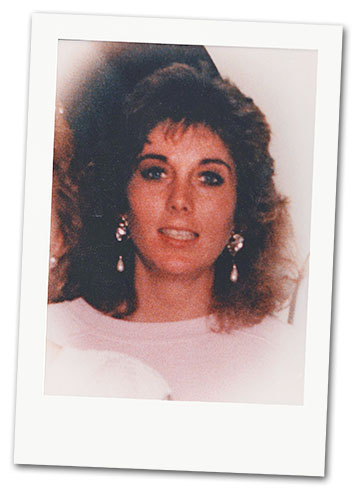

Victim: Cathy Lyn O’Daniel, 26, & her unborn baby

Murderers: Gary Brown, 15, & Marion “Marvin” Berry, 15

Crime date: November 18, 1986

Crime location: Alvin, TX

Crimes: Kidnapping, gang-rape, murder, killing to eliminate a witness, & arson

Weapon: .22 Colt pistol

Murder method: Four gunshots

Murder motivation: Witness elimination

Sentence: Berry — 55 years; Brown — 54 years.

Summary

Berry and Brown kidnapped and raped Cathy and then shot her four times to eliminate her as a witness. The assailants then tried to burn her body to destroy evidence. Brown was released from prison in 2010 after serving 23 years of a 54 year sentence.

Details

According to Brown’s confession during a victim-offender mediation described in the article below.

Cathy encountered Berry and Brown at a gas station, and, seeing that they were having trouble with their car, offered to give them a ride. Cathy took them to Alvin but when they got there, things took a turn for the worse. The offenders told her to go down a dirt road. When she asked why, Berry pulled a gun on her, pointed it at her head, and said, “Don’t worry about it; just do what we’re telling you.”

Berry and Brown gang-raped Cathy (this part was not in the confession in the Face To Face article). They initially planned to leave her in the field with only panties and a shirt. They considered tying her up and then decided to disable her. The plan now was to shoot her in the leg to slow her down and give them time to get away. The then plan changed yet again. Now, Berry and Brown wanted to kill the victim, as she had seen their faces. Cathy begged for her life, telling them they could take her car and money and she wouldn’t say anything. As Berry pointed a gun towards her, she said ‘I forgive you, and God will too.’ She then put her head down and was killed by four gunshots.

Parents of Murdered Children national executive director Nancy Ruhe-Munch questioned the authenticity of Brown’s account, arguing that he may be trying to benefit himself. “Who’s telling [Linda] this? One of the young men? Very believable, huh?…It sounds like if she could forgive them, then maybe I should forgive them. We’ve heard this before. Let me ask you a question: Is this young man coming up for parole?”

Face To Face

Five miles south of Wichita Falls and ten miles east of nowhere sits a depressing series of warehouse-type structures plopped in the midst of unremarkable pastureland. The Allred Unit prison is ringed by three chain-link security fences, 12 feet high and 50 feet apart, each dripping with row upon row of coiled razor wire. Sunlight shatters off the barbed metal, assaulting eyes for miles across the North Texas prairie.

That same stark scene extends to the Allred chapel. Except for the portable pulpit and a bookcase full of old hymnals, there’s little to distinguish it from the other concrete and metal box-structures that constitute one of the world’s largest prisons.

On a Saturday last spring, Linda White and her granddaughter Amy perched uneasily on cheap metal chairs around a battered foldout table set up especially for them in the middle of the chapel. A solitary gray-uniformed guard kept watch from behind a glass partition.

The two visitors waited for the delayed arrival of the man who would take the chair an arm’s length across from them, even though he was already nearby. Inmate Gary Brown, despite nine months of preparation for this meeting, was practically hyperventilating in an adjoining room. Repeated efforts to regain his composure failed. Finally, he staggered into the chapel, red-faced and trembling. Brown held his head in his hands, body withdrawn, feet pointed inward as if willing himself to shrink.

To the Whites, he was both a stranger and a force that had forever altered their lives 14 years earlier. Brown, after a life of running away, may never have felt more like running than he did at that moment. He wanted to explain. But he couldn’t bring himself to look at the two women. Or to stop crying.

“I can tell it’s going to be a kind of tough day,” said Linda White.

