Victims: Wayne Stock, 58, and Sharmon Stock, 55

Age at time of murders: 17

Crime location: Murdock

Crime date: April 17, Easter Sunday, 2006

Partner in crime: Gregory Fester, 19

Weapon: 12 gauge shotgun & .410 shotgun

Murder method: Gunshots to the head and face

Convictions: Guilty plea to two counts of second-degree murder

Sentence: Life in prison

Incarceration status: Incarcerated at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women

Summary

Fester and Reid invaded the Stocks’ home during a massive multi-state violent crime spree. Wayne, a respected farmer and business owner, was shot in the head while his wife Sharmon, a former school teacher, was shot in the face. Both killers pleaded guilty and were sentenced to life in prison. Their sentences have been upheld on appeal.

Two additional men, Matthew Livers and Nicholas Sampson, were charged. Charges were dropped and Livers and Sampson, both cousins, later won a civil lawsuit.

Details

They shot two people during a farmhouse robbery. Charges against two other suspects are dropped.

March 20, 2007|From the Associated Press

PLATTSMOUTH, NEB. — The two Wisconsin residents who broke into a farmhouse 11 months ago and shot a couple to death were each sentenced Monday to consecutive life sentences in prison. Authorities said that Gregory Fester, 20, and Jessica Reid, 18, broke into the house in rural Murdock on April 17 intending to commit robbery. They shot and killed Wayne and Sharmon Stock.

Read local media coverage of this brutal crime.

Was Nebraska Couple’s Murder Revenge or Random?

(ABCNEWS.com)By GEOFF MARTZSept. 3, 2010

For legendary crime scene investigator David Kofoed, this was one of the bad ones.

“It was like something out of Truman Capote’s ‘In Cold Blood,’” he said.

Well-liked couple Wayne and Sharmon Stock were found viciously murdered in their Nebraska farmhouse, apparently killed on Easter Sunday, 2006.

The tiny town of Murdock, Neb., where many hadn’t locked their doors for years, was in utter disbelief.

“It was, of course, total shock,” said former pastor Jon Wacker. “There were all kinds of theories running around.”

But to Kofoed, a veteran investigator of the Douglas County Crime Lab, the crime had all the earmarks of a revenge killing by someone the Stocks had to have known.

“We didn’t see any indication of robbery…so we thought this has got to be a personal attack,” he said.

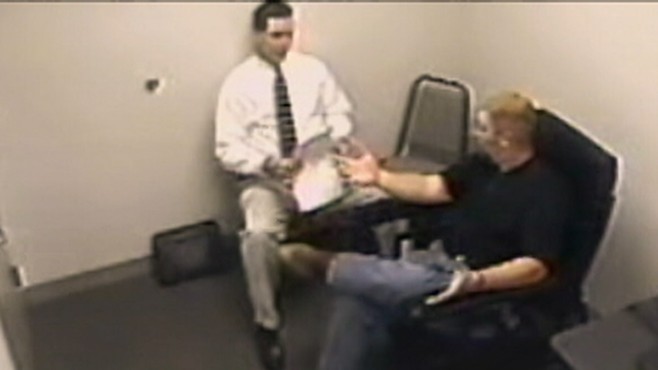

Attention quickly focused on the Stocks’ 28-year-old nephew Matthew Livers, who was reportedly angry at the couple over a money matter. Livers submitted to a polygraph test, which he was told he failed. After initially vehemently denying responsibility, Livers eventually began to break down under videotaped police questioning.

Interrogator: The truth is, you got a gun, right or wrong?

Golden Ring Turns Murder Case Upside Down Watch Video

A Murder, Two Suspects, Two Confessions Watch Video

Investigator Accused of Planting Evidence Watch Video

Livers: Right.

Prompted by police questioners, Liver gradually confessed to the crime and implicated his cousin Nick Sampson — giving many details.

Livers: I put the gun to her face and blew it away… and then as I headed out I just stuck it to him and blew him away.

Livers told police he and Sampson had been driving a tan car that night — and witnesses came forward who had spotted a suspicious tan car speeding on a road near the farmhouse the night of the murder. Even more damning, the car Livers said they had used had been taken to a car wash within hours of the murder.

“The car was detailed at 5:30 in the morning on that same day,” said Kofoed, “which is an awful odd coincidence.”

But there was no corroborating physical evidence — no DNA or blood to link the two men to the crime scene. So, police sent in the CSI lead investigator, Kofoed — famous in Nebraska for being able to find evidence when no one else could.

Kofoed went into the car Livers said he had used to commit the crime and — although earlier processing of the car had turned up nothing — found one single drop of blood from the crime scene. The case was made — and Livers and Sampson were charged with murder.

But there was this one unresolved detail: a golden ring found on the kitchen floor in the murder house. It didn’t belong to Wayne or Sharmon Stock or any of their friends — and it didn’t belong to Livers or Sampson either. It was a minor loose end that would ultimately turn the case upside down.

Golden Ring Turns Case Upside Down

Christine Gabig, a young investigator from the Douglas Crime Lab, set out to trace the gold ring found in the murdered couple’s kitchen, which bore an inscription — “Love always, Cori and Ryan.”

“The inscription is pretty unique because it’s on the outside of the ring,” Gabig said. It also had a jeweler’s mark on it. Gabig was able to trace the ring to a company in New York State that had just gone out of business.

“When I called, it was their last day in the office. This woman was just there cleaning out the office,” she said.

A day later, and the ring might never have been traced. Seventy phone calls later, Gabig had discovered that the ring belonged to a man named Ryan in Wisconsin, but it had been stolen, along with his red pick-up truck, two days before the murder. A young couple was in custody, believed to have stolen that truck as part of a multi-state crime spree: 17-year-old Jessica Reid and her boyfriend 19-year-old Gregory Fester.

New Suspects Emerge: Teen Couple on Crime Spree

Reid was a former honors student who fell in love with Fester, who had a history of hot-wiring cars and burglary.

