Victim: Matthew Foley, 16

Age at time of murder: 17

Crime location:

Crime date: November 21, 1996

Crimes: Armed robbery & murder

Weapon: Firearm

Murder method: Gunshots to the head

Murder motivation: Robbery

Convictions: Reckless manslaughter & robbery, which together made it felony murder

Sentence: Life without parole (LWOP) and then re-sentenced to 42.5 years

Incarceration status: Incarcerated at the Fremont Correctional Facility & has a parole hearing in May 2031

Summary

Jones organized a scam in which he would meet Matthew to sell him a gun, and then take the weapon back to show how to load it. Then he would rob Matthew at gunpoint and leave. However, Jones ended up shooting Matthew in the head as well, killing the 16-year-old. Jones was found guilty of felony murder and sentenced to LWOP. His sentence was later reduced to 42.5 years.

Details

Felony murder: “legal fiction”?

It began with a simple plan: Trevor Jones would scam a kid out of $100 and then just walk away.

But the night of Nov. 21, 1996, ultimately revolved around a loaded gun. Jones, 17, fired a single shot – accidentally, he claims – that struck 16-year- old Matthew Foley in the head and killed him.

The incident devastated two families, sent Jones to prison for life without parole and left Denver jurors questioning a felony murder sentence they found too harsh – and at odds with their findings about the shooting.

In Colorado, 60 percent of the juveniles sentenced to life without parole since 1998 mark time in prison because of felony murder convictions. Fewer than one-fourth of adults serving life sentences for crimes during that same period are in prison on that charge.

The disparity surprises neither defense lawyers nor researchers on juvenile development. Colorado is one of only 14 states with a combination of three controversial laws: prosecutors’ direct-file discretion, which allows them to circumvent the juvenile system and move directly to adult court in some crimes; the crime of felony murder, which can apply to anyone involved in certain crimes in which an innocent party dies; and life without parole for juveniles.

Prosecution tools that can hold several individuals responsible in homicide cases inordinately ensnare young offenders, says Laurence Steinberg, director of the Philadelphia-based MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Adolescent Development and Juvenile Justice.

“It’s not only because of kids’ propensity to commit crimes in groups,” he says, “but also because of the developmental differences that make kids more susceptible to peer influence.”

Andrew Heher, who represented Jones on appeal, calls felony murder a “legal fiction,” a murder charge predicated on an entirely different crime – in this case, robbery.

“Felony murder is unnecessary and outdated because it doesn’t allow for an accurate determination of culpability,” Heher says. “It’s unfair because it does not particularly reflect factually how this case played out, the course of events that led to the death of the victim and what transpired before the shooting occurred.”

But backers of felony murder prosecutions counter that a life- without-parole penalty can deter criminals.

“It gives the message: If you’re going to be involved in criminal activity and death occurs, know upfront you’re going to be nailed,” says former Weld County District Attorney Al Domin guez, who held that job for 16 years.

Felony murder, found in the majority of states but with varying degrees of punishment, has been around since Colorado became a state – and long before that in English common law. It holds defendants liable for first- degree murder if they commit or attempt certain felonies, such as burglary or robbery, and someone dies “in the course of or in furtherance of the crime,” according to the law.

It departs from other legal descriptions of murder that take into account the accused’s state of mind, and allows defendants to be charged with deaths caused by others.

Notes Steinberg: “I doubt when the statutes were written that they were intended to be used to take 15-year-olds who happened to be hanging around and sentence them to life without parole.”

Trevor Jones was no bystander in Matthew Foley’s death; accidentally or not, he pulled the trigger. But the jury’s eventual finding in the case illustrated another quirk of felony murder law: It can blur a jury’s determination of events.

