Murder victims: Ralph Geiger, 56, David Pauley, 51, and Timothy Kern, 47

Attempted murder victim: Scott Davis, 49

Age at time of murders: 16

Crime dates: August 2011-November 2011

Crime location: Akron and a southeast OH farm

Partner in crime: Richard Beasley

Murder method: Gunshots to the victims’ heads

Weapon: Victims were injured and killed with .32 and .38 caliber bullets

Motivation: Robbery

Convictions: Aggravated robbery, kidnapping, attempted aggravated murder, and aggravated murder

Sentence: Life without parole (LWOP) later reduced to 25 years to life by SB 256

Incarceration status: Incarcerated at the Trumbull Correctional Institution and eligible for parole in November 2036 due to SB 256

Summary

Rafferty and his co-defendant Richard Beasley murdered three men and attempted to murder another between August and November of 2011. The serial killers lured the men to their deaths with fake job offers. They targeted men who were desperate for work and down on their luck and who had few family ties that might highlight their disappearance.

“We took him out to the woods on a humid summer’s night … The loud crack echoed and I didn’t hear the thud.”

Poem found on Rafferty’s computer describing the murder of Ralph Geiger

Rafferty was sentenced to life in prison without parole. However, SB 256, which went into effect on April 12, 2021, mandates that all juvenile criminals be eligible for parole unless they are the principal offender in at least three murders.

Timeline

2011

August: Ralph Geiger disappears after leaving for a job on a farm in southern Ohio.

October 9: David Pauley responds to an add for a job as a farm caretaker. Scott Davis, a self-employed landscaper in South Carolina who wants to move back to Ohio, also responds to a Craigslist ad for a job on a cattle farm.

October 10: Timothy Kern responds to a Craigslist ad for a farm caretaker.

October 22: David speaks with his sister on the phone for the last time.

November 6: Scott meets Rafferty and Beasley. The serial killers lure Scott to a wooded area and attempt to murder him. Scott survives with a gunshot wound to the elbow.

November 13: The killers shoot Timothy in the head and murder him.

November 15: Investigators find David’s mostly naked body in a grave. It is later determined that he was killed by a single gunshot to the head.

November 25: Ralph’s naked body is found in a shallow grave. Timothy’s body is found in the woods behind a vacant mall in Akron. Ralph was killed by a single gunshot to the head, while Timothy suffered five gunshots to the head.

Details

“Craigslist Murder Case”: Brogan Rafferty, Ohio teen, sentenced to life in prison

(AP) AKRON, Ohio – A teenager was sentenced to life in prison with no chance for parole Friday for his role in a deadly plot to lure men desperate for work with phony Craigslist job offers.

Judge Lynne Callahan sentenced 17-year-old Brogan Rafferty, who had been convicted on Oct. 30 of aggravated murder and attempted murder in the deaths of three men and wounding of a fourth.

The sentencing was delayed from Monday amid talks on a deal for leniency in return for Rafferty’s testimony against the alleged triggerman. Rafferty was looking to avoid a life sentence without hope of parole.

The jury rejected the defense claim that Rafferty feared for himself and his family if he didn’t cooperate with his co-defendant, Richard Beasley of Akron.

The 53-year-old Beasley, described as the teen’s spiritual mentor, has pleaded not guilty and faces a Jan. 7 trial.

Prosecutors say the victims, all down in their luck and with few family ties that might highlight their disappearance, were lured with phony offers of farmhand jobs on Craigslist last year.

One man was killed near Akron and the others were shot at a southeast Ohio farm during bogus job interviews.

Prosecutors say robbery was the motive.

Rafferty, a high school student from Stow, was tried as an adult but didn’t face a possible death penalty because he is a juvenile.

Beasley, an ex-convict and self-styled street minister from Akron, could face the death penalty if convicted.

The surviving victim, 49-year-old Scott Davis of South Carolina, testified as the prosecution’s star witness. He identified Rafferty as Beasley’s accomplice and told the jury a harrowing story.

Davis, who was looking to move close to his family in the Canton area, said he was walking across what turned out to be a bogus job site when he heard a gun cock and turned and found himself face to face with a handgun. He said he pushed the weapon aside, was shot in the arm and fled through the woods.

During Rafferty’s trial, defense attorney John Alexander painted Beasley as the mastermind and said that the first killing came without warning for Rafferty.

The three murdered men were Ralph Geiger, 56, of Akron; David Pauley, 51, of Norfolk, Va.; and Timothy Kern, 47, of Massillon. Authorities say they were targeted because they were older, single, out-of-work men with backgrounds that made it unlikely their disappearances would be noticed right away.

Craigslist Used in Deadly Ploy to Lure Victims in Ohio

By Erica Goode

- Dec. 2, 2011

AKRON, Ohio — They were men thrown hard against the rocks of bad fortune — out of work, their marriages broken, their youth, with its possibilities, behind them.

To their eyes, the advertisement on Craigslist, offering $300 a week, a free trailer and unlimited fishing to “watch over a 688 acre patch of hilly farmland and feed a few cows,” may have seemed like a sign that their luck was finally turning.

Instead, in a scheme so macabre that residents here are already speculating on when it will be turned into a movie script, three of the four men, one from Virginia, one from the Akron area and one still unidentified, were lured to their deaths, their bodies buried in shallow graves. The fourth man, from South Carolina, who was hired and driven to the property in rural southern Ohio, was shot in the arm but escaped and alerted the authorities. The “farm” was in fact land owned by a coal company.

More bodies may still be found, as the bogus advertisement, which was picked up by online job aggregators, drew more than 100 responses from Ohio and other states.

In Ohio, hit hard by the recession, the abundance of eager applicants pulled in by the advertisement has surprised no one, stirring talk about the lengths that people will go these days to find employment. “People here are desperate for work,” said a clerk at a motel in Akron, whose employer did not want him to give his name.

The police have suggested robbery as a motive, but other theories have also circulated, including identity theft and, perhaps more chilling, simply a desire to kill. The perpetrators appeared to be looking for loners who would not be missed.

Law enforcement officials have arrested two suspects, Richard J. Beasley, 52, of Akron and Brogan Rafferty, 16, a high school student from nearby Stow. Mr. Beasley, who has a long criminal record, has not been charged in connection with the killings yet but is being held on other charges, including 15 counts of promoting prostitution and also selling the painkiller OxyContin. On Thursday, sources said that the federal government had filed kidnapping and wire fraud charges in connection with the Craigslist case. (The F.B.I. would confirm only that it had issued a hold to keep Mr. Beasley incarcerated.)

Mr. Beasley appeared in court on the drug charge on Thursday, and on Friday he is to be arraigned on the prostitution charges.

Mr. Rafferty has been charged with the attempted murder of Scott Davis, 48, of South Carolina, the aggravated murder of David Pauley, 51, of Norfolk, Va., and two counts of complicity in those crimes. Prosecutors want the teenager, a tall youth who towered over the police officers escorting him from the courthouse in Caldwell this week, to be tried as an adult, something that is virtually routine in Ohio for crimes this serious. Judge John W. Nau of Noble County Common Pleas Court has issued a gag order in the case; he will take up the issue on Dec. 15.

Neither suspect has been charged in the murders of the other victims, Timothy Kern, 47, of Massillon, Ohio, whose body was found last week buried near a mall in Akron, and the unidentified man, whose body was found on the rural property in Noble County, where officials also found Mr. Pauley’s body on Nov. 14.

In a phone interview, Carol Beasley, Mr. Beasley’s mother, insisted that her son was innocent, and said that he had spent hundreds of hours in charitable work, like taking food to the poor, and had taken Mr. Rafferty — “a nice young man” — under his wing. “We never saw anything in Richard that was violent,” said Ms. Beasley, a retired secretary at Buchtel High School in Akron. “I hope the courts will see the truth.”

Yvette Rafferty, Mr. Rafferty’s mother, has said that if he was involved, he must have been in thrall to Mr. Beasley, a family friend. Ms. Rafferty, a striking woman, tall and rail thin, paced in front of the courthouse in Caldwell on Tuesday, waiting for a chance to talk to her son.

“All I know is he would not hurt anyone in the world unless he was threatened,” she said.

One applicant who was rejected, Ron Sanson, 58, a former construction worker, said he was interviewed by Mr. Beasley, who was dining on Chinese food, in the food court of a mall.

Mr. Sanson, who is divorced, said he had been in and out of work since fracturing his leg in 2006. He said potential employers balked at his age, even for jobs shoveling snow. “You’re not going to be out there shoveling snow in the middle of the night,” he was told.

He said he had good antennae for trouble, but picked up nothing strange about Mr. Beasley, who, he said, looked like a farmer, with “a scraggly beard” and a red, white and blue baseball cap.

“He seemed all right with me,” Mr. Sanson said.

He did not get the job; the fact that he had gone to college and been in the Navy may have put Mr. Beasley off, he speculated.

Less fortunate were Mr. Pauley, who had driven from Virginia with all his belongings, and Mr. Kern, who was struggling to support his three children.