Under videotaped questioning, the couple admitted to killing the Stocksduring a late-night random robbery on Easter Sunday. The ring — along with two other pieces of evidence found at the scene — had a mixture of DNA from Reid and Fester, as well as blood from the murders. It seemed like an air-tight case.

But police believed Livers and Sampson must have been involved as well. After all, they had a confession, and the blood evidence found in the car by Kofoed.

Reid said interrogators tried to pressure her into saying Livers and Sampson were also involved in the murders. After being threatened with the death penalty, she said she briefly did implicate Livers and Sampson, but then almost immediately recanted.

Courtesy Stock FamilyWayne and Sharmon Stock are pictured in this… View Full Caption

Golden Ring Turns Murder Case Upside Down Watch Video

A Murder, Two Suspects, Two Confessions Watch Video

Investigator Accused of Planting Evidence Watch Video

For police, the sticking points were the confession and the blood evidence. If Livers and Sampson didn’t kill the Stocks, why would Livers have confessed? And how did blood from the crime scene end up in their car?

“Did anyone begin to wonder about your blood specimen?” “20/20’s” Deborah Roberts asked Kofoed.

“Obviously, eventually they did,” said Kofoed.

One of the people who wondered was Special Prosecutor Clarence Mock. And his answer would rock the world of Nebraska law enforcement.

“The evidence demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt that David Kofoed planted the DNA,” said Mock.

Legendary CSI Investigator Accused of Planting Evidence

The seemingly air-tight case against Livers and Sampson was beginning to unravel.

Special Prosecutor Mock said the lie detector test Livers was told he failed had apparently been incorrectly scored. And, he said, Livers, a suggestible man of limited capacity, simply confessed to a crime he did not commit.

Mock said Kofoed, believing Livers and Sampson to be guilty, planted evidence to make sure they would be convicted.

But could the legendary lead CSI investigator really be guilty of planting evidence? Kofoed protested his innocence, and passed two polygraph tests. He was tried in federal court on the narrow charge of misdating a report and found innocent.

However, he was tried a second time in Cass County on broader charges of falsifying evidence — and this time, he was found guilty.

Kofoed continues to deny the charges.

“If I was to plant evidence — and I didn’t — but if I was to plant evidence, I would’ve locked those guys tight. We had all of their clothing. We had their shoes. We had a pair of Nick Sampson’s jeans with a possible blood stain on them,” he said. “It doesn’t make any sense to me at all that we would plant evidence in somebody else’s car.”

Special prosecutor Mock disagrees: “It was a much more believable scenario that a small amount of blood might have been overlooked at a location where some other technician had failed to swab than something very obvious.”

Kofoed’s lawyer, Steve Lefler, argues that Kofoed was the guy who authorized Gabig to track down the ring that would eventually establish Livers’ and Sampson’s innocence.

“Does it make any sense,” said Lefler, “that David on the one hand is going to try to convict these two guys and on the other hand say to Christine, ‘Go find this?’”

Kofoed told “20/20” it all boils down to contamination. He believes the test kit he used to swab the car had also been present at the Stock house where it became contaminated with blood from the crime scene.

HandoutJessica Reid and Matthew Livers both confessed to the murder of Wayne and Sharmon Stock. Watch the two confessions. Can you identify the false confession?

Golden Ring Turns Murder Case Upside Down Watch Video

A Murder, Two Suspects, Two Confessions Watch Video

Investigator Accused of Planting Evidence Watch Video

But Mock said there would have been no need for a kit used to determine if there was blood present at a crime scene as bloody as the Stock murder house. “This was one of the bloodiest scenes that I’ve observed,” Mock said. “It was obvious that there was blood.”

As the reverberations from the case begin, the civil lawsuits for police misconduct, the re-examination of other cases Kofoed was involved in — what everyone involved agrees on is how precarious justice sometimes seems.

“But for the finding of the ring,” said Mock, “Livers and Sampson may very well be on death row right now.”

Kofoed is currently serving a 20-month to 4-year sentence for manufacturing evidence; he is appealing. Jessica Reid and her boyfriend are serving life-sentences for murder. Matthew Livers and Nick Sampson are currently suing police investigators for alleged misconduct and fabrication of evidence.

Consecutive life sentences handed down in Murdock murders

Two Wisconsin residents who pleaded guilty earlier this year to the 2006 slaying of a rural Murdock couple each will serve consecutive life sentences for the crime.

- CARA PESEK / Lincoln Journal Star

- Mar 19, 2007

P

LATTSMOUTH — Tired, irritable and coming down from a cough-suppressant induced high, Gregory Fester II and his girlfriend, Jessica Reid, looked for a house suitable to rob.

It was Easter 2006, late at night or maybe early the next morning. They were in a stolen truck on a road trip which began in Wisconsin and extended into Iowa, Nebraska and eventually Louisiana.

Reid, then 17, would point out a promising house, which Fester would find something wrong with.

They needed a place where no one was at home, where it looked like they could find some money to buy gas and food. After perhaps half an hour, Fester pointed out the rural Murdock farmhouse belonging to Wayne and Sharmon Stock.

“I thought we might have gotten lucky with a huge house with no one home,” Reid wrote in a statement, which District Judge Randall Rehmeier read during Reid and Fester’s sentencing Monday.

Everyone in Murdock and Cass County knows now that Wayne and Sharmon were home, that a son found them shot to death April 17.

Monday, Fester and Reid were each given two consecutive life sentences for killing Wayne, a respected farmer and business owner, and Sharmon, a former teacher who was caring for her elderly mother.

In January, Reid and Fester plead guilty to two counts each of second-degree murder. In addition, Fester plead guilty to one count of use of a firearm to commit a felony, for which he received a 10-20 year sentence on Monday.

The Stocks were active in their church and community, Cass County Attorney Nathan Cox said during Monday’s hearing. They were parents of three, grandparents of four. They were close with their large extended family, too.

“More than once, I heard that they were the mortar that held the family together,” Cox said, “and that has been torn away.”