On November 16, 1986, Gary Brown was on the run. A Texas Youth Council official had ordered the 15-year-old into Houston’s Casa Phoenix drug treatment center that summer. And Brown was ordering himself out. “I got hot feet,” he recalls. Brown took off with another 15-year-old center resident, Marion “Marvin” Berry. Their plan was to get high, and soon.

The youths left Casa Phoenix on an employee’s motorcycle, then traded the stolen bike for a chunk of cocaine and a pair of syringes. They spent that Sunday night shooting up under a bridge in northwest Harris County, near the area where Berry had grown up.

The following evening, Brown and Berry stole a station wagon from a Target parking lot. Its owner had been loading furniture and had left the engine running. The stolen wagon came with a bonus: A loaded .22 Colt pistol was stashed under the seat.

The furniture was quickly sold for more dope. Brown and Berry began injecting speedballs, a potent cocaine-methamphetamine mix that produces a euphoric sense of wellness. They felt invincible. Barely 24 hours into their adventure, they’d acquired drugs, a gun and a car. They were real gangsters now.

Brown’s escape — if walking off from a treatment center can be called an escape — was the latest episode in a dysfunctional existence. He never knew his father; his alcoholic mother left him in an orphanage for a few years.

By the time he was in second grade, a teacher noted that he lied, stole and set fires. At the age of eight, he fled home for the first of many times. He says he was trying to get away from his stepfather, who had some twisted ideas on discipline. According to the youth, “Either I could return a favor in a sexual way or I could get my butt whipped.”

Brown made it to third grade before attempting suicide — by swallowing a bottle of Tylenol. “I thought it would kill me,” he says. This led to the first of four trips to Terrell State Hospital.

When he became a teenager, Brown was already abusing alcohol and a smorgasbord of narcotics. Bounced from institution to foster home to jail, he had an extensive juvenile record, mostly for stealing.

In 1984 a juvenile court judge packed Brown off to the Texas Youth Council. The 13-year-old returned a few months later to discover that his mother and stepfather had moved and left no forwarding address.

No one in his hometown of Greenville, 50 miles east of Dallas, was shocked when he was shipped back to youth correctional centers in ’85 and ’86 — or that he fled both times. If there was a dominant motif in the life of Gary Brown, it was that he ran away.

The latest escape showed that Brown and Berry knew more about stealing cars than driving them. They filled the station wagon tank with leaded gas; the engine ran on unleaded fuel. The teenagers pulled the vehicle into an Exxon station near FM 1960 and Champion Forest Drive.

In a comic attempt to mix the blends of gas, Brown was bouncing on the rear bumper of the wagon, when, almost as if on cue, a tan sedan pulled up.

It was nearly midnight when the driver — a slender, attractive, blue-eyed brunette — asked about their car trouble. Brown explained about the problem with the gas in his “dad’s” car. Aw shucks, Brown told her, he’d never hear the end of it if Dad found out. He mentioned friends in Alvin with tools that could help him.

The woman asked if they needed a lift. She said her name was Cathy.

Cathy Lyn O’Daniel was raised in a handsome two-story country home set at the back of five lush acres in the Decker Prairie area between Magnolia and Tomball. Her parents, oilman John White and homemaker Linda, had raised her and brothers, Steve and Johnny, in an atmosphere of affection and security. Cathy had wanted for nothing.

In 1978 she graduated from New Life Academy, a private Christian high school in Tomball. She married Phil O’Daniel and gave birth to daughter Amy in 1981. They split up a year later. The vivacious, bubbly woman had some rough moments raising Amy alone — without child support — but she had her family to fall back on in hard times.

As different as her upbringing was from that of the young stranger named Gary Brown, they shared one trait: serious substance abuse problems. But where Gary ran from his demons, Cathy stared hers down. She had been sober for over four years.

Her mom remembers Cathy confiding just a few months earlier that she had “finally decided it was time to grow up.” She had just become engaged to a young Houston doctor, and her future was looking good.

Cathy was active in Tomball-area Alcoholics Anonymous groups, and she credited that circle of friends with helping her overcome her addiction.

In keeping with the AA cornerstone of being of service to others, Cathy often let people in the program crash on her couch — people she didn’t even know — until they could get back on their feet. Cathy was the kind of woman who brought home strays and fed them. She was easy to talk to and had a knack for making others feel better about their own problems.