Erin Sendejas, who worked with Mr. Kern for five years at a Domino’s Pizza, said that he quit his job as a delivery man several months ago because his car was breaking down and he could not make enough money after paying for repairs.

“He was just trying to find any job,” she s

“He was just trying to find any job,” she said. “When he was here, all he talked about was his kids. He just felt that they were priorities in his life.”

Mr. Kern had been missing since Nov. 13, and his body might never have been found were it not for Mr. Davis, the man from South Carolina who escaped.

Before the gag order was issued, Sheriff Stephen S. Hannum of Noble County had said that his office had responded to a call on Nov. 6 and found “a white middle-aged man” with a gunshot wound to the arm and a story about answering an advertisement on Craigslist.

Mr. Davis told the sheriff that he had met two people for breakfast in Marietta, Ohio, and after leaving his car in Caldwell, was driven to the nearby “farm.”

While walking through the wooded area, Mr. Davis reported, he “heard what he thought was a gun being cocked. He turned to see a gun pointed at his head. He deflected the gun and ran,” hiding in the woods and finally seeking help at a house two miles away.

A search of the property revealed a hand-dug grave, the sheriff said. On Nov. 11, a woman in Boston called the sheriff’s office to say that her twin brother, David Pauley, was missing and that he had answered the same advertisement on Craigslist.

Ms. Beasley said she had met with her son at the Summit County Jail, where he is being held on the prostitution and drug charges. “We prayed for Brogan and this whole situation,” she said.

Jon Platek, the Akron campus pastor at The Chapel, where the Beasleys attended church and often brought Brogan Rafferty, said that Mr. Beasley had attended only very sporadically in recent years. He said that Mr. Beasley used to come with his family, even as a child, and church members remembered him wearing cowboy boots and a big belt buckle, unusual attire in Akron in the 1960s and 1970s.

The crimes have deeply affected the congregation, Pastor Platek said. “It’s one thing to do something out of passion, but it’s another to do something at this level,” he said. “I sit with a lot of deeply troubled people that don’t do this.”

THE STATE OF OHIO, APPELLEE, v. BEASLEY, APPELLANT.

I. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

A. The State’s Case-in-Chief

{¶ 3} The state called 42 witnesses to establish the following facts.

August 2011: Ralph Geiger

{¶ 4} At one time, Ralph Geiger operated a successful construction

business. But by February 2011, he was homeless and living at a shelter in

downtown Akron. He left the shelter in early August 2011, telling the staff and a

friend that he had a job on a farm in southern Ohio. Summer Rowley, a friend of

Geiger’s, testified that Geiger told her that he would not be able to talk to her from the farm because he would not have cellphone coverage. Although they had spoken

daily when Geiger was at the shelter, after he left, she never heard from him again.

{¶ 5} On August 8, Geiger checked into the Best Western Hotel in

Caldwell, a town in eastern Ohio between Cambridge and Marietta. Three adults

were registered in the room for one night. Rowley identified Geiger’s signature

and the phone number on the hotel registration form as his, and she testified that

the driver’s license photocopied by the hotel at check-in belonged to Geiger.

Summer 2011: Richard Beasley

{¶ 6} Beasley stayed for a few nights in the basement of the house of his

friend Joyce Grebelsky on Cramer Avenue in Akron in the spring of 2011.

Grebelsky testified that Beasley later asked her to start calling him “Ralph Geiger”

because he wanted to be a different person and did not want to go back to jail.

{¶ 7} On August 31, 2011, “Geiger” submitted an employment application

to Tech Center, Inc., listing a home address on Cramer Avenue and “Joyce

Grabowski” as an emergency contact. The next day, “Geiger” submitted an

employment application to Waltco Trucking Company, again using the Cramer

Avenue address and identifying “Joyce Grebowski” as a reference. Alex Hartke, a

Waltco employee, testified that he worked alongside “Geiger” in September and

October 2011, and he identified Beasley as the man he knew by the name “Ralph

Geiger.”

{¶ 8} On September 19, 2011, “Geiger” opened a checking account at PNC

Bank, using the Cramer Avenue address. Activity in the account included the

deposit of two checks from Tech Center payable to “Ralph Geiger” and a check

written to Grebelsky dated October 3, 2011.

{¶ 9} The day after he opened the PNC account, “Geiger” sought medical

treatment for chronic pain at Akron Community Health Resources, Inc., where he

was seen by Dr. Michelle Moreno. Dr. Moreno testified that the patient was seeking

prescription painkillers. He told Dr. Moreno that he had had a cervical fusion, the result of an accident involving a dump truck, and had been seeing a doctor in

Tijuana, Mexico, for narcotics. Dr. Moreno had him sign a medical release, treated

his high blood pressure, prescribed a nonnarcotic pain reliever, and told him to

return in seven days. The man returned to see Dr. Moreno on September 27, 2011.

In the interim, Dr. Moreno had tried without success to get records from the Tijuana

clinic.

{¶ 10} Other witnesses testified about meeting a man in 2011 who called

himself “Ralph Geiger.” In July or August, Don Walters Sr. was introduced to a

man who went by the nickname “Dutch.” Once, while shopping together, Walters

saw “Dutch” use identification in the name of “Ralph Geiger.” And in August or

September 2011, Joe Bais rented a room in his house on Shelburn Avenue in Akron

to a man who went by the name “Dutch” but whose driver’s license said “Ralph

Geiger.” At trial, Bais and Walters both identified Beasley as “Ralph Geiger” or

“Dutch.”

October 2011: Daniel DeWalt

{¶ 11} In October 2011, Daniel DeWalt applied by e-mail to be the

caretaker of a cattle farm in Caldwell, Ohio, a job he had found advertised on

Craigslist. After receiving an e-mail response, DeWalt agreed to meet a man named

“Jack” at the Chapel Hill Mall food court in Akron.

{¶ 12} When they met, “Jack” told DeWalt that his uncle, Bob Gaylord,

owned a farm in Caldwell and needed someone to start work right away because a

nearby road was blocked by a landslide. DeWalt filled out an application. A few

days later, “Jack” offered DeWalt the job. DeWalt packed his belongings into a UHaul trailer in preparation for the move.

{¶ 13} But problems arose. DeWalt told “Jack” that he was bringing his

pistol. “Jack” initially said that was okay but then changed his mind, saying, “I’m

the only one with a gun.” DeWalt also told “Jack” that he had been unable to find the alleged property on the county auditor’s website, indicating, “[T]his ain’t

adding up.”

{¶ 14} Additionally, “Jack” wanted to buy DeWalt’s SUV and truck. He

asked to pick up the vehicles on a Friday, promising to pay on the following Sunday

when they got to the farm. DeWalt objected, saying, “[W]hat if somebody is trying

to get my vehicles before I come down there, and then when I get down there, shoot

me and take my stuff.” “Jack” replied, “[Y]ou shouldn’t have said that,” and

indicated that now he needed to consult with his uncle. On October 15, 2011,

DeWalt received an e-mail from “JG” at [email protected] withdrawing

the job offer. At trial, DeWalt identified Beasley as “Jack Gaylord.”

October 2011: George Brown

{¶ 15} George Brown, semiretired from the concrete business, wanted a job

to supplement his income. On October 7, he answered a Craigslist ad for a job

taking care of cattle in southern Ohio. The ad promised a trailer to live in, a credit

card, and $300 to $400 a month.

{¶ 16} Brown arranged to meet “Jack” at the Chapel Hill Mall food court.

The interview was going well until Brown mentioned his lifelong involvement in

martial arts, at which point “Jack” “kind of sat back in his chair.” Brown also

informed “Jack” that for a while, he had worked as a security officer. “Jack” pulled

back Brown’s application and abruptly ended the interview. Brown never heard

from “Jack” about the job. At trial, Brown identified Beasley as “Jack.”

October 2011: Dave LeBlond

{¶ 17} In October 2011, Dave LeBlond was looking for work. He

responded to a listing on Craigslist for a job as a farmhand on a 300-acre farm. A

man who identified himself as “Richard Bogner” interviewed LeBlond at the

Chapel Hill Mall. During the interview, LeBlond told “Bogner” that he had a

fiancée. He was never contacted again about the job. LeBlond identified Beasley

as the man he met at the mall. October 2011: David Pauley

{¶ 18} David Pauley lived in Norfolk, Virginia. He had been unemployed

for about two years when he responded to a Craigslist ad for a farm caretaker on

October 9, 2011. Pauley told his twin sister, Debra Bruce, about a job opportunity

he found through Craigslist on a 688-acre farm taking care of cattle for $300 a

week. He would be provided a trailer to live in and could bring all his belongings

with him. Sometime thereafter, Pauley told Bruce he had been hired and that he

would be leaving Norfolk for Ohio on October 22. Pauley traveled to Ohio in his

blue pickup truck, pulling a U-Haul trailer containing all his possessions.