More than 70 people filled the courtroom, including the Stocks’ children — Steve Stock, Tami Vance and Andrew Stock — who had been absent from the earlier hearings.

Monday brought some closure, their youngest son, Andrew, said after the sentencing.

It also shed some light on what happened inside the farmhouse the night the Stocks died. According to Cox, what happened is this:

Early the morning of April 17, 2006, Reid and Fester pulled into the the Stocks’ driveway and loaded two shotguns in case they encountered dogs or an armed homeowner. They walked to the back of the house, where they looked for a place to enter. Fester found an unlocked window and climbed inside, then let Reid in through a door.

Reid and Fester went upstairs to the room where Wayne and Sharmon Stock were sleeping. Either Reid or Fester turned on a light, and Fester pointed his shotgun and shot Wayne Stock, hitting him in the leg.

Wayne got out of bed and began to struggle with Fester. Fester looked at Reid and asked her to help. She fired her gun. It is unclear whether Reid’s shot killed Wayne Stock or if Fester shot him again.

Sharmon, meanwhile, had woken up. She had the phone in her hand. Someone — Reid wrote in her statement it was Fester — shot her in the face. Sharmon screamed.

Then Reid and Fester fled.

In the statement Rehmeier read in court Monday, Reid wrote that she still thinks about Sharmon Stock’s scream, “a piercing scream that wakes me up often.”

Reid has thought a lot about about that night, said her attorney, Tom Olsen.

During Monday’s hearing, Olsen painted Reid as someone who has changed greatly since her arrest. She has has started attending Bible studies and worked toward her G.E.D., drawing praise from her instructors in both, he said.

She’s cooperated with investigators, Olsen said, and she’s talked about her desire to apologize to the Stocks’ family, coupled with a concern that doing so would be hurtful.

In fact, he said, she was an honor roll student with no criminal history until 2004, when her mother and stepfather divorced. And then she started skipping school, breaking into cars and dating Fester.

“It’s not an excuse,” Olsen said of the divorce. “It’s merely for the purpose of explaining how and why.”

Cox disagreed that Reid had changed, saying she had a history of lying when she saw that she could benefit from doing so.

And then, there’s the matter of the letters.

In a journal entry and a letter to Fester, Reid wrote that she had killed someone and that she had “loved” it.

“She was sprayed with the blood of the victim, and subsequently was able to say she loved it,” Cox said.

Cox described Fester as even more troubled, as someone with an extensive criminal history, including sexually assaulting a younger family member.

Fester has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyper-activity disorder, depression, adjustment disorder, personality disorder, alcohol dependence and transvestite fetishism, Cox said.

“This is a train wreck of a life,” Cox said.

In the end, Rehmeier agreed, saying that protecting society figured into Fester’s two life sentences.

Just before he was sentenced, Fester read from a crumpled piece of paper, his hands shaking.

He said he was sorry, that he felt sorry every day for what he did to the Stocks.

“They are gone, and all I want to do is take that day back,” he said.

Reid didn’t prepare a statement but asked to address the Stocks, too.

“I just want to say I’m deeply sorry for all the pain I’ve caused,” she said, fighting tears.

No one has felt that pain more deeply than Andrew Stock, who discovered his parents’ bodies, who still wakes up in the night and patrols his own home to make sure no one has broken in.

Words can’t describe the past year, said his sister, Tami Vance.

But Andrew Stock and his siblings were relieved Monday when both Reid and Fester received maximum sentences.

“We’re glad that justice was served,” he said.

State v. Reid

274 Neb. 780

STATE OF NEBRASKA, APPELLEE, v. JESSICA M. REID, APPELLANT.

No. S-07-303.

Supreme Court of Nebraska.

Filed January 4, 2008.

Thomas J. Olsen, of Troia & Olsen, for appellant.

Jon Bruning, Attorney General, George R. Love, and Andy Maca, Senior Certified Law Student, for appellee.

HEAVICAN, C.J., WRIGHT, CONNOLLY, GERRARD, STEPHAN, McCORMACK, and MILLER-LERMAN, JJ.

CONNOLLY, J.

Under a plea agreement, Jessica M. Reid pled guilty to two counts of second degree murder for the deaths of Wayne and Sharmon Stock. The district court sentenced Reid to not less than life imprisonment nor more than life imprisonment for each murder. The court ordered Reid to serve the sentences consecutively. Reid appeals, assigning that her sentences are excessive. We affirm.BACKGROUND

Before embarking on this crime spree, Reid and her codefendant and boyfriend, Gregory D. Fester II, were living together in Horicon, Wisconsin. On April 15, 2006, they left Wisconsin. After stealing and abandoning two vehicles, they stole money, a 12 gauge shotgun, ammunition, and another vehicle from a Wisconsin home. They then drove to Iowa, planning to rob a few houses on their way to Arizona. They broke into two more houses in Iowa. They vandalized the first house and stole a .410 shotgun and ammunition and stole about $300 from the second house. Later that night, they decided to burglarize the Stocks’ rural home in Cass County, Nebraska.

Fester entered the first floor through a window and opened a door for Reid. Fester carried the 12 gauge shotgun, and Reid carried the .410 shotgun. Reid stated to law enforcement that they did not stay on the first floor long before heading upstairs. She heard snoring coming from upstairs and removed her coat so she would not make any noise. She then followed Fester upstairs. According to Reid’s account, Fester turned on the Stocks’ bedroom light and then came back into the hallway and asked her what to do. She replied, “do something.” Fester then ran back into the room and shot Wayne Stock in the leg while he was in bed or getting out of bed. Wayne Stock then struggled with Fester over the 12 gauge shotgun. While they were struggling, Reid shot Wayne Stock with the .410 shotgun. She stated that Wayne Stock looked her directly in the eyes and that she then pulled the trigger. She further stated she shot Wayne Stock above his right eye and he fell forward. After Wayne Stock fell, Fester jumped over his body and shot him in the back of the head with the 12 gauge shotgun and then shot Sharmon Stock in the face. According to Reid, she and Fester immediately ran from the house and left in the stolen vehicle, which they later abandoned.