Linda White says her daughter did a lot of things that some people would say were foolhardy, “but that’s because she was very compassionate.”

And Cathy knew about car trouble. She drove a fixer-upper — a ’76 Pontiac Grand Prix — that her brother and roommate, Steve, kept running for her. So it seemed natural to offer a lift to two stranded teenagers, even ones needing a ride all the way to Alvin.

And no one appeared to know what was about to happen as they headed onto FM 1960 that crisp, clear Monday night. But Gary Brown and Marvin Berry were beginning to think the same thing about their pretty 26-year-old driver.

On Tuesday morning, Cathy’s five-year-old daughter, Amy, went into her mom’s room to wake her for breakfast. She found an empty bed. Amy went downstairs to look for Cathy. Steve already had left for work, unaware that his sister was gone. The house was eerily silent. The frightened child phoned her grandmother.

Linda White called Cathy’s fiancé, Willis Parmley, but he hadn’t seen her since Sunday. Cathy wasn’t at work, and none of her friends knew where she might be. That evening, the mystery widened when the telephone rang at the home shared by Steve, Cathy and Amy.

A caller asked Steve for Willis, who didn’t live there. When Steve identified himself as Cathy’s brother, the male voice said only that he was a friend. “Cathy asked me to call and tell you that she needs to get away for a while and think about some things,” Steve was told. The caller sounded sincere to Cathy’s brother.

“She said for y’all not to worry.”

With that said, Gary Brown hung up.

The next day, another phone rang — at the police station in Greenville.

An apartment resident reported that two suspicious characters had been seen in the complex’s parking lot, checking car doors. They acted like thieves. Officers investigated and found two passed-out youths in a parked tan Grand Prix.

Officers recognized Brown and knew he was supposed to be locked up somewhere. The car hadn’t been reported stolen, but the boys’ nervous explanation — that a friend had lent them the car — sounded unlikely. The cops sensed trouble. Who would lend a car to Brown? They took him and Berry into custody and held them on escape charges from the youth facility. A search of the car revealed a driver’s license with the smiling face of Cathy Lyn O’Daniel.

Armed with an official complaint from the Whites, the Harris County sheriff’s office dispatched two officers to Greenville. They separated and grilled the two youths. Berry caved on the following morning, admitting the car was stolen. He said Brown had run over its owner, killing her.

The cops confronted Brown. He denied killing anyone. If he led them to the body, Brown wanted to know, would police be able to tell what really happened?

Early that Saturday, Brown rode with Harris County deputies back toward Houston. Four miles south of Alvin, on Texas 35, he directed them onto a dirt road leading to an old rice field. Under a pile of brush lay Cathy’s decaying body. She had been raped and shot four times. Brown and Berry, in a clumsy attempt to conceal her identity, also had tried to burn the body by setting fire to Cathy’s long brown hair.

For the last five days, Linda White had hoped that the mysterious phone call to Steve had been legitimate. Perhaps, the White family thought, pressure of a pending marriage or other stress meant Cathy really did need to get away. Even thoughts that she’d started drinking again were better than the unthinkable alternative.

“That week,” Linda says, “I tried not to spend one moment alone.” When she arrived home with Amy late Saturday afternoon, Linda definitely wasn’t isolated. Vehicles packed her driveway. She knew immediately why they were there. But Amy didn’t. Then a five-year-old, she recalls thinking that a house full of people meant that there must be a party going on. She bolted from the car and ran inside, laughing and ready to play.

Linda let Amy go ahead of her, knowing that her husband soon would be out searching. When he found Linda, John White said, “It’s the worst thing possible.”

Then it was Amy’s turn. “I remember going into my grandparents’ room and everyone — Steve, Johnny and my grandparents — were sitting on the bed crying. They all looked at each other not knowing who was going to say what.” Amy doesn’t remember John’s exact words to her, but she says, “I remember it hit me really, really hard for being five years old. I really did know that she was dead — that she wasn’t coming back…and I remember that all I could say was ‘But Mommy’s pegnant, Mommy’s pegnant.’ “

The girl who couldn’t yet pronounce her r’s had been more excited than anyone that her mother was two months’ pregnant.