{¶ 19} Bruce spoke to her brother twice on October 22, once to arrange

payment for his hotel room in West Virginia and again around 8:00 or 9:00 p.m.

She never heard from him again.

October 2011: Richard Beasley

{¶ 20} Prior to October 23, Beasley told Don Walters that he had bid on a

storage unit, like on the TV program “Storage Wars.” At 1:09 p.m. on October 23,

Beasley called Walters. He told Walters that he got the unit, that it came with a

truck and a U-Haul full of things, and that he needed a place to store the items until

he could sell them.

{¶ 21} Shortly after, Beasley arrived at Walters’s home driving a blue

Dodge pickup pulling a U-Haul trailer. At trial, Walters identified a photograph of

the truck. Bruce identified that same photograph as Pauley’s truck.

{¶ 22} Another car pulled in behind Beasley, driven by a young man

Beasley introduced as his nephew. Walters later learned that the young man’s name

was Brogan Rafferty. The three men unloaded the trailer, which was filled

completely with bags and crates, and put the items into Walters’s garage. Among

the items was a laptop computer.

{¶ 23} Beasley came back to Walters’s house the next day, filling his truck

twice with the items, including the laptop, that he wanted to take. He left behind the rest of the items, including an assortment of Christmas decorations that he said

Walters could keep as payment for storing the items.

{¶ 24} Joe Bais, Beasley’s former landlord, testified that in October,

Beasley, whom Bais knew as “Ralph Geiger” or “Dutch,” had a truckload of stuff,

including ammunition cases containing nuts and bolts, Christmas lights, and train

sets, that he offered to Bais in trade for his computer. Bais bought some of the

Christmas lights and ammunition cases.

{¶ 25} On October 24, 2011, Carla Conley, a U-Haul employee in Akron,

saw two men drop off a trailer that was supposed to be returned in Marietta. At

trial, Conley identified Beasley as one of the men.

November 2011: Scott Davis

{¶ 26} Scott Davis was a self-employed landscaper in South Carolina.

Because he wanted to move back to Ohio, he began searching Craigslist for job

opportunities and found a posting for work on a cattle farm. The ad promised a

two-bedroom trailer on a 688-acre farm and $300 a week.

{¶ 27} Davis responded to the ad on October 9, 2011, and received a reply

on October 17, 2011, from [email protected]. The message asked Davis

to send a copy of his driver’s license for a background check and asked whether he

had a truck or tools. The message was signed “Jack.” After further communication

by e-mail, “Jack” told Davis that he had the job. Davis packed some of his

belongings in a trailer and drove to Ohio.

{¶ 28} Davis met “Jack” for breakfast at a Shoney’s restaurant in Marietta

on November 6. “Jack” arrived with a younger man that he introduced as his

nephew. The restaurant’s security camera captured an image of two men, whom

Davis identified at trial as “Jack” and his nephew, waiting for a table.

{¶ 29} After breakfast, the three men put gas into Davis’s truck and then

left together in a white car to drive to the farm. They drove for around 15 minutes

until “Jack” told the nephew, “Drop me off where we got that deer last week.” Davis and “Jack” then got out of the car, and “Jack,” after telling his nephew to

drive up the road and turn around, led Davis into the woods beside a creek. But

after walking farther into the woods, “Jack” said, “Forget this, let’s turn around and

take the roadway.”

{¶ 30} Davis turned around to head back to the road and then heard a click

and a curse word. He spun around to see “Jack” raising a gun. “Jack” fired the gun

and Davis was hit in the elbow. “Jack” continued to fire, and Davis ran. He heard

“Jack” fire the gun four times.

{¶ 31} Davis ran into the woods. Bleeding badly, he hid for seven hours in

the woods, waiting for dark, before returning to the road and walking until he came

to a house. He arrived around 7:00 or 7:30 p.m., pale and shaking, his right elbow

and pant leg bloody. The man inside, Jeffrey Schockling, called 9-1-1.

{¶ 32} While they waited, Davis, nervous, fidgety, and rambling, told

Schockling that he had applied for a fencing job and that he knew they were going

to rob him. Davis said he had all the documentation, all the e-mails, on the

dashboard of his truck. And he said, “I knew I was in trouble when I heard the

click.”

November 2011: Richard Beasley

{¶ 33} In October 2011, Penny Kaufman, seeking a tenant for her Akron

home, answered a Craigslist ad captioned, “Quiet man needs quiet space to live.”

The man who placed the ad said that his name was “Ralph Geiger” but that he went

by “Dutch.” He showed Kaufman a picture identification for “Ralph Geiger.”

{¶ 34} “Dutch” moved into Kaufman’s home on Gridley Avenue on

November 1, 2011. He told Kaufman and another renter, Rick Romine, that he

made extra money buying storage units and selling the contents, comparing his

activity to “Storage Wars.” On one occasion, he described for Romine a particular

storage unit that he was hoping to buy, a unit he said contained a Cadillac, a Harley Davidson, and high-end electronics. He also told Don Walters about that storage

unit.

{¶ 35} Just days after moving in, “Geiger” told Kaufman that he had won a

bid on a storage unit in southern Ohio and was going to pick up the contents on

November 6. He asked to store some of the items, including a flat-screen television

and a Harley, in her basement. But when Kaufman came home from work on

November 6, her roommate, Darlene, announced that “Dutch” “got shot at today.”

“Dutch” would later tell Romine that he was somewhere in southern Ohio and that

he had some stuff that he was going to sell a gentleman, and

somebody’s car broke down, and he was under the hood looking at

the car, and he heard a click, click, click, and he turned around and

hit the gun out of the guy’s hand, and it hit a rock and it went off

and hit the guy that got shot.

{¶ 36} “Dutch” arrived back at Kaufman’s house very late that night and

told her that he had been shot at. He said that when he arrived to get the storage

unit’s contents, two men were already there with a truck and trailer. They offered

him money for the contents and kept raising their offer until he accepted. But they

said he would have to follow them to their house to pick up the money. So the men

loaded their trailer, and he got back in his truck and followed them.

{¶ 37} As they drove down a dirt road, the truck he was following pulled to

the side and the two men got out and lifted the hood. “Dutch” said that he pulled

over and walked around to see whether he could help. As he bent to look under the

hood, he felt a gun to the back of his head and heard “click, click, click.”

{¶ 38} “Dutch” told Kaufman that he struggled with the man and the gun

fired, the bullet ricocheting and hitting one of the men in the arm. According to

“Dutch,” the man who had been shot ran away and the second man said to “Dutch,” “I have something for you.” When that man started for the cab of his truck, “Dutch”

ran to his own truck and drove away.

{¶ 39} Kaufman asked “Dutch” why he had not called the police. He

replied, “[T]here is times you don’t call the police, Penny.” When she continued

to press, he said that the friend who was with him at the time had a warrant out for

his arrest and that he did not want to get the friend in trouble. This is the only

account that “Dutch” gave in which he mentioned a companion.

{¶ 40} Beasley told Walters a similar story: other buyers offered him more

for the unit, he agreed to sell to them and followed them down a country road, they

pulled over, pretending to be broken down, and when he went to help, one of the

men pulled a gun, which misfired. In the version he told Walters, “Dutch” claimed

that he retrieved a Sawzall from his trunk and cut the man’s arm before getting

away.

{¶ 41} “Dutch” also described the incident to Joyce Grebelsky. She

testified that he called her from southern Ohio “in distress, very upset.” He said

that two people had robbed him of $3,000 and put a gun to his head and that he had

heard the gun click. At some point, he told Grebelsky that he had gone down to

southern Ohio to buy pills. And he asked her to drive him back to southern Ohio

to recover his leather coat. They went at night. He directed her down a secluded

dirt road to the spot where his coat was.

{¶ 42} On November 8, “Ralph Geiger” brought a .22 Iver Johnson TP

pistol to Smitty’s Gun Shop for repairs. “Geiger” gave Grebelsky’s address and

the telephone number 245-8961 to the shop. Smitty’s cleaned the gun, and it was

reclaimed on November 11.

November 2011: The Investigation Begins

{¶ 43} Noble County Sheriff Stephen Hannum responded to the 9-1-1 call

about the Davis shooting. At the scene, he spoke with Davis and found him

coherent and forthcoming. Davis said that he had applied for a job with a man he met over the Internet, that the man had taken him to a remote location to look at

what was supposed to be a 688-acre cattle farm, and that Davis had left his own

vehicle in Caldwell because the man said the road was out and he would not be able

to get his truck and trailer down the back road.

{¶ 44} Davis described two men. One was 51 or 52 years old, with dark

and gray hair. The younger was 17 years old and very tall, about six feet five.

Davis said that one of the men looked like he had recently shaved his beard, but

Hannum was unclear which one he meant. And Davis told the sheriff that he had

been shot.

{¶ 45} Sheriff Hannum did not initially believe Davis’s story, in part

because he was unaware of any 688-acre cattle farm in the county. He knew of

only one residence in the area Davis was describing: a farm in Caldwell owned by

Jerry Hood Sr., who was known as “Country.” And Sheriff Hannum thought that

Davis’s description of the two men somewhat matched Country and his son, Jerry

Hood Jr., known as “County.”