Gun buy gone awry

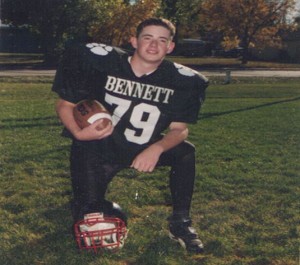

Foley, 16, had agreed to buy a handgun for a cousin who persuaded him to make the illegal purchase. Foley contacted Jones, a schoolmate from the Eastern Plains town of Bennett.

Jones knew another teen who had recently acquired a handgun. And he saw an angle.

He could sell the gun to Foley for $100 and then take the weapon back under the pretense of explaining how to load it. Then he would leave with both the money and the gun, because Foley couldn’t report the scam without admitting his own attempt to illegally buy a gun.

But that’s not what happened.

After a day of smoking marijuana, drinking, watching TV and tossing a football, Jones and his friend met Foley and one of his buddies that night and drove to a Denver apartment complex, according to court testimony.

Around 8:30 p.m., as the four teens sat in the car driven by Foley’s friend, Jones handed the gun from the back seat to Foley in the front passenger seat. Foley passed Jones a $100 bill.

Jones then asked for the gun – ostensibly to show Foley how to load it. He slid the magazine into the grip and pulled back the slide on top of the weapon to chamber a round.

“What’s up now, b—-?” Jones said.

Suddenly, he got out of the car with the gun and the money and then moved toward the front passenger window.

“You better not say anything or this’ll come back on you,” he told Foley.

The 9mm Taurus discharged, and the bullet entered the car through an inches-wide gap in the partially opened window. It hit Foley near his right temple.

Foley’s friend, sitting in the driver’s seat, saw Jones turn to run, then stop and peer inside the front passenger window, looking surprised.

Jones and his friend ran into the apartment complex. Foley’s friend pulled out of the parking lot and headed to a nearby convenience store, where he sought help.

Foley died that night.

Jones hid out in a shelter at Cherry Creek State Park, he says – too frightened to go home or answer his parents’ electronic pages. The next morning, he learned about Foley’s death in the newspaper. That afternoon, he turned himself in to Denver police.

“I figured I’d go to prison for 20 years or something,” he says now. “I figured they’d realize it was an accident, but I had to go deal with what I’d done. When I was taken to Denver city jail, the attorneys explained what felony murder was. That’s when I realized the gravity of the situation.”

The teen who had provided the gun that killed Foley cut a deal with the prosecution. He pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit aggravated robbery – but in juvenile court, avoiding the lengthy mandatory sentence he could face in adult court. In return, he testified against his best friend.

Although the prosecution charged Jones with first-degree murder, the jury came back with a guilty verdict on the lesser charge of reckless manslaughter.

An accompanying robbery count proved a tougher call. The defense argued that Jones had committed theft, because the plan involved no force, threats or intimidation. Some early support for that position waned, and ultimately jurors pegged the crime as robbery.

That sealed Jones’ fate.

A felony murder conviction followed because Foley had died during the robbery, and Jones received a mandatory life sentence without possibility of parole.

“A tough-guy image”

In the visiting room at the Limon Correctional Facility, Jones, now 26, can’t pinpoint any one thing that turned him into the kind of teen who found himself the defendant in a murder trial.

He says he absorbed the worst elements of popular culture and embodied the worst possible result. In music, movies and, eventually, friends, Jones embraced the extremes to his parents’ dismay and his own delight. His grades suffered, he dabbled in drinking and drugs, and he got into fights.

“The only term I can think of would be like a thug,” he says now. “I enjoyed the image. It was a tough-guy image, but more overall I was trying to be cool. But I’m not going to blame the influences around me as the source of my evils. I just gravitated to that for some reason.”

After Jones’ arrest, his family disintegrated.

Jack and Patty Jones’ marriage of 28 years went on the rocks. Both sank into depression and drank, and they divorced. Jack lost his aviation business and eventually opened an auto oil and lube shop in Lakewood. Patty moved back to Oklahoma.