Cathy O’Daniel’s funeral was described as among the biggest ever held in Tomball.

The case against Gary Brown and Marion Berry was what prosecutors call a slam-dunk. There were signed confessions, a gun, a beautiful victim and savage cruelty.

A county court jury found Berry incompetent, but doctors from a state mental hospital declared him fit. The two youths were certified as adults and likely would have faced the death penalty if not for a Texas law that bars executions for those under 17 at the time of the offense. As jury selection was under way in Brazoria County in October 1987, Berry struck a deal to avoid a possible life prison term. He got 55 years. Brown held out until January 1988 and got 54 years. At an age when they couldn’t even get into an R-rated movie, the pair were entering state prison.

And Linda White candidly thought she might be going insane. Not long after the rape and murder of her daughter, her closest link to Cathy suddenly was gone.

Amy’s paternal grandparents had picked her up the day after Christmas in 1986, promising to return her two days later. They didn’t. Cathy’s ex-husband, Phil, called on December 28 to tell them he’d determined that Amy belonged with him.

The Whites begged Phil to return the girl. They protested that the last thing the child needed at that point was to be uprooted from familiar faces and surroundings — and that Phil had not been around for emotional or financial support in years.

The Whites didn’t see Amy for six weeks, not until a detective they’d hired found the little girl in Arkansas with Phil and his parents. Police brought her back home, and a bitter custody battle ensued. In 1987 both branches of the justice system entangled the Whites: in civil proceedings for Amy’s custody and in criminal court with Cathy’s ghost.

“Sudden death,” says Linda White, “is a great teacher.”

She was a product of the Bible Belt who had always done what women of her generation were raised to do. White married young, had kids and busied herself with being a mother and wife. She’d taken a few college courses, but essentially White sort of drifted. In one of her last conversations with Cathy, her daughter had laughed and said, “Mom still doesn’t know what she wants to be when she grows up.”

White had always been interested in psychology but had never seriously considered pursuing that field. Cathy’s murder would change everything.

After the shock and pain and rage, White began reading books on loss and grief. She found comfort in knowledge, and soon decided to go back to college and become a grief counselor.

White recalled an incident with a friend, a pharmacy worker whose son had died a few months earlier in a tractor accident. As White approached the pharmacy counter, she thought to herself, “I’ll be doing her a favor by not mentioning her son.” “After Cathy died,” she says, “I saw how ignorant that was; like I was going to remind her of that — like she’d ever forgotten for a minute that her child was dead.”

“I thought about that a lot after Cathy died,” says White. “Maybe you don’t have to have your child die to learn the right things to say to someone.” White enrolled in psychology courses at Sam Houston State University in the fall of 1987. She earned her bachelor’s degree in 1992 and her master’s in 1996. She began teaching at Sam Houston, and in 1997 she was offered another teaching job — in prison.

“My department head taught in the prisons, and he always said good things about it, so that planted a seed.” White began teaching college psychology and philosophy in Huntsville-area prisons. Gary Brown or Marion Berry might have turned up in one of her classes. She never would have known it.

“Around that time, someone asked me about the case, and I couldn’t remember their names.” Today Linda White carries a worn newspaper clipping in her wallet that details their sentencing.

White’s attempt to bring meaning to the unfathomable brought her into victim support groups like Parents of Murdered Children, the largest such group in the nation.

In 1987 some of its members had her appear in a video that advocated death-penalty eligibility at 13, the biblical age at which a boy becomes a man. “What I said was ‘If you’re old enough to do these things, you’re old enough to pay the penalty,’ ” White says. “I didn’t know what I was talking about then.”

The more White learned about the human condition, and the more she studied criminal justice issues, the less certain she became about many things. Much of what she heard at meetings of Parents of Murdered Children ran counter to what she was learning in college. She needed the support, and was glad the group existed, but aspects of it bothered her. “I was signing these ‘parole block’ petitions — everyone did it — without knowing much about the case, and I began to wonder if maybe some of these guys might deserve parole. There was really no way to tell from the petition.”

Her inmate-students provided some healing. “Teaching in prison, I began to see offenders more as human beings. One day, one of my students told me that he wished that he could talk to his victims the way he talked to me.” She thought of Brown and Berry. The Whites still had a lot of questions about that night.