{¶ 46} On Don Warner Road, about a half mile from Hood’s property,

Hannum found the rockslide and heavy equipment Davis had described. Country’s

wife, Lois, worked at a local tavern, and Hannum went to see her there. Lois told

him that Country was in an Akron hospital after he had fallen down stairs and

cracked his skull in September 2011. While at the tavern, Hannum spoke by

telephone to County, asking him whether he still had a beard. County said that he

did, a fact that Hannum confirmed in person a few days later.

{¶ 47} Lois Hood testified that Country and Beasley had been friends for

ten years, that Beasley was at one time married to her sister, and that he had visited

their farm in Caldwell three or four times. During the time that Country was in the

hospital, she said she saw Beasley around Caldwell accompanied by a young man.

On one occasion, in October, they came into Lois’s bar, and the young man had

mud all over his arm. Lois also recalled seeing Beasley at the hospital twice, once around September 12 and again on October 24. At the hospital, he gave his

telephone number to Lois as 330-256-7629.

{¶ 48} Police located Davis’s truck and trailer at the Caldwell Food

Emporium, where Davis said it would be. On November 8, investigators located a

shallow creek intersecting Don Warner Road where they found Davis’s black

leather ball cap.

November 2011: Tim Kern

{¶ 49} Tim Kern was divorced and the father of three boys. Around

October or November of 2011, he was working part-time at a gas station and was

either staying at a friend’s house or living in his car. Despite his troubles, he visited

his boys every day.

{¶ 50} Kern’s ex-wife, Tina Kern, and son, Nicholas Kern, both testified

that Kern was looking for jobs on Craigslist. On October 10, 2011, Kern responded

to a Craigslist ad for a farm caretaker. Nicholas drove his father to a job interview

at a Waffle House off Interstate 77 on November 9.

{¶ 51} Security video from the Waffle House shows Kern meeting for about

a half hour with a man who resembles Beasley. A few days later, Kern told

Nicholas that he got the job, that it was in Cambridge, and that he planned to leave

right away.

{¶ 52} Kern left on November 13. The night before, Tina notarized a

transfer of title for his Buick, because Tim said he had to title his car in his

employer’s name. The employer’s name was not added to the transfer. Tina and

Nicholas never saw Kern again.

November 2011: Richard Beasley

{¶ 53} Beasley asked Don Walters for help with a broken-down Buick he

said he had bought. The two men drove to Canton, where the Buick was parked at

a sandwich shop. In the glove box, Walters found a vehicle registration in the name

of Kern. Beasley gave the Buick’s title to Walters, asking him to scrap the vehicle using his own name and identification. Beasley told Walters that he had a farm in

Noble County, and he invited Walters to see the farm after he scrapped the Buick.

{¶ 54} On November 15, Beasley left four voicemail messages on Walters’s

phone, imploring Walters to help him move the car before it was towed. Walters

testified that Beasley was calling about the Buick and its title. At trial, Walters

identified photographs of the Buick. Tina Kern identified those same photographs

as her ex-husband’s Buick.

November 2011: The Investigation Concludes

{¶ 55} On November 14, FBI agents and local law enforcement returned to

the scene of the Davis shooting to search the woods. An empty, hand-dug hole,

about 80 inches long and a couple feet deep was found approximately 175 feet from

the road. An agent with the Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation

(“BCI”), Steven Burke, testified that his first impression on seeing the hole was that

it was a grave. The hole was 100 to 150 feet from where Davis’s hat had been

found earlier.

{¶ 56} The next day, search dogs alerted investigators to an area of

disturbed soil. Below, they found David Pauley’s mostly naked body. On

November 25, roughly 80 feet from the open unused grave, searchers found another

shallow grave containing Ralph Geiger’s naked body.

{¶ 57} On November 15, Bais told investigators that his girlfriend had

found a note at their house to call “Dutch;” the note gave a telephone number of

330-245-8961. Based on cellular-tower data, police determined that the phone

associated with that number was last used near Gridley Avenue. Investigators

independently tracked Beasley to Gridley Avenue through his Craigslist

correspondence with Kaufman.

{¶ 58} Officers arrested Beasley on November 16 and executed a search

warrant at the Kaufman residence on Gridley. Among the items in Beasley’s

bedroom was a collection of NASCAR trading cards, an ammunition box, and a green cooler containing a model train and books on trains, all of which had

belonged to David Pauley. Agents also found mail there addressed to “Ralph

Geiger,” including an envelope from PNC Bank dated September 30, 2011. They

found a receipt for emergency medical services provided to Ralph Geiger on

February 25, 2011. And they recovered four prescription pill bottles with Geiger’s

name on them and two pill bottles with Beasley’s name on them.

{¶ 59} After Beasley’s arrest, Joyce Grebelsky received a letter addressed

to “Joyce Grebowski,” a misspelling seen in one of the “Ralph Geiger” job

applications. The return address identified the sender as “Chris Star” in the Summit

County Jail. Grebelsky did not know a “Chris Star.” She believed the letter was

from Beasley. Inside were a three-page handwritten letter and a map. The letter

read:

Joyce,

Get your truck from Reeves & scrap it. Keep $100 and put

the rest on my books.

I need for you to go to the Gridley house where I lived at

night and go into the back yard, in the rear corner by the garage

under some leaves is 2 laptop cptrs, get them & destroy them, then

take them apart and trash them.

In the front corner of the backyard, between the house &

drive is a wallett under leaves, get that wallett & destroy the

contents, if there are $ left its yours.

Do not tell anyone about this & never even hint on a phone,

write me a letter & use the phrase “sunny day” if it goes allright, or

“rainy day” if the cptrs are gone, I might be able to call you by TDay, If so, you can say the code words on the phone, If you haven’t

got it yet, just say “average day.”

It is very important this gets done, I mean, critical.

[HAND-DRAWN MAP]

Look forward to a good report, will write soon,

R

The map showed a house and backyard, with an X by the garage labeled “cptr” and

a second X labeled “wallet.”

{¶ 60} Grebelsky contacted authorities about the letter on November 25, After receiving Penny Kaufman’s consent to search the premises on Gridley

Avenue, FBI agents found a wallet containing a driver’s license, Social Security

card, birth certificate, and other personal documents in the name of Ralph Geiger

under a downspout in the northwest corner of the property. And in the southwest

corner, under a pile of leaves, they found an Acer laptop computer and a Dell laptop

computer.

{¶ 61} BCI computer-forensic specialist Allan Buxton examined the

laptops. On the hard drive of the Acer he found a deleted account in the name of

Rick Pauley (David’s brother) as well as documents authored by Rick Pauley.

{¶ 62} The Dell computer and a computer taken from Joe Bais’s home had

both been used to access the [email protected] e-mail account with a

password. And in the Dell’s browser history, Buxton located the text of an ad

offering a handyman job on a secluded property in Ohio. The ad appeared on a

website, Akron-Canton.backpage.com, on November 1, 2011. The e-mail address

that placed the ad was [email protected]. All outgoing traffic from

[email protected] ceased when Beasley was arrested. The Acer

computer had also been used to access that e-mail account.

{¶ 63} On November 25, agents and a cadaver dog located Tim Kern’s

body, fully clothed, in a shallow pit in a wooded area near a vacant Summit County

mall. Kern’s driver’s license and Social Security card were found on his body.

{¶ 64} Licking County Deputy Coroner and Chief Pathologist Charles

Jeffrey Lee performed autopsies on David Pauley’s and Ralph Geiger’s bodies. Dr.

Lee testified that Pauley and Geiger were each killed by a single gunshot to the

head. Dr. Lee estimated that Pauley had been dead two to three weeks, but he could

not be certain.

{¶ 65} Summit County Chief Medical Examiner Lisa Kohler performed an

autopsy on Kern’s body. Dr. Kohler determined that he suffered five gunshot

wounds to the head.

{¶ 66} Law-enforcement officers arrested Brogan Rafferty on November

They searched his bedroom and found a briefcase containing, among other

items, a sawed-off shotgun, an Iver Johnson .22 long rifle semiautomatic pistol, a

box of ammunition, and some loose shotgun shells. According to ballistics expert

Jonathan Gardner, the bullets recovered from Kern’s body could have been fired

by the Iver Johnson pistol but he could not conclusively say that they were.

{¶ 67} However, the Iver Johnson pistol was not used to shoot the other

victims. Scott Davis was shot with a .32 caliber bullet, most likely fired from a

revolver. The bullet that killed Ralph Geiger was a .38 caliber bullet. The bullet

recovered from Pauley was an intermediate caliber, either .32 or .38. Gardner

testified that the bullet recovered from Pauley’s body was not fired by the Iver

Johnson or by the same weapon that killed Geiger, but he could not exclude the

possibility that the same weapon was used to shoot Davis and Pauley. In Gardner’s

opinion, therefore, a minimum of three guns were used in the crimes.