On April 23 and 24, 2006, police arrested Fester and Reid in Wisconsin for vehicle theft. Reid had left an inscribed ring in the Stocks’ home that she and Fester had earlier stolen from the Wisconsin vehicle or home. The ring ultimately connected Reid and Fester to the murders.

During the investigation, law enforcement officers recovered evidence from Reid’s home. On April 22, 2006, 5 days after the murders, Reid wrote in her journal: “I killed someone. He was older. I loved it. I wish I could do it all the time. If [Fester] doesn’t watch it I am going to just leave one day and go do it myself.” Also, at some point while Fester was in jail, Reid wrote a letter to him and left it at the home, apparently for him to retrieve after authorities released Fester on the Wisconsin charges. The letter was left in a cigarette box, which also contained a spent 12 gauge shell casing from the murders. In the letter, she wrote: “And this bullet well bunny it’s the only thing left. And I loved it, but that’s something we will talk about one day. But it’s here also bcuz [sic] that was something I did for you, me and for you to love me as much as I love you.”

On June 10, 2006, a Wisconsin detective interviewed Reid about the murders. During the interview, Reid denied that she shot Sharmon Stock but admitted that she shot Wayne Stock. On August 28, the State filed an information charging Reid with two counts of first degree murder in the Stocks’ deaths. In exchange for her guilty pleas and agreement to testify against Fester, the State agreed to amend the information to two counts of second degree murder.

STATE v. FESTER II

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Fester lived with his girlfriend, Jessica Reid, in Horicon, Wisconsin. Fester and Reid left their apartment in Wisconsin on April 15, 2006, and arrived in Nebraska on April 17. Along the way, Fester and Reid participated in a crime spree that involved, among other things, stealing two cars and burning another, breaking into several homes, and stealing a 12 gauge shotgun and ammunition.

On the night of April 17, 2006, Fester and Reid arrived in Murdock, Nebraska, and, armed with a 12 gauge shotgun and a .410 shotgun, broke into the home of the Stocks with the intent to burglarize the home. The Stocks’ home had been randomly selected. After entering the house, Fester heard snoring coming from upstairs. Fester and Reid went up the stairs toward the Stocks’ bedroom.

It is not entirely clear what happened when Fester and Reid reached the Stocks’ bedroom. But according to the uncontested recitation of the facts offered by the State at the sentencing hearing, Wayne Stock attempted to confront Fester and Reid, and Fester fired a shot that hit Wayne Stock in the knee. A struggle ensued between Fester and Wayne Stock. Apparently, while Fester and Wayne Stock were allegedly fighting over the weapon, Fester told Reid to “do something,” and Reid fired her .410 shotgun in the direction of Wayne Stock. Fester then shot Wayne Stock in the back of the head with his shotgun, killing him. Then, Fester entered the bedroom and shot Shannon Stock in the face, killing her.

Pursuant to a plea agreement, Fester was eventually charged in an amended information with two counts of murder in the second degree 1 and one count of use of a firearm in the commission of a felony.2 Fester pled guilty to all three counts of the amended information.

The presentence investigation report revealed that Fester was 19 years of age at the time the Stocks were killed and that at the time of sentencing, he had a 2-year-old child. Fester had a lengthy history of substance abuse, including the use of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and dextromethorphan. Fester also has an extensive history of criminal activity. Fester’s prior criminal activity included, among other things, trespass to land, shoplifting, disorderly conduct, theft from a motor vehicle, criminal damage to property, and sexual assault. The presentence investigation report also revealed that during Fester’s life, he had been under various degrees of psychiatric care and had taken a variety of psychotropic medications.

Following a sentencing hearing, the district court sentenced Fester to a term of not less than life imprisonment nor more than life imprisonment for each count of murder in the second degree and a term of 10 to 20 years’ imprisonment for use of a firearm to commit a felony. The sentences were to be served consecutively. Fester appealed.

Case shut, questions linger about investigators in Murdock murders

LINCOLN — The dirty cop acted alone.

That’s the explanation a top state official gave in blaming David Kofoed for a 2006 murder investigation that accused the wrong people. After all, Douglas County’s one-time CSI miracle worker was convicted of planting blood in the case.

Yet two Nebraska State Patrol investigators and two Cass County sheriff’s deputies were named along with the disgraced CSI chief in the same federal lawsuits.

It has been eight years since Wayne and Sharmon Stock were slain in their rural Murdock, Nebraska, home by shotgun-wielding teenagers on a drug-fueled crime spree. The criminal case is closed, the lawsuits are over, and the killers sit in prison.

Still, a mystery lingers: If the four investigators other than Kofoed did nothing wrong, why did their employers agree to a nearly $2.5 million settlement?

Agency leaders and their attorneys declined repeated requests to talk about the settlement, the investigation or whether the case has prompted changes to avoid similar problems. Rather, they stressed that the final terms required no admission of wrongdoing. Two of the four officers, meanwhile, continue to work as investigators.

So The World-Herald dug into a massive digital archive of court records for answers. The review turned up what an appeals court described as circumstantial evidence that at least some of the other investigators conspired with the CSI chief to falsely implicate cousins Matthew Livers and Nicholas Sampson.

Lawyers for the investigators twice failed to convince federal courts to dismiss the conspiracy claim and other civil rights violations alleged in the lawsuits. Last October, as the case was settled, an Omaha jury was days away from hearing accusations that:

» Two State Patrol investigators and a deputy engaged in constitutionally prohibited coercion when they interrogated Livers. As a result, Livers made a false confession that also implicated Sampson. The state’s own interrogation expert said under cross-examination that the questioning of Livers was flawed.

» The investigators fabricated evidence by feeding crime scene details to Livers during the interrogation and using coercion to produce incriminating statements from other witnesses. There also was disputed evidence that the video of Livers’ recantation, made the day after he confessed, was withheld from the prosecutor.