There had been no trial, and accounts in The Houston Post and Houston Chronicle had been sketchy and inaccurate. Some of the articles hadn’t even spelled Cathy’s name right. “We always told people, ‘We don’t know exactly what happened,’ ” White says. “But I had always wondered exactly how she ended up with them, and I really needed to know what her final hours were like.”

White was influenced by Changing Lenses, a book by Dr. Howard Zehr that has become the bible of a movement known as restorative justice. Zehr argues that the U.S. legal model, called retributive justice, is not working. A century or more of retribution, says Zehr, has led the United States to become a nation of jailers with the highest crime and incarceration rates of any major country.

Restorative justice proposes that the needs of the victim, offender and community must be reconciled for real justice to occur.

Zehr, who was appointed to assist victims of the Oklahoma City bombing, believes that retributive justice, with its emphasis on impersonal code and passive punishment, ignores the victim, hardens the offender and costs the community in many ways.

“There is both a public and private dimension to crime,” says Zehr. “My argument…is that we’ve taken the public dimension and obliterated that private dimension.”

Retributive justice considers crime an offense against the state. “A victim feels ‘The hell you say, this is against us,’ ” White says. “All [the state is] about is deciding what should be done about all this.”

In the restorative model, the state acts as more of a facilitator. The court enters the process if the victims and offenders cannot work out their own agreement for recompense.

Zehr says that both models derive from the same morality. “When a crime occurs, the victims are owed and the offenders owe,” Zehr explains. “What we’re differing on is what currency will fulfill that obligation. Retributive theory says punishment will do it. Restorative justice says it takes an active effort by the offender to make things right.”

This often leads to a mediation or dialogue between victim and offender.

Victim-offender mediations stem from an idea in the late ’70s by two Canadian probation officers in Ontario. Two young vandals, in the few months after meeting with the owners of cars that had been damaged, paid the victims in full, which rarely happens with court-ordered restitution.

But Linda White didn’t have a broken headlight; she had a dead daughter. There was no paying that back, and critics argue that restorative justice cannot properly address crimes of intended, severe violence. But White found out that one state had a program that put victims of violent crimes together with their offenders. And it was right here in Texas.

The Victim Offender Mediation/Dialogue Program of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice had been offering mediation services to victims since 1994. Three women willed it into existence: Cathy Phillips, Raven Kazen and Ellen Halbert.

In 1990 Phillips’s daughter had been working at an Abilene convenience store less than a week when Anthony Yanez abducted her. Brenda Phillips was raped, strangled and dumped alongside a road. While post-trial proceedings may now include formal statements from victims, officials shook their heads then when Phillips asked for a meeting with the killer in 1990.

Still obsessed by thoughts of the ordeal suffered by her daughter, Phillips watched an HBO special on victim-offender mediations. Soon she was in contact with Kazen, director of the then-three-year-old Victim Services office of TDCJ.

Phillips told her, “Raven, I want to meet Anthony Yanez face-to-face. I need to know how long it took Brenda to die.” Kazen says the call “took my breath away.” But the system had no program for taking victims into prisons, and she knew prison officials would resist.

Kazen turned to Halbert, a member of the Texas Board of Criminal Justice who had connections to then-governor Ann Richards. The Austin woman was also in the victims’ rights movement after being attacked by a rapist dressed like a ninja who hammered a knife into her skull in 1986.

Cathy Phillips, with the help of the two women, finally met Yanez in the Ellis Unit outside Huntsville in 1992. An HBO film crew went along. Kazen brought in a mediator from out-of-state. “We just put them together…no preparation,” Kazen says. In the 90-minute session, Yanez detailed the killing and apologized. Phillips told him what a chickenshit she thought he was.

She left without forgiving. But she says she felt better — a lot better.

Excited by the positive experience of Cathy Phillips, Kazen launched TDCJ’s mediation program. It began primarily in the personage of David Doerfler, a psychologist and ordained Lutheran minister with twinkling eyes and a soothing voice. He is also a crime victim. A drunk driver killed Doerfler’s brother-in-law, and his daughter has permanent injuries from an accident involving another drunk motorist.