{¶ 68} When he was arrested, Beasley was carrying a phone that had been

activated on November 9, just days after the Davis shooting. This phone was not

the same one authorities used to track his location to Gridley Avenue. In Beasley’s

room at Gridley Avenue, they found two more cellphones, one of which was first

activated on October 30.

{¶ 69} Investigators linked five other prepaid cellphones to the crimes, none

of which was ever recovered.

Cellphones

a. The prepaid 4914 phone

{¶ 70} TracFone is a prepaid cellphone service. On July 30, 2011, an

unknown subscriber activated the phone number 330-289-4914 (the “4914 phone”)

through TracFone. The phone was last used on September 3, 2011.

{¶ 71} During the four weeks it was used, there were calls between the 4914

phone and phones used by Geiger, Rafferty, Walters, and Bais. On August 7, the

day before Geiger left for Caldwell, his phone received a call from the 4914 phone.

Between August 7 and 9, there were ten calls between the 4914 phone and

Rafferty’s cellphone. On the night of August 8 and into the early hours of August

9, 2011, while Geiger and two other men were checked in at the Caldwell Best

Western, six calls were placed from the 4914 phone that originated in close

proximity to that hotel.

b. The prepaid 7629 phone

{¶ 72} When Beasley visited Country Hood in the hospital, he told Lois

Hood that his phone number was 330-256-7629 (the “7629 phone”). That number

matched a prepaid phone that was activated on October 4, 2011. Phone records

documented calls between the 7629 phone and phones used by Walters, Grebelsky,

and Rafferty. It was also the contact number for the Craigslist ads posted from Joe

Bais’s computer using the e-mail address [email protected]. And Davis,

Dan DeWalt, George Brown, Kern, and Pauley all sent e-mails to

[email protected] responding to the Craigslist ad for a farm caretaker.

c. The prepaid 1804 phone

{¶ 73} A prepaid phone with the number 330-310-1804 (the “1804 phone”)

was first activated on August 30, 2010. Phone calls from the 1804 phone were

placed to the phones of Pauley, Davis, and Rafferty. Phone records show that on

October 21, 22, and 23, while Pauley was traveling to Ohio, four calls occurred

between Pauley’s phone and the 1804 phone. And on October 23, the day that

Pauley disappeared, a call occurred between his phone and the 1804 phone when

both devices were in the Marietta area.

{¶ 74} Beginning on October 27, there were multiple calls between the

1804 phone and Scott Davis’s cellphone. The last outgoing call on the 1804 phone

was to Davis’s phone on the morning that Davis was shot.

d. The prepaid 8961 phone

{¶ 75} A prepaid phone with the number 330-245-8961 (the “8961 phone”)

was activated on August 3, 2011. Six voicemail messages that were left for Walters

from Beasley came from this number. Walters identified that number as belonging

to “Dutch.” It was also the contact number placed on the gun tag at Smitty’s Gun

Shop. A call was placed from the 8961 phone to Smitty’s on November 10, 2011,

four days after the attempted murder of Davis.

{¶ 76} In the days surrounding Pauley’s death (October 21 through 23),

there were ten contacts between the 8961 phone and Rafferty’s phone. On October

22, the night before Pauley disappeared, the 8961 phone was in an area east of

Akron, as determined by the cellphone towers activated by its use. On the

following afternoon, it was in Guernsey County, directly north of Noble County,

where Pauley was killed, and appeared to be traveling north.

{¶ 77} There were also calls between the 8961 phone and Rafferty’s phone

in the days leading up to Kern’s death, November 8 through 13. On the day that

Kern disappeared, a call was placed from the 8961 phone to Rafferty’s cellphone

at 5:23 a.m.

e. The prepaid 5353 phone

{¶ 78} A prepaid phone with the number 234-738-5353 (the “5353 phone”)

was activated on November 6, 2011. The subscriber listed for the 5353 phone was

Jack Bell, One Main Street, Akron. The owner of the office building at that address

did not recall anyone by that name working there.

{¶ 79} Between November 8 and 13, multiple contacts occurred between

the 5353 phone and Tim Kern’s cellphone. At 11:15 a.m. on November 9, a call

was placed from the 5353 phone in the vicinity of the Waffle House near Interstate

77 at the precise moment that the Waffle House’s surveillance video showed

Beasley placing a call. After a call to Kern was placed from the 5353 phone on the

morning of November 13, the 5353 phone was never used again to make an

outgoing call.

‘They Were Candidates For Death’: ‘Craigslist Killer’ Lured Men With Bogus Job Ad Then Shot Them

Serial killer Richard Beasley preyed upon vulnerable men who became his victims. Another became his accomplice. BY JOE DZIEMIANOWICZ

In the fall of 2011, Scott Davis, 48, moved from South Carolina back to Ohio, where he looked forward to a new job as a live-in caretaker.

In exchange for $300 a week and a two-bedroom trailer for housing, as posted in an ad on Craigslist, Davis’s duties included watching over “a 688 acre patch of hilly farmland.” Davis needed a fresh start and this seemed like a promising opportunity, according to “Mastermind of Murder,” airing Sundays at 8:30/7:30c on Oxygen.

On November 6, 2011, Davis went to a Noble County restaurant to meet his employer, who called himself “Jack.” Alongside Jack was a teenager he introduced as his nephew.

Davis later rode with the two to a wooded area. He then got out of the car with Jack to survey the surroundings. But Davis, who walked in front of his new boss, heard a click, a sound that may have been made by a gun misfiring. He turned around as Jack shot him through the elbow.

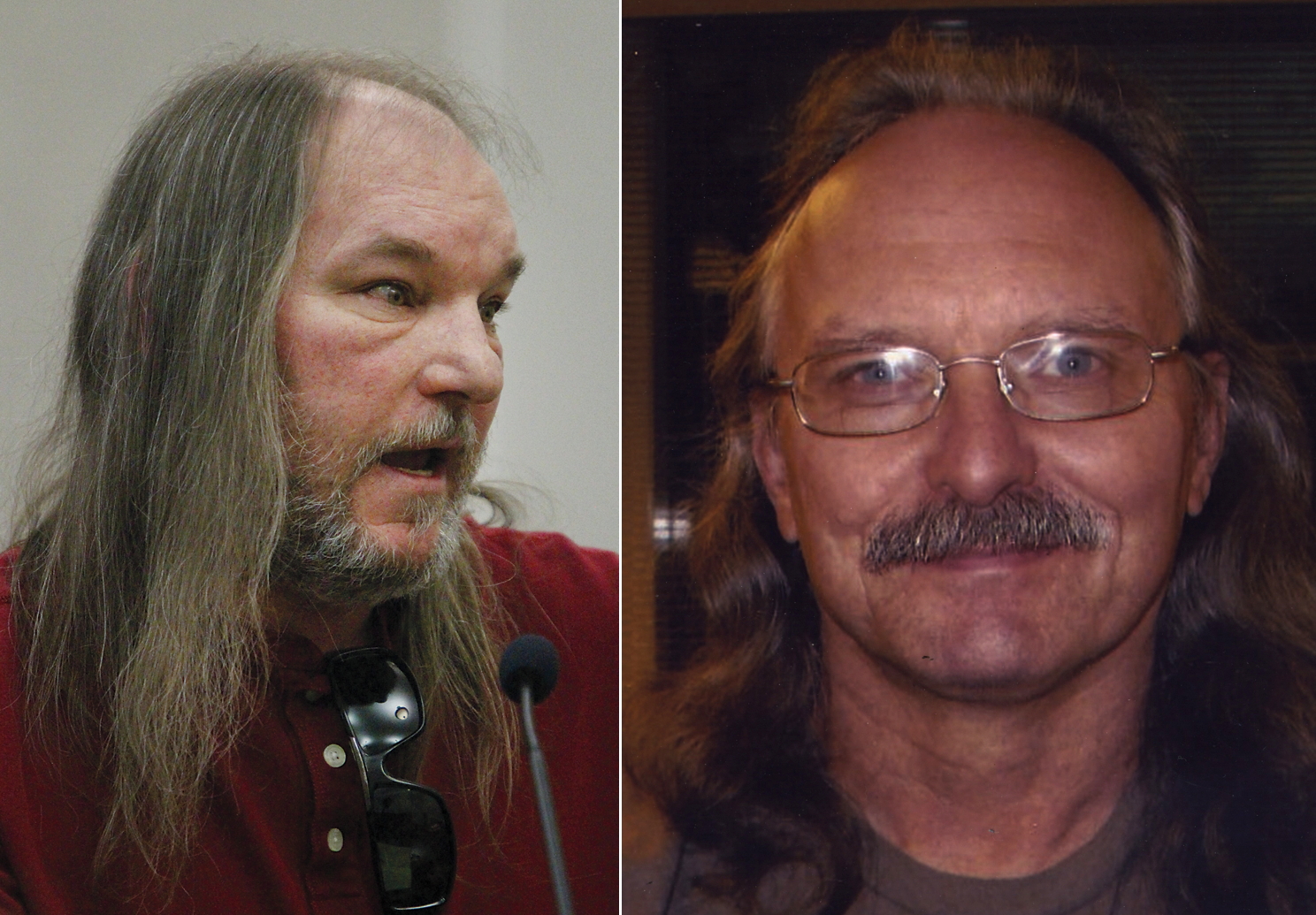

Richard Beasley and Brogan Rafferty

Bleeding and in pain, Davis ran for his life. He hid for seven hours in the middle of nowhere before making it to a house where the owner called 911.