» The investigators and the crime lab commander engaged in a conspiracy against the cousins. Two of the investigators pressured CSI technicians to find some physical evidence to bolster Livers’ confession, and one of the patrol investigators spent more than three hours at the Douglas County crime lab the same day Kofoed “found” a victim’s blood in the car.

» The investigators arrested Livers without probable cause.

Lawyers for the patrol and Cass County vigorously defended their clients and denied all allegations in legal filings leading up to the trial.

They contended that the investigators had compelling reasons to focus on Livers, which included evidence of serious conflicts with the murder victims, who were his aunt and uncle. They insisted the interrogation was not out of bounds.

They also said the investigators were assured by the lead prosecuting attorney that the confession constituted probable cause for the warrantless arrests of Livers and, hours later, Sampson.

While the settlement requires the Sheriff’s Office to seek specialized interrogation training, there was no such requirement for the State Patrol. And the patrol investigators refused a request from Livers for a public apology, saying they still believe he played some role in the murders.

As for a conspiracy, the law enforcement agencies argued the plaintiffs failed to produce concrete evidence of actions taken by any of the four investigators to help plant the blood.

In fact, in the months after the cousins were charged, the officers helped arrest the Wisconsin teens responsible for the crime, Kim Sturzenegger, the attorney representing Cass County, wrote in a trial brief.

“Because the investigators were determined to follow up on all leads and conduct a thorough investigation, they developed the information which ultimately led to the decision to drop charges” against Livers and Sampson, she wrote.

That’s how it ended.

At the beginning, investigators locked on the man they were convinced was the killer.

The investigation

Wayne Stock, 58, farmed and ran a successful hay business. Sharmon, 55, was a teacher’s aide who also operated a cake business from her home. The couple were widely known and well-liked in Murdock, a community of 270 people about 40 miles southwest of Omaha.

Their murders shocked everyone who knew them.

The bodies were discovered about 9 a.m. on April 17, 2006, the day after Easter Sunday, in the upstairs master bedroom of the two-story house. The case fell under the jurisdiction of Cass County Sheriff Bill Brueggemann, but because homicides in the county were rare, he sought help from the State Patrol and Douglas County CSI.

Investigators recovered important evidence from the scene, including live and spent shotgun ammo, a marijuana pipe and a small flashlight they suspected had belonged to the killer. Later they also found a ring determined to have been left behind. Otherwise, the house was not ransacked, and it appeared no cash or other belongings were missing.

A criminal profiler for the patrol said the point-blank shots and lack of stolen property indicated the intruder came with the intent to kill. And blood spatter on a wall revealed more than one person had been involved.

The profiler said to look for two young males.

Patrol Investigator William Lambert and Cass County Sheriff’s Investigator Earl Schenck Jr. were assigned primary roles in the case. Though experienced criminal investigators, neither had previously headed a homicide inquiry.

Along with Sheriff’s Sgt. Sandra Weyers, the investigators started by interviewing family members, asking if they knew anyone who would want to hurt the couple.

Several relatives said Matt Livers had a history of conflict with his aunt and uncle, including friction over the future inheritance of a home belonging to Wayne Stock’s mother. Livers had lived with his grandmother for a period, and his aunt and uncle had reportedly insisted he move out.

Relatives also described Livers, 28, as slow, different and immature for his age.

The oldest son of Wayne Stock’s sister, Livers was diagnosed as learning disabled and took special education classes through school. Although he had no prior criminal record, he struggled to keep employed as an adult.

A psychological assessment conducted months after his arrest listed his IQ at 68, which categorized him as mildly mentally retarded. The report also concluded his verbal abilities are significantly higher than his overall intellectual performance, “perhaps leading one to believe, (e.g., in conversation) that he is more highly functioning than he truly is.”

Late at night on April 17, Investigators Lambert and Schenck conducted their first interview of Livers. He indicated there was a past tiff with his relatives, but all had been forgotten.

In the meantime, the investigators identified a vehicle they believed was used by the killers. A Ford Contour, which belonged to a cousin of Livers, matched the color of a vehicle seen by witnesses near the Stock home the morning of the killings. As it turned out, the cousin’s car also had been detailed just hours after the shootings occurred.

On April 19, the car was towed from Lincoln to Omaha, where it was searched by members of the CSI team for six hours, to no avail. They also tested vacuum bags recovered from the detail shop, which produced no traces of blood or DNA.

On April 20, Lambert gave Livers a ride to Omaha so he could submit fingerprints and a DNA sample. Then, on April 25, Lambert and Schenck picked up Livers at his rental home in Lincoln and drove about 50 miles to the Sheriff’s Office in Plattsmouth.

They sat down in an interview room, turned on the video camera and started asking questions about 9 a.m.

Livers told investigators he had spent much of Easter at a gathering hosted by his grandmother, Lorene Stock.

He returned home to Lincoln about 5:30 p.m. and said he stayed at the house until he went to bed that night. He said he slept the entire night next to his fiancee, Sarah Schneider.

About 1:30 p.m., saying he wanted to clear his name, Livers submitted to a lie-detector test. Patrol Investigator Charlie O’Callaghan, who was working toward certification as a polygraph examiner, told him he failed.

The results were infallible, O’Callaghan said, and they could only mean Livers killed his relatives or knew who did. Livers admitted to being nervous while taking the test, but he vehemently denied he killed the couple.

About 2:30 p.m., Investigators Lambert and Schenck returned to the interview room. The tone of their voices changed as they bombarded Livers with accusations.

Lambert told Livers his reactions to the polygraph questions provided conclusive proof that he killed the Stocks. Livers, visibly shaken, protested. In the span of seconds, the patrol investigator swatted away eight denials in a row.

“Listen to me and listen well,” Lambert said. “This is a chance to save yourself. This is potentially a death sentence. No lie, OK? If you are involved in this, then you can save yourself now.”

And the only way for Livers to save himself, the investigators said, was to declare his guilt.

