle informed Domingues that she needed to use the restroom. Domingues exited the freeway, and Michelle explained that she wanted to go home. Domingues began yelling, “I did it for you.” On the way back to Las Vegas, Domingues kept saying to Michelle that he had strangled “her.” At a trailer park, Domingues stopped the car and discarded some of the black clothes he was wearing, a plastic grocery sack, some cord, the wallet and a child’s car seat into a trash dumpster. Domingues explained that he was getting “rid of evidence.” Domingues did not throw away the knife. When the couple *1370 returned to Michelle’s house, Domingues directed her to wash the knife with bleach. Michelle washed the knife noticing that it had blood on it.

Summarizing various discussions she had with Domingues that night, Michelle recounted Domingues’s admissions about the crimes. Domingues gained access to Arjin Pechpo’s house by breaking the kitchen window. He waited behind the door for Pechpo to come home. Domingues stated that he was waiting for her so that he could kill her and steal her car. When Pechpo and her son entered the house, Domingues placed a gun to Pechpo’s head and ordered her to lie down. Thereafter, he tied her hands with the cord Fleck later saw in the car and strangled her with the cord. Domingues then dragged Pechpo’s body to the bathroom and put her in the tub. Domingues then instructed the little boy, Jonathan, to take off his pants and get into the tub. He handed the boy a hair dryer in an effort to electrocute him. When this proved ineffective, Domingues stabbed the boy repeatedly with Fleck’s kitchen knife.

Domingues stayed the night with Michelle. The next morning, October 23, 1993, Michelle noticed a cut on Domingues’s finger. When Fleck asked what had happened, Domingues explained that the injury occurred as he was choking the woman. Michelle related that after the murders, Domingues had brought her a television set and two VCR’s and intended them to be payment to her father for a phone bill. He also brought her jewelry, hair curlers, curling irons, a dress, some belts and a black teddy bear. After her January 4, 1994, interview with the police, most of these items were turned over to the police. Michelle also turned over the knife and the black-hooded T-shirt Domingues had worn.

Michelle acknowledged that she initially gave false information to the police by telling them that she had seen a car with some black men speed away on the night of the murders. She also explained that she was extremely afraid of Domingues in that he “told me if I told anybody he would kill my whole family in front of me. He would tie me up and then torture me until I die.”

After the January 4, 1994, interview, police arrested and charged Domingues with first degree murder for Pechpo’s death, first degree murder with the use of a deadly weapon for Jonathan’s death, robbery with use of a deadly weapon, and burglary. After a trial, the jury found Domingues guilty of all crimes charged. After a penalty hearing, Domingues was sentenced to death for each of the murder counts, two consecutive fifteen-year terms of imprisonment for robbery with use of a deadly weapon, and ten years of imprisonment for the burglary.

On appeal, Domingues first argues that the district court erred in denying his pre-trial petition for writ of habeas corpus, in that insufficient evidence existed to support use of a deadly weapon for the robbery and murder charges in light of the “corpus delicti rule.” Specifically, Domingues argues that there is absolutely no proof, independent of his own admissions to Michelle Fleck, that either a gun or a knife was used in either the killing or robbery of Pechpo. He contends that because the deadly weapon enhancement was appended to the robbery and murder counts, use of a deadly weapon became an element of each offense. Domingues claims that the “corpus delicti rule” precluded consideration of his admissions at the preliminary hearing as sufficient evidence to support a finding of probable cause for each offense.

DOMINGUES v. STATE

Supreme Court of Nevada.

Michael DOMINGUES, Appellant, v. The STATE of Nevada, Respondent.

No. 29896.

Decided: July 31, 1998

FACTS

On October 22, 1993, sixteen-year-old Michael Domingues murdered a woman and her four-year-old son in the victims’ home. In August 1994, a jury found Domingues guilty of one count of burglary, one count of robbery with the use of a deadly weapon, one count of first degree murder, and one count of first degree murder with the use of a deadly weapon. At seventeen years of age, Domingues was sentenced to death for each of the two murder convictions. On May 30, 1996, this court upheld Domingues’ convictions and sentence. Domingues v. State, 112 Nev. 683, 917 P.2d 1364 (1996), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 968, 117 S.Ct. 396, 136 L.Ed.2d 311 (1996).1

On November 7, 1996, Domingues filed a motion for correction of illegal sentence, arguing that “execution of a juvenile offender violates an international treaty ratified by the United States and violates customary international law.” Article 6, paragraph 5 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) provides that: “Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age and shall not be carried out on pregnant women.” ICCPR, Dec. 19, 1966, art. 6, S. Treaty Doc. No. 95-2, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, 175.