While Davis was treated at the hospital, police searched for the shooter by reviewing security footage at the restaurant where the meeting took place.

Scott Davis

Five days later, as news of the shooting incident spread, police received a call from Debra Bruce. Her twin brother, David Pauley, 51, of Norfolk, Virginia had responded to an ad that sounded identical to the one Davis was duped by.

Police noted Davis and Pauley were about the same age and theorized that there could be a pattern forming. They considered the possibility that the shooter was interested in a certain type of victim: middle-aged men with relatively few family ties.

In fact, they would later discover that a woman in her 20s who answered the ad in October said she never heard back about it, CBS News reported in 2011.

Police searched for leads in the area where Davis had been shot. He told officials that he had lost his ball cap when he fled. If they found the hat there could be clues nearby.

It took two days to find the cap, according to Detective Sergeant Jason Mackie. They also made a chilling discovery near it: a freshly dug grave that presumably had been prepared for Davis’ body.

The search didn’t turn up any sign of Pauley, but authorities suspected that he may have been buried in the vicinity. A reinforcement crew and cadaver dogs were called in.

David Pauley

The search turned up the body of a man who had been shot in the back of the head. Pauley’s sister was able to identify the victim as her brother by a bracelet, according to “Mastermind of Murder.”

The body count escalated. Investigators found the remains of a third victim they couldn’t immediately identify.

Mackie reached out to the FBI to help trace who placed the Craigslist ad. Work by the cyber term led to the home of Joe Bais in Akron, Ohio.

When questioned by authorities, Bais denied placing a Craigslist ad. He added that he had a tenant who rented his basement space and used his computer and internet service. He knew that man as “Dutch,” who was eventually identified as Richard Beasley, 52.

A search of the Bais home where Beasley had stayed revealed prescription pill bottles with the name Ralph Geiger on them. The unknown body found in the woods where Davis was shot was confirmed to be Geiger’s.

Ralph Geiger

Investigators would learn that to avoid returning to prison in Texas, Beasley decided to go on the lam and change his identity. He assumed Geiger’s name as one of a number of aliases.

Davis confirmed images of Beasley as the man who shot him. The teenager who Beasley said was his nephew was actually Brandon Rafferty, 16, of Akron. Beasley had taken Rafferty under his wing.

Investigators interviewed the adolescent, who soon refused to speak without an attorney. Although Rafferty wouldn’t talk, police executed a search warrant on his house where they found a briefcase containing what Mackie called a “killing kit” filled with weapons.

They also found a disturbing poem on his computer dated August 16, 2011. “We took him out to the woods on a humid summer’s night … The loud crack echoed and I didn’t hear the thud.” It described the murder of Geiger.

Investigators theorized that Rafferty’s troubled home situation and lack of parental guidance helped make him vulnerable to falling under Beasley’s sway. Beasley was known for manipulating people to get what he wanted from them.

Beasley “is and always has been a snake oil salesman,” assistant prosecutor Jon Baumoel told producers.

Over time Beasley groomed Rafferty and was able to forge a relationship in which they were committing crimes together.

As a manhunt was underway for Beasley, who was now being referred to as the Craigslist killer, police caught a break. Not knowing that Bais had been in touch with authorities, Beasley left a message and a phone number with him.

Using that number, police tracked Beasley using phone tower signals and arrested him on November 16.

In another police interview Rafferty told authorities that men who responded to the bogus jobs were called “candidates.”

“They were candidates for death,” said Mackie.

A fourth victim, Timothy Kern, 47, died from a gunshot to the head on November 13, 2011. Kern’s body was found in the woods behind a mall in Akron on November 25.

Timothy Kern

When offered a deal that would have enabled him to get parole when he was middle-aged, Rafferty passed on it. He refused to turn on Beasley.

Rafferty was convicted of three counts of aggravated murder. In 2013 he was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole.

Beasley received the death penalty in 2013. In 2020, Beasley was resentenced because of a procedural error during his first sentencing, the Akron Beacon Journal reported. The overall result remained unchanged. He was again “sentenced to death and to multiple consecutive sentences for his other crimes.”

Murder by Craigslist

A serial killer finds a newly vulnerable class of victims: white, working-class men.By Hanna Rosin

SEPTEMBER 2013 ISSUE SHARE

Wanted: Caretaker For Farm. Simply watch over a 688 acre patch of hilly farmland and feed a few cows, you get 300 a week and a nice 2 bedroom trailer, someone older and single preferred but will consider all, relocation a must, you must have a clean record and be trustworthy—this is a permanent position, the farm is used mainly as a hunting preserve, is overrun with game, has a stocked 3 acre pond, but some beef cattle will be kept, nearest neighbor is a mile away, the place is secluded and beautiful, it will be a real get away for the right person, job of a lifetime—if you are ready to relocate please contact asap, position will not stay open.

Scott Davis had answered the job ad on Craigslist on October 9, 2011, and now, four weeks later to the day, he was watching the future it had promised glide past the car window: acre after acre of Ohio farmland dotted with cattle and horses, each patch framed by rolling hills and anchored by a house and a barn—sometimes old and worn, but never decrepit. Nothing a little carpentry couldn’t fix.

Davis rode in the backseat of the white Buick LeSabre; in the front sat his new employer, a man he knew only as Jack, and a boy Jack had introduced as his nephew, Brogan. The kid, who was driving the car, was only in high school but was already a giant—at least as tall as his uncle, who was plenty tall. Jack was a stocky, middle-aged man; Davis noticed that he’d missed a couple of spots shaving and had a tattoo on his left arm. He was chatty, telling Davis about his ex-wife, his favorite breakfast foods, and his church.

Davis, 48, had left his girlfriend behind in South Carolina, given away the accounts for his landscaping business, and put most of his equipment in storage. He’d packed his other belongings—clothes, tools, stereo equipment, his Harley-Davidson—into a trailer, hitched it to his truck, and driven to southeastern Ohio. He’d told everyone that he was moving in part to help take care of his mom, who lived outside Akron and whose house was falling apart. Moving back home at his age might seem like moving backward in life. But the caretaker job he’d stumbled across online made it seem more like he’d be getting paid to live free and easy for a while—a no-rent trailer plus $300 a week, in exchange for just watching over a farm with a few head of cattle outside the town of Cambridge. Jack had reminded him in an e‑mail to bring his Harley because there were “plenty of beautiful rural roads to putt-putt in.”

Jack and Brogan had met Davis for breakfast at the Shoney’s in Marietta, where Jack had quizzed his new hire about what he’d brought with him in the trailer. Davis boasted that it was “full from top to bottom.” After breakfast, Davis followed Jack and Brogan to the Food Center Emporium in the small town of Caldwell, where he left his truck and trailer in the parking lot, to be picked up later. Jack told Davis that the small road leading to the farm had split, and they’d have to repair it before bringing the truck up. They’d been driving for about 15 minutes, the paved road giving way to gravel, and then the gravel to dirt, while Davis watched the signal-strength bars on his cellphone disappear.

On a densely wooded, hilly stretch, Jack told his nephew to pull over. “Drop us off where we got that deer at last time,” he said, explaining to Davis that he’d left some equipment down the hill by the creek and they’d need to retrieve it to repair the road. Davis got out to help, stuffing his cigarettes and a can of Pepsi into the pockets of his jean jacket. He followed Jack down the hill, but when they reached a patch of wet grass by the creek, Jack seemed to have lost his way and suggested they head back up to the road. Davis turned around and started walking, with Jack following behind him now.

Davis heard a click, and the word fuck. Spinning around, he saw Jack pointing a gun at his head. Where we got that deer at last time. In a flash, it was clear to Davis: he was the next deer.

Davis instinctively threw up his arms to shield his face. The pistol didn’t jam the second time. As Davis heard the crack of the gunshot, he felt his right elbow shatter. He turned and started to run, stumbling and falling over the uneven ground. The shots kept coming as Davis ran deeper into the woods, but none of them hit home. He ran and ran until he heard no more shots or footsteps behind him. He came to the road and crossed it, worried that if he stayed in the open he’d be spotted by his would-be killer. He was losing a lot of blood by now, but he hid in the woods for several hours, until the sun was low, before he made his way back to the road and started walking.