Still Livers tried repeatedly to convince the officers he was innocent. The patrol investigator said many people in similar positions have tried and failed to outsmart authorities.

“I’m dumb as a brick,” Livers replied.

At another point, Schenck asked if Livers considered himself a man. Livers nodded.

“Then stand up,” Lambert said.

Livers stood, taking the officer literally.

After more Livers denials, Schenck raised the stakes.

“If you don’t admit to me exactly what you’ve done, I’m going to walk out that door and I am going to do my level best to hang your ass from the highest tree,” he said. “You are done. I will go after the death penalty. I’ll push and I’ll push and I’ll push and I will do everything I have to make sure you go down hard for this.”

The investigators then scripted their theory of a motive, telling Livers he was sick of being put down by his aunt and uncle, tired of seeing their wealth while he struggled on the edge of poverty. They suggested it was understandable if he snapped and lashed out.

After more accusations, Livers said: “I’m not this kind of person. All I remember is sleeping in my bed that night.”

Finally, after about 6½ hours of questioning, Livers started to agree with his accusers.

“The truth is, you got a gun. Right or wrong,” Schenck asked.

“Right.”

“And you took that gun back to your Uncle Wayne and Aunt Sharmon’s house, right?”

Livers paused.

“Right or wrong? Come on, Matt.”

“Right.”

At first he took sole responsibility for the killings. But after a lengthy series of questions posed by Schenck, he implicated his cousin, Sampson, the brother of the man whose car had been seized. Livers also said he and Sampson used the Ford Contour.

Authorities arrested Livers and his cousin that night.

The next day, facing another polygraph exam, Livers recanted in full.

“I’ve been just making things up to satisfy you guys,” he said, “and answering questions just from, you know, basically fitting an answer to what you guys have been asking.”

Sampson, 21, agreed to undergo a lie-detector test of his own. After he was told he failed, however, he refused to answer more questions without a lawyer.

Then, two days after the confession, CSI commander Kofoed searched the Ford Contour a second time for gunshot residue. Kofoed, who had made incredible DNA discoveries in past homicide investigations, did it again. He said he found a speck of blood underneath the dashboard. Tests later confirmed it was Wayne Stock’s blood.

In the months that followed, Livers and Sampson sat in jail, facing a trial and a possible death sentence for a double murder. Authorities tested their clothing, firearms and other belongings, but found nothing else to physically connect the men to the crime scene.

Tests on the marijuana pipe and ring did produce DNA, but not a match with Livers and Sampson.

An inscription inside the ring, however, led authorities to its owner in Wisconsin. They soon learned the ring had been inside a pickup that had been stolen on Easter Sunday by Gregory Fester, 19, and Jessica Reid, 17.

Lambert and Schenck drove to Wisconsin to interrogate the new suspects. The two confessed, each blaming the other for shooting the victims.

But the investigators kept after the teens, telling them accomplices from Nebraska had to be involved. Under questioning that included threats of the death penalty, the teens amended their stories, saying they were led to the Stock home by two men they met in Murdock. When shown photos, however, Reid picked an image of Sampson but not Livers. Fester picked out two photos, neither of which was of Livers or Sampson.

In a subsequent interview, Reid recanted and said she and Fester were the only ones present. They picked the Stock house at random. DNA matched Fester and Reid, and authorities recovered matching shotgun shells, bloodstained clothing and a diary entry by Reid describing a murder.

Each pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, and each was sentenced to life in prison.

Sampson was released from jail after six months. Livers got out after more than seven months. Charges against both were dropped.

After their release, the cousins filed civil rights lawsuits against the authorities.

The lawsuits named Lambert and O’Callaghan from the State Patrol, Schenck and Weyers from the Sheriff’s Office and Kofoed from the CSI unit, along with Cass County, Douglas County and Douglas County Sheriff Tim Dunning.

Dunning eventually was dismissed from the lawsuits, and he wrote a public apology to Livers. Douglas County reached settlements, agreeing to pay Livers $50,000 and Sampson $75,000.

The rest fought on.

The interrogation

To win on their first claim, the plaintiffs sought to prove Lambert, O’Callaghan and Schenck coerced a confession in a manner that “shocked the conscience.” That means they had to prove a higher standard than simple negligence.

When it comes to interrogating suspects, however, the courts generally have given law enforcement plenty of leeway. For example, interrogators can lie and deceive, making claims to have fingerprints or other incriminating evidence that does not exist.

A primary responsibility for law enforcement is to make sure suspects know they have a right to an attorney and to refuse police questions. Officers met the standard with Livers, who never asked for a lawyer.

In addition, the U.S. Supreme Court has said a suspect must confess voluntarily in order for the statements to be admissible. Coercion, defined as overbearing a suspect’s will, violates an individual’s 14th Amendment right to due process.

The courts generally have considered the “totality of the circumstances” when deciding if a confession was coerced. The circumstances include police actions, whether the confession is corroborated by other evidence and the mental fitness of the suspect being questioned.

Judges have ruled interrogators can’t obtain confessions with physical force, threats of harm or promises of leniency. But, as anyone knows from watching a season of “Law & Order,” interpretations of what’s a threat or promise can vary from case to case.

The courts have thrown out confessions resulting from interrogations that contained a combination of excessive length; withholding of food, water or sleep; and keeping suspects in a physically uncomfortable setting. They also examine confessions for “contamination,” when investigators feed crime-scene details to a suspect that only a killer would know.

The Livers interrogation bore striking similarities to a 2001 Missouri case in which the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out a confession on the grounds that police shocked the conscience.

In that case, the judges determined police coerced an intellectually disabled man when they interrogated him for more than four hours, falsely claimed to have incriminating evidence, ignored his protests of innocence and used leading questions that provided details from the crime scene.

Livers had not eaten before police picked him up and was not given a meal until after the 11-hour interrogation. On tape, he frequently complained of the “freezing” temperature in the interview room.