Doerfler, who had worked in a program that brought sex offenders into contact with victims of sexual abuse, felt TDCJ’s mediation program needed more structure to ensure the dialogues would be both safe and healthy.

Kazen insisted that the entire process would need to be initiated by the victim, and the offender had to be willing to admit guilt. “We’re not going to take requests from offenders, and we’re not going to retry the case,” says Kazen.

Training was considered absolutely essential. Victim, offender and mediator all go through about 100 hours of preparation — it can take a year — before the actual meeting.

While only nonviolent crimes were being mediated by other states’ programs, Doerfler and Kazen decided that any victim should have access in Texas. “We were hoping we’d get some experience with nonviolent cases,” says Kazen, “but guess what? No nonviolent victims called us. It was rape victims, and mothers and fathers whose children had been murdered…”

In 1999 one of those mothers was Linda White.

White, then pursuing her doctorate in adult education, volunteered to be a mediator for Doerfler in 1997. He convinced her that before she handled anyone else’s mediation, White first needed to do her own.

It had taken Linda White 13 years, two degrees, teaching in prison and a little coaxing to get to the point where she felt like she could meet the men who had raped and murdered her daughter. Amy White had always been ready.

Linda “was always like, ‘I don’t want to talk about it’ — nobody did — but I was always curious,” Amy says. “They were 15 years old, and that really hit me, especially when I got to that age.”

Now a 19-year-old college freshman, she is tall and slender, with the same quick smile, attractive figure and long brown hair as the woman she calls Cathy. John and Linda White legally adopted Amy after Cathy’s death, and she calls them Dad and Mom.

When she became pregnant in 1999 with her son Chase, Amy especially wanted to learn all she could about Cathy. “People would always candy-coat her for me. But I wanted to know everything, not just the good stuff. I wanted to know her as a person.”

Willingness by the Whites wasn’t enough to ensure a meeting with the killers. Once victims request mediation, offenders are contacted to see if they are eligible and willing to participate. Ellen Halbert, as the volunteer mediator, made her search into the prison system and psyches of the killers.

TDCJ officials quickly nixed the participation of Marion Berry, deeming the psychiatric patient unsuited for the emotionally intensive process. That left Gary Brown.

Brown entered the system in 1988, when Texas prison gangs were at their zenith, and on some units they ran the cell blocks. Teenagers were bartered for cigarettes and sodas. Brown nearly fell into the trade.

In ’89 he was placed in protective custody after almost being stabbed with a shank in a prison drug deal gone awry. In ’90 Brown began to plot an escape. His plan was farfetched, but Brown recalls that he’d already attempted suicide, so being shot going over the wall didn’t sound half as bad as life in prison.

Brown was ready to run again when he got a new cellmate, Cory Corley. Corley claimed to be innocent and told Brown that he’d asked God to place him in a cell with someone who needed his help. “Whatever,” thought Brown.

But Corley turned out to be sincere. He felt for the sad-eyed kid who was alone. Brown, who had never had a visitor in prison, was soon visited by Corley’s parents. When Corley’s conviction was overturned in ’92, Brown was adopted by the Corleys. For the first time in his life, he had a real family. That support matured and changed Brown. In the summer of 2000, he was ready when asked about beginning the mediation process. “He was so grateful for the chance to tell them how sorry he was,” mediator Halbert says. “He cried and said he felt like he was blessed by God.”

All the participants moved on into the mandatory paperwork and writing involved in the program. Brown began talking about his crime. He said, “We took advantage of her and gave her no choice on it — sexually.” Halbert, survivor of the ninja rapist, softly insisted, “Gary, you need to say what you did to her.” Slowly, the details began to emerge.

On April 21 Gary Brown entered the prison chapel of the Allred Unit and took his seat across from the mother and daughter of the woman he murdered.

Linda and Amy White, who had never seen Brown in person or in photos, were shocked at how young he seemed. “I thought he was going to be an old man,” Amy says. “He looked like a little boy.”

And they never expected that Brown would already be crying as he came in.

“The main thing I want you to get out of this, Gary,” Linda told him, “is I want you to know a lot about us and what the last 14 and a half years have been like for us — not just the bad, the good things too…and I want to know the same things about you.”