Jeff Schockling was sitting in his mother’s living room, watching Jeopardy, when he heard the doorbell. That alone was strange, as he’d later explain on the witness stand, because out there in the boondocks, visitors generally just walked in the front door. Besides, he hadn’t heard a car drive up. Schockling sent his 9-year-old nephew to see who it was, he testified, and the kid came back yelling, “There’s a guy at the door! He’s been shot and he’s bleeding right through!” Schockling assumed his nephew was playing a prank, but when he went to the door, there was the stranger, holding his right arm across his body, his sleeve and pant leg soaked with blood. The guy was pale and fidgety and wouldn’t sit down at the picnic table outside. But he asked Schockling to call 911.

Sheriff Stephen Hannum of Noble County arrived after about 15 minutes. He would later describe Davis as remarkably coherent for a man who had been shot and was bleeding heavily. But what Davis was saying made no sense. He claimed that he’d come to the area for a job watching over a 688-acre cattle ranch, and that the man who’d offered him the job had shot him. But Hannum didn’t know of any 688-acre cattle ranches in Noble County—nothing even close. Most of the large tracts of land had been bought up by mining companies. Davis kept going on about a Harley-Davidson, and how the guy who shot him was probably going to steal it. The sheriff sized Davis up—middle-aged white guy, puffy eyes, long hair, jean jacket, babbling about a Harley—and figured he was involved in some kind of dope deal gone bad. Hannum made a few calls to his local informants, but none of them had heard anything. Then he located the truck and trailer in the Food Center Emporium parking lot, and they were just as Davis had described them. “It was beginning to look,” Hannum later recalled, “like Mr. Davis truly was a victim rather than whatever I thought he was at the beginning.”

Davis wasn’t the only person to answer the Craigslist ad. More than 100 people applied for the caretaker job—a fact that Jack was careful to cite in his e-mails back to the applicants. He wanted to make sure that they knew the position was highly sought-after. Jack had a specific type of candidate in mind: a middle-aged man who had never been married or was recently divorced, and who had no strong family connections. Someone who had a life he could easily walk away from. “If picked I will need you to start quickly,” he would write in his e-mails.

Jack painstakingly designed the ad to conjure a very particular male fantasy: the cowboy or rancher, out in the open country, herding cattle, mending fences, hunting game—living a dream that could transform a post-recession drifter into a timeless American icon. From the many discarded drafts of the ad that investigators later found, it was clear that Jack was searching for just the right pitch to catch a certain kind of man’s eye. He tinkered with details—the number of acres on the property, the idea of a yearly bonus and paid utilities—before settling on his final language: “hilly,” “secluded,” “job of a lifetime.” If a woman applied for the job, Jack wouldn’t bother responding. If a man applied, he would ask for the critical information right off the bat: How old are you? Do you have a criminal record? Are you married?

Jack seemed drawn to applicants who were less formal in their e-mail replies, those who betrayed excitement, and with it, vulnerability. “I was raised on a farm as a boy and have raised some of my own cattle and horses as well,” wrote one. “I’m still in good shape and not afraid of hard work! I really hope you can give me a chance. If for some reason I wouldn’t work out for you no hard feelings at all. I would stick with you until you found help. Thank you very much, George.”

If a candidate lived near Akron, Jack might interview him in person at a local Waffle House or at a mall food court. He’d start by handing the man a preemployment questionnaire, which stated that he was an equal-opportunity employer. Jack and the applicant would make small talk about ex-wives or tattoos, and Jack, who fancied himself a bit of a street preacher, would describe the ministry he’d founded. He’d ask about qualifications—any carpentry experience? ever work with livestock?—and provide more details about the farm. Jack explained that his uncle owned the place, and he had six brothers and sisters with a lot of kids and grandkids running around, especially on holiday weekends and during hunting season. The picture Jack painted was of a boisterous extended family living an idyllic rural life—pretty much the opposite of the lonely bachelor lives of the men he was interviewing.Schockling went to the door, and there was the stranger, holding his right arm across his body, his sleeve and pant leg soaked with blood.

If the interview went well, Jack might tell the applicant that he was a finalist for the job. But if the applicant gave any sign that he did not meet one of Jack’s criteria, the meeting would end abruptly. For one candidate, everything seemed on track until he mentioned that he was about to get married. Jack immediately stood up and thanked him for his time. George, the man who’d written the e-mail about being raised on a farm, told Jack that he’d once been a security guard and was an expert in martial arts. He figured this would be a plus, given that he’d have to guard all that property when no one else was around. But the mood of the interview immediately changed for the worse. Jack took the application out of George’s hands before he even finished filling it out and said he’d call him in a couple of days. If George didn’t hear anything, he should assume that “someone else got it.”

Scott Davis (left) and David Pauley (right), two of the men who had the misfortune of answering the Craigslist ad placed by the mysterious “Jack”

David Pauley was the first applicant who met Jack’s exacting criteria. He was 51 years old, divorced, and living with his older brother, Richard, in his spare bedroom in Norfolk, Virginia. For nearly two decades, Pauley had worked at Randolph-Bundy, a wholesale distributor of building materials, managing the warehouse and driving a truck. He married his high-school sweetheart, Susan, and adopted her son, Wade, from an earlier marriage. For most of his life, Pauley was a man of routine, his relatives said. He ate his cereal, took a shower, and went to work at precisely the same times every day. “He was the stable influence in my life,” says Wade. “I grew up thinking everyone had a nine-to-five.”

But Pauley grew increasingly frustrated with his position at Randolph-Bundy, and finally around 2003 he quit. He bounced around other jobs but could never find anything steady. He and Wade often had disagreements, and in 2009 he and Susan got a divorce. Now he found himself sitting on his brother’s easy chair, using Richard’s laptop to look for jobs. Mostly he’d find temp stuff, jobs that would last only a few weeks. Sometimes he had to borrow money just to buy toothpaste. He got along fine with Richard and his wife, Judy, but their second bedroom—with its seafoam-green walls, frilly lamp shades, and ornate dresser—was hardly a place where he could put up his poster of Heidi Klum in a bikini or start enjoying his post-divorce freedom.

Pauley was cruising online job opportunities when he came across the Craigslist ad in October 2011. Usually Pauley looked for jobs only around Norfolk. But his best friend since high school, Chris Maul, had moved to Ohio a couple years earlier and was doing well. He and Maul talked dozens of times a day on the Nextel walkie-talkies they’d bought specifically for that purpose. If Maul, who was also divorced, could pick up and start a new life, why couldn’t Pauley?

And the Craigslist job sounded perfect. Three hundred dollars a week and a rent-free place to live would solve all Pauley’s problems at once. On top of that, his brother, an ex-Navy man, was always pestering Pauley to cut his long hair before job interviews. With a gig like this, who would care whether he had long hair—the cattle? Pauley sat down and wrote an e-mail to Jack.

Well about me, I’m fifty one years young, single male, I love the out doors, I currently live in virginia have visited ohio and i really love the state. Being out there by myself would not bother me as i like to be alone. I own my own pick up truck so hauling would not be a problem. I can fix most anything have my own carpentry tools.

If chosen i will work hard to take care of your place and treat it like my own.

I also have a friend in Rocky River, Ohio. Thank you, David.

A few days later, Pauley got an e-mail back from Jack saying that he had narrowed his list down to three candidates, “and you are one of the 3.” Jack asked his usual questions—was Pauley married? had he ever been arrested for a felony?—and told him that if he was chosen, he’d have to start immediately.

Richard remembers his younger brother being energized in a way he hadn’t seen in months. Pauley called Jack several times to see whether there was anything else he could do to help him decide. Jack promised that he’d call by 2 p.m. on a Friday, and Pauley waited by the phone. When 2 o’clock came and went, he told his brother, “Well, I guess the other person got chosen above me.”

But early that evening, the phone rang. When Pauley got on the line, Richard recalls, his whole face lit up.

“I got it! I got the job!” he yelled as soon as he hung up. He immediately called his friend Maul on the walkie-talkie and started talking a mile a minute. He swore that this was the best thing that had ever happened to him and said he couldn’t wait to pack up and go. To Maul’s surprise, he found himself in tears. For the past few years he’d been worried about Pauley, whom he’d always called his “brother with a different last name.” Maul remembers, “It was like, maybe this is the turning point, and things are finally going the right way.” They made a promise to each other that on Pauley’s first weekend in Ohio after settling in, Maul would bring down his hot rod and they’d drive around on the empty country roads.

Next Pauley called his twin sister, Deb, who lives in Maine. She told him that she hated the thought of him sitting alone on some farm for Christmas and made him promise that he’d come visit her for the holidays. He told her that his new boss was a preacher and said he felt like the Lord was finally pointing him toward the place where he might “find peace.”

That week, Pauley went to the men’s Bible-study group he’d been attending since he’d moved into Richard’s house. For weeks he’d been praying—never to win the lottery or get a girlfriend, always for steady work. Everyone there agreed that God had finally heard his prayers.

The church gave Pauley $300 from its “helping hands” fund so that he could rent a U-Haul trailer. He packed up all his stuff—his model trains, his books and DVDs, his Jeff Gordon T-shirts and posters, his Christmas lights, and the small box containing the ashes of his old cat, Maxwell Edison—and hit the road.