Officers ignored more than 80 denials, and questioned Livers for about 6½ hours before he confessed. Some examples of “contamination” included investigators revealing where the victims were shot, the location of their bodies and Sharmon Stock’s apparent attempt to phone for help.

Attorneys for the investigators argued they did not know Livers was intellectually disabled. They apparently did not look into his educational history, and the IQ test wasn’t done until months after the confession.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs said the investigators had been told by relatives Livers was “slow.” They also brought up Livers’ description of himself as “dumb as a brick” and how he took literally the challenge to “stand up” and accept responsibility for his actions.

The investigators argued Livers and Sampson failed to meet the necessary standard to win the claim.

Quoting from a previous ruling by the 8th Circuit, they said there must be “a violation of rights so severe, so disproportionate to the need presented, and so inspired by malice or sadism … that it amounts to brutal and inhumane abuse of official power literally shocking to the conscience.”

Manufacturing evidence

The undisputed example of evidence manufacturing in the case was Kofoed’s planting of blood in the tan Ford Contour. In a separate criminal case in 2010, Kofoed was convicted of evidence tampering for planting the blood in the Contour. He served two years in prison.

But the cousins argued the interrogators fabricated evidence by leaking crime scene details so Livers could fashion a more believable confession. Lambert and Schenck also used leading questions to help Livers shape his statements.

Another element of the false evidence claim was that Lambert and Schenck threatened, coerced and manipulated the Wisconsin teens into incriminating the cousins. Investigators Weyers and O’Callaghan allegedly did the same with a close friend of Livers, an intellectually disabled man in Texas whom Livers had visited in the weeks before the murders.

In addition, the tape of Livers recanting the confession was not turned over to his defense attorney for six months, prompting an official complaint against the prosecutor.

In a deposition, Cass County Attorney Nathan Cox, the prosecutor in question, said he did not know about Livers recanting, nor was he given the recording until after he had dropped charges against Sampson. The investigators, however, said they turned it over, and suggested Cox must have lost it.

To counter the evidence fabrication claim, the investigators said they never quit following leads in the case. While some of the evidence they developed may have incriminated Livers and Sampson, some didn’t.

“It was their investigation that led to the Wisconsin perpetrators of the crime,” Sturzenegger, the attorney hired by Cass County, wrote in a trial brief. “Their actions ultimately exonerated (Livers and Sampson).”

Conspiracy

In general, Livers and Sampson alleged that all of the investigators conspired to violate their civil rights by their actions in the case. But they focused on the planted blood.

In depositions, Lambert and Schenck each said he made multiple visits to the Douglas County crime lab to check on analysis of the evidence. One of the lab technicians referred to the investigators as “pains” because of their repeated requests for testing and results.

On April 27, two days after the confession, Lambert called Kofoed and asked him to reprocess the Contour, though it had been examined by the CSI team days before. That afternoon, Kofoed and another CSI officer processed the car a second time, and Kofoed said he found blood under the dash.

Entry log records show Lambert signed in at the crime lab at 8:05 p.m. on April 27 and remained there until 11:20 p.m. He returned to the lab the following day. In deposition testimony, he said he could not recall what he and Kofoed discussed other than the blood finding.

Despite the significance of the discovery, Kofoed did not write a report about the blood or even seek to have it tested to see if it came from a victim. Rather, he said he left the swab in the evidence room and forgot about it.

On May 4, investigators learned the DNA recovered from the ring and marijuana pipe found at the crime scene did not match Livers or Sampson. The next day, Schenck arrived at the crime lab and stayed for an undetermined amount of time, but later testified he couldn’t remember why he stopped or to whom he spoke.

Days later, Kofoed wrote a false report claiming he had made the blood discovery on May 8, not on April 27. He transferred the swab for testing, and it came back as a match to Wayne Stock.

It would represent the only physical evidence to tie Livers and Sampson to the crime.

The conspiracy theory relies on “speculation and conjecture,” the investigators argued in legal documents.

“Livers has simply named all the individual defendants as being involved in the conspiracy without stating which defendant did what or who they conspired with to violate Livers’ rights,” Ryan Post, an assistant attorney general, wrote in a trial brief.

In addition, in late 2007, Lambert took a confidential statement from one of Kofoed’s CSI technicians with whom Lambert had formerly worked. The informant accused Kofoed of planting the blood in the Contour. Lambert relayed the allegation to the FBI.

In response, the FBI sought out the informant and eventually started investigating the CSI commander.

Probable cause

The final claim involved the Fourth Amendment requirement that probable cause must exist to support an arrest.

Livers’ attorneys argued their client had been arrested at one of three points: when the investigators picked him up on the morning of April 25 and drove him to the Sheriff’s Office, when they placed him in a windowless interview room, or when Lambert told Livers he could not leave after he allegedly failed the polygraph test.

All three points occurred before Livers confessed. In depositions, the officers agreed their suspicions of Livers did not amount to probable cause until Livers actually confessed.

The state’s attorneys argued their clients should not be found liable for false arrest for any time beyond Livers’ confession. So, at most, the patrol would be liable only for the 6½ hours Livers spent under questioning before his confession.

The investigators also testified they were told by the prosecuting attorney the confession provided probable cause for the arrests. And they pointed to a 2006 ruling in Sampson’s criminal case, in which a district court judge said the confession provided sufficient probable cause for officers to act.

The courts

In 2011, lawyers for the investigators asserted the defense of qualified immunity and tried to get the lawsuits dismissed from U.S. District Court in Omaha. Qualified immunity shields law enforcement officers from civil liability when they perform their duties reasonably and believe they are operating within the law.

To overcome the defense, attorneys for Livers and Sampson had to convince the judge that their rights were violated and those rights were clearly established at the time the investigators acted, Chief U.S. District Judge Joseph Bataillon wrote.

The judge explained that at that stage in the process the law required him to view the facts in the light most favorable to Livers and Sampson. He ruled in their favor.

The investigators appealed to the 8th Circuit. In late 2012, a three-judge panel of the appeals court dismissed the Douglas County sheriff from the lawsuits. As for the rest of the defendants, the panel decided a jury should hear the case. The judges also found evidence of a meeting of the minds to incriminate Livers and Sampson.