Then Linda went to the heart of the matter. “One of the problems we have, Gary, is that we never did have enough of what really happened to put things together…I feel like the sooner we can — maybe we just need to get past that — can you do it? We’ll let you know if we get to a point where we can’t listen.”

The confession came tumbling out of Brown. “She saw we was having trouble with the station wagon — everything I’m telling you is true — I’m not making nothin’ up. I’m not trying to make myself look good or my ‘fall partner’ [Berry] look good or anything. It’s just the way it went. She saw us having trouble, and out of curiosity, she asked what was wrong.”

Amy asked, “Do you know why she was at the gas station?”

Newspaper reports had stated that Cathy had stopped to put water in her radiator. Her brother Steve, who had worked on her car, had felt guilty — that if only he’d fixed her car better, his sister might still be alive.

“She was getting gas, I remember that,” Brown said, unaware of the importance of his answer.

“She was just getting gas?” asked Linda.

“Yes, ma’am. At that time she said, ‘I can take y’all to Alvin if you want and’ — honest to God’s truth, this part was voluntary; at that time the gun was never pulled. She didn’t even know we had it. It’s when we got close to Alvin — that’s where things wind up changing.

“I led her down, told her to go down a road that I knew was going to nothing — out in a pasture. And then when she asked why — Marvin pulled the gun — he had the gun on her and said, ‘Don’t worry about it; just do what we’re telling you.’ “

Then Linda asked what every victim wants to know, and for which there is never a good answer. “Do you know why it went in the direction it went?”

Brown says that they planned to leave Cathy in the field wearing only panties and a shirt. They talked of tying her up, then decided to disable her.

“The thought was, shooting her in the leg would give us time to get away. Honest, at first there was no intent — it did change up — but there was no intent of killing. It was to slow her down so we could get in the car and get away, and be long gone before she could tell anybody what happened.”

When the first blast cracked into the black sky, Brown and Berry suddenly felt they’d passed the point of no return, that they could be caught if they didn’t execute her.

“In our minds we felt like we had no choice about this. She’s already seen our faces.”

The Whites, at this point near tears, began sobbing as if comprehending the pointlessness of Cathy’s death for the first time.

“It wasn’t like she pissed you off or she was…like you didn’t even have to force her” to give you a ride, Amy said. “She was just doing it to be nice…Was pretty much the last thing she said was just ‘Why?’ “

Brown could barely tell about Cathy’s final seconds.

“When she was out there…and she heard me and him talking and we had realized we had already gone too far…she said, ‘You can take the car, you can take the money, you can take anything you want and I won’t say nothing.’

“And then, as Marvin pointed the gun towards her way, she said, ‘I forgive you, and God will too.’ “

At the word “too,” Brown dissolved into tears.

“And then she put her head down.”

Everyone in the room was weeping when he spoke again.

“And if I don’t remember anything else that night as clear as I did, it was that right there.”

Except for the quiet sobbing, not a sound was heard in the chapel for a minute and a half. Linda White held Amy. A strange sensation of grace and forgiveness — of a woman dying in an isolated field — permeated the room.

“That,” Linda whispered to Amy, “was your mama.”

For six hours inside this small prison chapel, with a break for lunch, the family and Brown explored their lives. Linda showed Brown a photo album that detailed Cathy’s life. They talked about Amy’s son.

Brown told them about his life in prison. They discovered that all three of them loved the TV series Touched by an Angel.

When the session ended, the three of them posed for a picture. And Linda, who has probably given a million hugs, gave one to Brown. So did Amy.

“It was hard for me to hug him,” says Amy, “but I felt like it was necessary.” Linda says, “It was the most logical thing in the world for me to hug Gary.”

Some members of the White family see the embrace as illogical. Steve White’s wife, Peggy, says she “went ballistic” watching the video of Linda’s hug. “Cathy’s murder,” Peggy says of her husband, “has messed him up bad.” She says the image of the hug caused “the biggest fight we’ve ever had.”

Linda and Peggy White no longer speak about the mediation. John White leaves the room whenever the video of the mediation shows Brown’s face.

The family’s division is minor compared to the controversy that the mediation program and other restorative justice issues generate among members of victims’ support groups.

Justice For All, which declined comment, is skeptical of the program. Nancy Ruhe-Munch, 15-year national executive director of Parents of Murdered Children, questions the motives of Brown — or any inmate.