Jennifer Jones – 19 at the time of the crime – also reached a life-changing moment. During her brother’s appeal, she listened to a lawyer for the state argue that while the shooting may have been a tragic accident, “the law’s the law.” In those words, she found a new purpose.

In May, she’ll graduate from the University of Denver law school, burdened by massive student loans but buoyed by the idea of becoming a public defender.

“It’s a way of coping,” she says, “to try to do something positive.”

Foley’s parents, Gail and Wayne Palone, also have used positive action as a coping tool.

Every September since their son died, they have held an auction and dinner to raise money for college scholarships delivered in his name.

Applicants must write an essay on how to prevent teen violence.

But their son’s death also tore at the family in ways that only began with grief.

Although the Palones never believed that Jones fired the shot accidentally, they reserve a separate disdain for Foley’s cousin, whose desire for a handgun sucked their son into the incident.

“He’s no longer part of this family,” says Gail, the youngest of eight siblings.

She struggled with depression. She and Wayne went to two meetings of Parents of Murdered Children but felt overwhelmed. They sought private counseling. Gail’s dad, who felt the loss of a friend as well as a grandson when Foley died, went with them.

Foley’s parents remember him as a 16-year-old kid with a soft heart – a kid who once decided to forgo the mountain bike he craved for Christmas so the money could provide gifts for needy children.

The family had moved from Northglenn to about 40 acres on the Eastern Plains as Foley turned 14. At his previous school, shell casings had been found in a locker room, prompting Gail and Wayne to seek a smaller, safer community.

Foley never excelled in class but dreamed of attending the University of Notre Dame and becoming a sports journalist. On their sprawling property, Wayne responded to his son’s affinity for baseball by constructing a backstop and field just outside their door. Foley half-joked about planting corn beyond the outfield to create his own “field of dreams.”

Now, Gail and Wayne open the mailbox to wedding or birth announcements from his classmates, bittersweet reminders of what they’ve missed. Songs play on the radio. Favorite TV shows air. Credit-card applications arrive in the mail addressed to Matthew Foley.

“He was a good kid – happy,” says Gail. “He always had a smile on his face.”

“We followed the rules”

Jones appealed his case on the grounds that he couldn’t be convicted of both reckless manslaughter and felony murder for Foley’s death. All parties agreed that one conviction or the other had to be thrown out.

A three-judge appeals court panel, which convened in Boulder at the University of Colorado’s law school, voted unanimously to toss the manslaughter conviction and keep the felony murder conviction with its life sentence.

The appeals court sought to “maximize the effect of the jury’s verdict,” in the words of a previous legal decision, by giving weight to the convictions that carried the harshest sentences.

But three of four jurors contacted recently say the court’s ruling betrayed their findings. The fourth questioned a life sentence that allowed no consideration for parole.

Martin Caplan, who served as foreman of the jury, learned the severity of Jones’ sentence shortly after the trial and has struggled with it since.

“I think I always was the kind of person who likes to follow the rules, and we followed the rules in that trial,” recalls the 64-year- old former school headmaster and math teacher. “I don’t know if it’s just my getting older or some of the things I see in our country lately, but part of me feels that now I don’t know whether we should have followed the rules or just done what’s right.”

Given the chance to deliberate again, he says, he would probably find Jones guilty of theft, rather than robbery, to sidestep what he regards as an unfair felony murder sentence.

Juror Jill Fruhwirth, a 46-year- old preschool teacher, doesn’t have an issue with the life sentence, although she doesn’t agree with the way it slams the door shut on parole.

“To me, the bottom line is he took another life,” she says. “I don’t know if I’d have taken away possibility of parole, but I would have imposed a very stiff sentence. The victim had rights too, and so did his family.”

The decision to deny Jones’ appeal was “essentially a foregone conclusion,” says Kathleen Byrne, special assistant attorney general representing the state in the Jones case. Appellate decisions repeatedly have affirmed the felony murder statute’s wide-ranging scope.