In the wake of the legal setbacks, the state tried once more to limit the liability for the patrol’s investigators. This time they argued the confession was credible because Livers provided three crime-scene facts that had not been fed to him by the interrogators.

One was the statement that Wayne Stock was trying to crawl to an office near his bedroom after he was shot in the knee. The others were the color and location of a car parked near the Stock home, as reported by newspaper carriers.

Livers’ legal team said information about the knee wound had been told to Livers by his father, who learned about it from other relatives at the Stocks’ funeral. As for the car’s color, Livers knew his cousin’s vehicle had been seized by police. And the location of the getaway car? It was either up or down the road that ran alongside the farmstead, so Livers simply guessed.

“It’s unbelievably, screamingly obvious Matt Livers had no idea what he was supposed to say, what he was supposed to have done, and he was guessing and following cues from Schenck and Lambert,” said his attorney, Locke Bowman, who also directs the MacArthur Justice Center at the Northwestern University School of Law.

When the litigation ended on the brink of the jury trial, Attorney General Jon Bruning said his office made an economic decision to settle rather than risk paying greater damages. Then he blamed the “dirty cop.”

“This case was just poisoned by Kofoed’s planting of evidence,” he said. “We felt we had no choice but to settle.”

The troopers, Bruning said, “acted honorably.”

More recently, the attorney general has declined requests to discuss in detail the claims made against the troopers and deputies.

Lambert and O’Callaghan remain with the Nebraska State Patrol as investigators; however, Deb Collins, the agency’s spokeswoman, wouldn’t provide specifics on their assignments.

“The case was settled with no admission of wrongdoing by the State of Nebraska, and we continue to stand by our personnel,” Patrol Col. David Sankey said in an email response to an interview request.

In a 2009 deposition, Lambert said he still considered Livers guilty based largely on the polygraph results. And he was adamant that his interrogation and other actions remained within legal parameters.

“Let’s just say I would not change anything about the case that I did,” Lambert said.

Lambert said in his opinion, none of the interrogation threats were coercive. He argued a threat has to be carried out for it to be coercive.

He bristled at suggestions that his colleague’s “hang you from the highest tree” statement was out of bounds.

“This is heinous,” Lambert said. “You’re not going to sit down with Matt Livers and pat him on the back and say ‘Listen, Matt, we need to talk, OK? You’re in a little bit of trouble here, buddy. These are the facts, now come clean.’ ”

Lambert said the patrol had given him little specialized training in interrogations. Anything beyond what he learned as a criminal justice major at the University of Nebraska at Omaha or the patrol’s academy came through experience.

In his deposition, polygraph examiner O’Callaghan disagreed with a paid expert who said the trooper’s execution of the test was so flawed it could not be accurately scored. The expert also said the results were inconclusive rather than showing deception by Livers.

Meanwhile, the $2.48 million settlement came from state coffers and a risk-management pool mostly funded by county governments.

Part of the settlement required Cass County sheriff’s investigators to undergo training on the interrogation of learning disabled or mentally ill suspects, said Maren Chaloupka, the Scottsbluff attorney who represented Sampson in the lawsuits.

Sheriff Brueggemann referred questions to the private attorneys hired to defend the investigation. They, in turn, declined to discuss the case.

In a 2009 deposition, Deputy Schenck said he did not consider any statements he made during the interrogation to be improper. He rejected suggestions that his goal was to obtain a confession.

“Our approach was to confront him about the answers that he had failed on the polygraph and try to elicit the truth from him,” Schenck said.

Schenck said he asked to be transferred to courtroom security and inmate transport duties after his investigation of Livers and Sampson unraveled. On July 24, 2010, he was arrested and charged with driving under the influence of alcohol in Keith County. He resigned from the Sheriff’s Office four days later.

Since then he has been cited three times for driving under suspension and is no longer working in law enforcement. He did not return messages left with relatives seeking comment for this story.

Weyers also left the Sheriff’s Office, and now works as Cass County’s emergency manager.

Experts on police interviews, including one hired to help defend the state, said they are troubled by what occurred in the Livers interrogation.

Stan B. Walters of Versailles, Kentucky, has been training law enforcement officers for 30 years — including Deputy Schenck and other officers in Nebraska — to read body language and conduct interviews. The state brought in Walters to review the Livers interrogation. Ultimately he came to see the confession as “probably false” and the techniques used to obtain it as flawed, he said in an interview.

But Walters also argued some of the tactics are similar to what he has seen in scores of interrogations across the nation.

“The general technique, unfortunately, was not uncommon,” he said. “What I saw was not an aberration.”

Jim Trainum, a former Washington, D.C., homicide detective who now works as a consultant for law enforcement agencies, said he uses portions of the Livers interrogation to teach how to avoid false confessions. He argued Nebraska law enforcement agencies should learn from the Livers tapes.

The stakes are high: Not only do false confessions accuse the innocent, they can allow the guilty to remain free, Trainum said.

The Nebraska Law Enforcement Training Center in Grand Island uses the Livers interrogation to show what police should do, and not do, to ensure confessions are legal. In particular, the case is used to help trainees learn how to recognize signs a suspect is cognitively impaired, said William Muldoon, the center’s director.

The training center serves all Nebraska agencies except the patrol and the Omaha and Lincoln Police Departments.

Several experts who reviewed the interrogation were most troubled by the amount of crime scene information the investigators provided to Livers before and after he confessed.

Krista Forrest, a psychology professor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney who has researched and written about police deception during interrogations, said the confession lacked a key factor that damaged its credibility: At no point was Livers able to give an unprompted retelling of the killings that closely matched the crime scene evidence, she said. Nor did he provide investigators with the location of the murder weapon, bloodstained clothing or some other piece of evidence they lacked.

“Honorable police work?” she said. “To blame this on Kofoed alone is to ignore a big part of everything that went wrong.”