Pauley arrived at the Red Roof Inn in Parkersburg, West Virginia, on the night of Saturday, October 22, 2011. It was not far from Marietta, Ohio, where he was supposed to meet his new employer at a Bob Evans for breakfast the next morning. He called his sister, who told him that she loved him and said to call back the next day.

Then, just before going to bed, he called up Maul, who told him, “Good luck. As soon as you’re done talking to them tomorrow, let me know. Give me an exact location so I can come down Saturday and we can hang out.”

The next day came and went with no call from Pauley. Maul tried him on the walkie-talkie, but there was no response. He then called Richard and got the number for Pauley’s new employer, Jack, whom he reached on his cellphone. Yes, everything was all right, Jack told Maul. He’d just left Pauley with a list of chores. Yes, he would pass on the message when he saw him the next day. But a few more days went by without a call, so Maul dialed Jack again. This time Jack said that when he showed up at the farm that day, Pauley had packed all his things in a truck and said he was leaving. Apparently he’d met some guy in town who was headed to Pennsylvania to work on a drilling rig, and he’d decided to follow him there.

There was no way, Maul thought to himself, that Pauley would take off for Pennsylvania without telling him. The two men had been best friends since high school, when they’d bonded over their mutual distaste for sports and love of cars. Over the years they’d moved to different cities, gotten married, gotten divorced, but they’d stayed “constantly in touch,” Maul said.

They kept their walkie–talkies on their bedside tables and called each other before they even got up to brush their teeth in the morning. They talked, by Maul’s estimate, about 50 times a day. “Most people couldn’t figure out how we had so much to talk about,” Maul said. “But there’d always end up being something.” But after Pauley reached Ohio? Nothing.

Early in November, about two weeks after he’d last spoken to Pauley, Maul called his friend’s twin sister. Deb hadn’t heard from him either, and was also worried—a habit she’d honed over a lifetime. When she and her brother were 14, their mother got emphysema. Since their father had left the family and their older siblings were already out of the house, Deb quit school and, as she put it, “basically became David’s mother.” Years later, she moved to Maine with her second husband and Pauley stayed in Norfolk, but the twin bond remained strong.

By the time she received the concerned phone call from Maul, Deb had already spent several days sitting with her laptop at the kitchen table, in her pajamas, looking for clues to explain why she hadn’t heard a word from her brother. With a red pen and a sheet of legal paper, she’d made a list of places to call—the motel in Parkersburg, the U-Haul rental place—but she’d learned nothing from any of them. It wasn’t until Friday night, November 11, nearly three weeks after Pauley had left for Ohio, that she remembered something else: Cambridge, the town where he had said the farm was located. She typed the name into Google and found the local paper, The Daily Jeffersonian. She scrolled through the pages until she landed on this headline, dated November 8: “Man Says He Was Lured Here for Work, Then Shot.” There was no mention of the man’s name, but there was one detail that sounded familiar: he said he’d been hired to work on a 688-acre ranch. The article cited the Noble County sheriff, Stephen Hannum. Deb called his office right away.

After picking up Scott Davis five days earlier, Hannum and his team had been following up on his strange story, but not all that urgently. They had Davis’s explanation about the Craigslist ad, and they’d located security-camera footage from his breakfast meeting with his “employers.” But Deb’s phone call lit a fire under Hannum’s investigation. She told Jason Mackie, a detective in the sheriff’s office, that Pauley had talked with his friend Maul 50 times a day and then suddenly stopped. Although no one said it explicitly at the time, a sudden drop-off like that meant a missing person, and that in turn meant there might be a body.

The next day, a Saturday, the sheriff’s office called an FBI cyber-crimes specialist to help them get information about who had written the Craigslist ad. They also sent a crew with cadaver dogs back to the woods where Davis had been shot. One FBI agent would later recall the “torrential downpour” that day and the sound of coyotes howling. A few hours before dark, the investigators found a patch of disturbed soil overlaid with tree branches. They began digging with their hands, until they found blood seeping up from the wet earth and a socked foot appeared. The body they discovered was facedown, and one of the items they removed from it was a corded black-leather bracelet with a silver clasp. Mackie telephoned Deb and described the bracelet. Yes, it was her brother’s, she told them. The investigators also found a second grave, this one empty. They later learned it had been meant for Davis.

Now the investigators knew they were looking for a murderer. By early the next week, they had identified the man in the breakfast-meeting footage as a local named Richard Beasley. Additionally, the cyber-crimes specialist had received enough information from Craigslist to trace the IP address of the ad’s originating computer to a small house in Akron. When the investigators arrived at the house, its occupant, Joe Bais, said he’d never written any ads on Craigslist and he didn’t know anyone named Richard Beasley or Jack. But when they showed him a picture, he recognized the man who’d called himself Jack. It was someone he knew as Ralph Geiger, who until recently had rented a room from Bais for $100 a week. “Real nice guy,” Bais would later recall on the witness stand. “He didn’t cuss, didn’t smoke, didn’t drink … First Sunday he was there, went to church.” As it happened, Geiger had just left him a note with his new cellphone number. The landlord called Geiger and kept him on the line as investigators traced the call. On November 16, an FBI swat team arrested the man outside another Akron house, where he had been renting a room after leaving Bais’s place. The suspect’s name was, in fact, Richard Beasley. Although investigators didn’t know it yet, Ralph Geiger was the name of his first victim.

Tracking down the teenager who had been with Beasley/Jack when he drove Scott Davis out into the woods proved easier. Just as Jack had said, his name was Brogan, Brogan Rafferty to be exact, and he was a junior at Stow-Munroe Falls High School. A detective and an FBI agent drove to the school and interviewed Rafferty in the principal’s office, while another set of investigators searched his house. Rafferty later told his mother that before he left school that day, he had found a girl he liked and kissed her, even though her boyfriend was nearby. He had been worried that he’d never see her, or anyone else from his high school, again. He was right to worry: that evening, police arrived with a warrant, and he was taken into custody.

Richard beasley, aka Jack, was born in 1959 and raised in Akron primarily by his mother, who worked as a secretary at a local high school, and his stepfather. He was briefly married and had a daughter, Tonya, who was about Rafferty’s age. Over the years, he worked as a machinist, but his job record was interrupted by spells in jail. He served from 1985 to 1990 in a Texas prison on burglary charges and, starting in 1996, another seven years in a federal prison for a firearms offense. When he went on trial for the 2011 Craigslist murders, the photo favored by newspapers made him look deranged, with wild eyebrows and hair and a crumpled mouth. But during the trial, with his white hair combed and his beard trimmed, he looked almost like Santa Claus, especially when he smiled.

In the mid-2000s, a dump truck hit Beasley’s car and he suffered head, chest, and spinal injuries. He had recently returned to Akron from federal prison, where, he told everyone, he’d found God, and he’d begun spending a lot of time at a local megachurch called the Chapel. After the accident, he started taking opiates for back and neck pain and stopped working steadily.

But Brogan Rafferty’s father, Michael, who knew Beasley from the local motorcycle circuit, told me that even before the car wreck, Beasley had been “lazy.” He was known as someone who always had “a little bit of an angle going,” like a “scam artist,” Michael Rafferty said. People in their motorcycle clubs knew Beasley had a criminal record, but to Michael Rafferty he seemed harmless, like he was “all talk.” Michael Rafferty said he’d never once seen Beasley lose his temper in the 20 years he knew him.

Beasley didn’t drink or smoke much, and he spent a lot of his free time at the Chapel, where he went to Bible study and worked in a soup kitchen. So when, at age 8, Brogan Rafferty said he wanted to start going to church on Sundays, his dad said it was okay for him to go with Beasley. It was only church, after all. And Michael Rafferty, a single parent who was working long shifts at the time, hated waking up early on Sundays anyway.

For the next eight years, Beasley was a regular presence in the Rafferty house on Sundays, coming by early to get his young charge, who’d be waiting in a slightly rumpled suit. Sometimes when he took Rafferty to church, Beasley would bring along his daughter, Tonya, or Rafferty’s half-sister Rayna, who was three years younger than Rafferty and shared the same mother but, like Rafferty, lived full-time with her own father. (Rafferty’s mother, Yvette, was a crack addict who didn’t have custody of her four children and was rarely around when they were young.) Beasley was a mentor to Rayna and her brother, Rayna recalls. After Bible study, he’d sneak them leftover donuts or take them to McDonald’s and talk to them about the importance of school or the danger of drugs. “The Bible is the key to peace of mind, and a road map to salvation,” he wrote in the Bible he gave Brogan.

Around 2009, Beasley founded what he told friends was a halfway house to help reform addicts, runaways, and prostitutes. Beasley would cruise the streets of Akron at night, picking up strays and bringing them back to the house. If they were in trouble with the law, he would vouch for them in court, saying they had turned their lives over to Christ. A few times, Rafferty asked Beasley whether they could go out and look for his mother, Yvette, who Rafferty always worried was in trouble.