Once prosecutors file a felony murder charge, the jury must determine only the facts regarding the underlying felony – robbery, in Jones’ case – and whether a death was caused in the process.

“And that’s the end of the inquiry,” says Byrne. “Whether that’s right or wrong is a legislative decision.”

Like many inmates facing hard time, Jones experienced a jailhouse religious conversion. But unlike most, he has taken his recently minted faith and forged ahead into academia.

He studies Scripture in Greek and Aramaic. He pursues college-level courses in theology and philosophy and hopes to attain a general-studies degree. He wants to develop his faith further with correspondence classes through a Florida seminary. He regularly helps with worship services in the Limon prison.

He has one federal appeal left until his options dissolve into a request for gubernatorial clemency or some legislative sea change in the justice system that might affect him retroactively.

“I believe an injustice occurred,” he says, citing both the accidental nature of the shooting and his juvenile status. “I was the pre-eminent ‘dumb kid.’ It doesn’t make sense that the gravity of the crime changes your level of culpability.”

When mandatory life without parole became law in 1990 for first-degree murder, felony murder took on more significance and urgency for the legal defense community, which realized the combination of laws created a powerful set of tools for prosecutors. Over the next few years, the law would be assailed by critics as unfairly casting a net over defendants who didn’t have a direct role in a murder.

That conflict culminated in the case against Lisl Auman, an adult, who got life without parole despite the fact that she was sitting handcuffed in a police car when an acquaintance fatally shot a Denver police officer in 1997. The Colorado Supreme Court eventually threw out the verdict over a flawed jury instruction, but the statute remained intact.

Among other criticisms: Prosecutors sometimes use the threat of a felony murder charge as a hammer in plea negotiations – with varying reactions among juvenile defendants.

Joshua Beckius, who was 14 at the time Boulder authorities believed a group of youths robbed a movie theater and killed the manager, initially denied involvement in the 1993 crime when police pointed a finger at him two years later.

But under pressure to plead to second-degree murder or face felony murder charges and potential life without parole, he took the deal – even as serious discrepancies emerged among witness accounts. His hopes of a six- to 10-year sentence reflecting his youth and a lesser role in the incident vanished as the judge gave him 40 years.

He’ll be eligible for parole in 2013.

Lorenzo Montoya, also 14 at the time of his offense, had a different dilemma when he was charged in the New Year’s Day 2000 murder of a Denver teacher.

Denver prosecutors believed that as many as five people participated in the killing, and they singled out Montoya for a deal. If he would identify and help convict the others involved, authorities would let him plead to lesser charges carrying only a six-year sentence in the Youthful Offender System, which offers education and rehabilitation.

Against the urgings of his family and his lawyers, Montoya rejected the deal, insisting on his innocence. A jury found him guilty of felony murder, and at 15 he went away for life without parole.

Retired El Paso County District Judge Jane Looney believes the state should examine whether felony murder unfairly targets youths and whether indeed it can be considered an effective deterrent.

“I’ve given lots of thought to this, and I think it’s not a deterrent,” she says. “I just don’t see it that way. When kids are acting out, they’re not thinking about the law.”

Claim: Denver DA’s Resentencing of Some Juvenile Lifers Is Illegal

Arguably the least controversial of these cases involved Trevor Jones, who was highlighted in a 2007 PBS piece about Colorado’s felony murder statute. The report notes that on November 21, 1996, Jones, then seventeen, and his sixteen-year-old friend, Matt Foley, engaged in a bogus gun-sale scheme that ended with Foley being fatally shot in the head. Jones maintained that the shooting was accidental, but a jury convicted him of reckless manslaughter as well as robbery — a combination that was transformed into felony murder under the state’s laws at that time.

Last August, McCann spokesman Lane confirms, Jones was resentenced to 42.5 years in prison and ten years of mandatory parole for felony murder only, without any mention of the robbery charge.