In 1992, the United States Senate ratified the ICCPR, with the following pertinent reservation and declaration:

That the United States reserves the right, subject to its Constitutional constraints, to impose capital punishment on any person (other than a pregnant woman) duly convicted under existing or future laws permitting the imposition of capital punishment, including such punishment for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age.

․

That the United States declares that the provisions of Articles 1 through 27 of the [ICCPR] are not self-executing.

138 Cong.Rec. S4781-01, S4783-84 (daily ed. April 2, 1992) (emphasis added).

At a hearing on Domingues’ motion to correct the illegal sentence, the district court concluded that the sentence was not facially illegal and, thus, it lacked jurisdiction to correct the sentence; on March 7, 1997, the district court issued an order denying Domingues’ motion. Domingues appeals from this order.

Man murdered two neighbors

By Peter O’Connell

Review-Journal

The U.S. Supreme Court will not consider the case of a convicted murderer who said his execution would violate the terms of an international treaty.

Michael Domingues was 16 in 1993 when he killed Arjin Pechpho, 24, and her 4-year-old son, Johnathan Smith, at their home in Las Vegas. Domingues, who lived next door, was sentenced to death a year later by a Clark County jury.

He subsequently sought to have that sentence overturned by the Nevada Supreme Court on the grounds it is an illegal sentence under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

That treaty, ratified by the Senate in 1992, stipulates that a death sentence shall not be imposed on people who commit crimes before age 18 or against pregnant women.

In a 3-2 decision, the Nevada Supreme Court in July 1998 pointed out that although the Senate ratified the treaty, it also reserved the right to impose capital punishment on any person, including those under 18.

Domingues then sought to take his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court on Monday rejected his appeal. . .

Domingues, now 22, was 17 years old when he was sentenced to die. He was the youngest person in modern history to receive a death sentence in Nevada.

Prosecutors contended that Domingues went to Pechpho’s residence at 4017 Maple Hill Road to steal her car. They said the teen-ager waited inside the residence for the woman and her son to return with the vehicle, then killed them both to eliminate witnesses.

Court allows three in Nevada to live

• Michael Domingues was 16 when he killed a woman and her 4-year-old son during a robbery in Las Vegas in 1993. Domingues, according to Roger, tried to electrocute the child in the process of killing him.

Domingues was sentenced to death in 1994, making him the youngest person in modern history to receive a death sentence in Nevada. Prosecutors and defense attorneys said Domingues’s sentence is nullified by Tuesday’s ruling.

• Shane Myers. Myers is one of a group of teens charged

5 former teen offenders free in Nevada after law change

LAS VEGAS (AP) — Five inmates convicted of homicide as juveniles have gone free in Nevada since state lawmakers banned life-without-parole for minors and allowed those already serving such sentences to make a case for release, state prison officials say.

The 2015 law provided parole eligibility to inmates who were juveniles at the time of their crimes, had already served 20 years in prison, and were not convicted of multiple murders. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court banned mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles in homicide cases. Last year, after Nevada passed its law, the justices applied the ruling retroactively to those already in prison on such sentences. A month before that Supreme Court decision, the Nevada’s law was upheld by the state’s high court.

“These are not partisan issues. We’re talking about kids,” said state Assemblyman John Hambrick, the Republican author of the Nevada law. He also served on a state Supreme Court commission that studied juvenile justice reform and chaired a state Juvenile Justice Commission.

“Kids process information differently and make decisions differently than adults,” said Hambrick, a former federal law enforcement agent in his fifth term in the Legislature. “Sociologically, the human brain is not mature at 16, 17 — even 18-year-olds.”

The law made 24 juvenile homicide offenders eligible for sentence reviews, state prisons analyst Nancy Flores said. Nineteen are still in prison, including two whose death sentences were converted to life without parole.

Michael Domingues was 16 years old when he strangled his 24-year-old neighbor in Las Vegas and stabbed her 4-year-old son to death in October 1993. He was 17 when he was convicted of double murder and sentenced to be executed. His sentence was converted in 2010 to life without parole.

Domingues and his lawyer, Lisa Rasmussen, want the Nevada Supreme Court to rule him constitutionally entitled to a new sentencing hearing at which he could argue that juvenile offenders are too neurologically and psychologically immature to face a lifetime behind bars. A ruling is pending.

The state Legislature passed more laws this year giving judges discretion to reduce by about one-third the sentences of offenders who are 17 or under when they commit their crimes. The governor signed the measure into law May 31.

Lawmakers also approved, and the governor signed, a law that lets the state parole board commute death sentences for juveniles to sentences allowing the possibility of parole.