“Who’s telling [Linda] this? One of the young men? Very believable, huh?” The head of POMC doesn’t think much of Brown’s account of Cathy O’Daniel’s final words. “…It sounds like if she could forgive them, then maybe I should forgive them. We’ve heard this before. Let me ask you a question: Is this young man coming up for parole?”

Indeed, Brown becomes eligible for parole in 2004. But one of the core principles of the program is that offenders will not benefit in any way — except internally — from the mediation process. Parole board documents will contain no mention of Brown’s mediation.

Those who’ve seen the video of the mediation almost invariably come away convinced of his truthfulness. His account matches with known facts of the case; he confesses previously undisclosed details and admits making the cold-blooded call falsely assuring Cathy’s family about her disappearance.

Lisa Jackson, a gang-rape survivor and Emmy-winning filmmaker, videotaped the mediation as part of an hour-long segment that aired September 19 on the Court TV series The System (the segment is scheduled to be rebroadcast November 1 on Court TV). Jackson says that in more than 30 years of doing reality television productions, the mediation “stands out as one of the most authentic moments” she’s filmed or personally witnessed.

But Ruhe-Munch believes that no more than perhaps one or two inmates out of 100 will be honest in such mediations. “The rest of them are just giving [victims] a line of crap.”

Carolyn Hardin, leader of the Houston Heights POMC chapter, makes Ruhe-Munch sound almost passive. Hardin’s son Steven, a wrecker driver, was killed in 1998 by a man who was about to have his truck towed. She’s angry at the probated sentence in the case.

“My husband said he’d mediate — with his .45,” Hardin says. “These mediation people are great. How are these people getting this funding? DO-GOODERS. They think they can reform the world. Well, look. I go back to the Bible: An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”

Hardin says that while the organization doesn’t tell others what they should do, “we actively oppose do-gooders who push stuff down our throats.”

Linda White, who belongs to the group Murdered Victims’ Families for Reconciliation, says critics of mediation don’t seem to realize that the process forces convicts to confront the personal tragedy they caused.

“If you commit an offense…you should not be allowed to go off and serve a passive prison sentence,” she says. “You should have to face the victims.”

Doerfler measures his words like diamonds in commenting on groups that advocate retributive philosophies. “Some of the more extreme groups, they really come across as expressions of the hate and rage and are kind of fearful to let go of that. That’s not necessarily their aim, to lock people in, but oftentimes they do not challenge them to go beyond that.”

Kazen understands. “They feel like that if they let go of the anger, then the other guy wins; like if they stop being mad, they’re letting down their loved one.”

While hard-liners scorn the concept, over 500 victims — some among the ranks of POMC and Justice For All — have inquired about the mediation process or signed up for it. More than 40 mediations have been conducted. Three of those involved death row inmates who were subsequently executed, making Texas the only state to extend the program to convicted capital murderers. Several states now offer mediation for victims of violent crime.

Doerfler, who retired September 1, thinks there is the potential to make a tremendous difference. “It’s not a panacea, but it sure as hell is a main element.” He terms it “the closest thing to pure accountability you’re going to get.”

Amy White talks about finding peace from the session, especially when she learned of her mother’s last words. “Someone in your family getting killed and having the actual complete healing of someone, forgiving and completely letting go — not too many people get that opportunity.”

Linda White, who completed her Ph.D. in August, sees Cathy’s final statement to her killers as a blessing from her daughter for the later work in restorative justice.

“I thought about it constantly over and over all day. And a lot of it was because I could never think about it before — those last few moments. It was such a validation for me and Amy…It’s as if she said, ‘Mom, you’re doing the right thing,’ ” White explains. She knows there are other victims still clinging to a rage they cannot release.

They’ll never get enough vengeance,” White says, “because there isn’t any.”

Brown says he’s humbled by the kindness shown him by the Whites. He is concerned that the publicity over the mediation could make prison life harder for him — inmates with sexually related offenses often face harassment from other convicts and even guards.

He worries. But for Gary Brown, the running in his life is over.

“I’m doing this because I done something wrong,” he says. “I wanted to do everything I could to make things easier for them…any kind of relief that they could have, that’s what I hoped would happen. I done something bad, but there’s something good in me.”