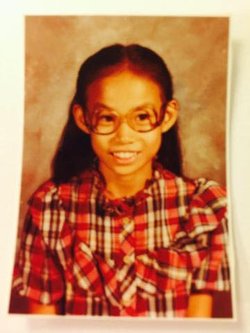

Victim: Sacha Thieszen, 12

Age at time of murder: 14

Crime location: Henderson, Nebraska

Crime date: September 17, 1987

Weapon: Wooden rod & .22-caliber pistol

Murder method: Beating on the head and shooting in the head and chest at close-range

Convictions: First-degree murder

Sentence: Life without parole (LWOP) later reduced to 70 years to life

Incarceration status: Incarcerated at the Tecumseh State Correctional Institution & eligible for parole in 2026

Summary

Thieszen murdered his adoptive sister by beating her with a wooden rod and shooting her at close range in the head and chest. He was convicted and sentenced to LWOP. His sentence was later reduced, giving him a chance to be paroled in 2026. Thieszen appealed his new sentence and the Nebraska Supreme Court upheld it.

Details

Thieszen murdered his adoptive sister Sacha by beating her on the head with a wooden rod and shooting her three times in the head and chest at close-range. Sacha’s 13-year-old sister found her body in the bathroom. Sacha’s shorts had been unbuttoned and unzipped.

Thieszen pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and using a firearm during a felony. He was sentenced to life with parole for the murder charge and 80 months to 240 months for the firearm charge. In 1996 he got another chance for a trial. This time, he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to LWOP, along with six to 20 years for the firearm charge. His sentence was later reduced to 70 years to life, giving him a chance to be paroled in 2026. Thieszen appealed to the Nebraska Supreme Court, arguing that his sentence was a “de facto life sentence” and was excessive and disproportionate. The Nebraska Supreme Court upheld the sentence.

Thieszen had been adopted by his family at the age of five. At age 12, he started displaying behavior problems. He was caught “spying” on his sisters while they bathed, he shot one of his mother’s chickens, he destroyed farm and school property, and he viciously kicked a fellow female student for no apparent reason. He also was given two years of probation in juvenile court for sexually molesting a younger foster child who was living with the family. Several of the killer’s classmates testified that Thieszen threatened to kill his entire family on numerous occasions.

Sources

Almost 20 years after murder, Thieszen family in shambles

LOSING A FAMILY MEMBER TO MURDER CAN CHANGE A PERSON. SOME FAMILIES CAN ALLOW EACH MEMBER TO HANDLE THE EMOTIONS IN HIS OR HER OWN WAY AND BECOME STRONGER. SOME FAMILIES FALL APART.

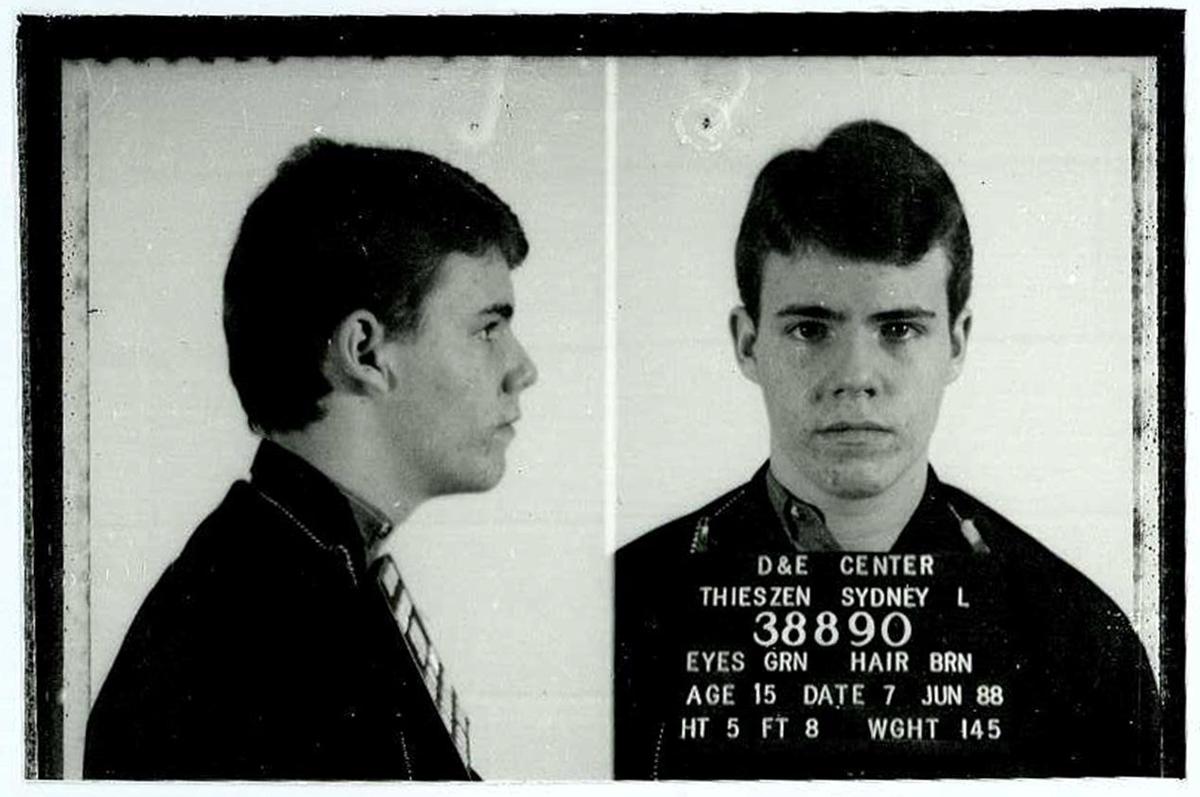

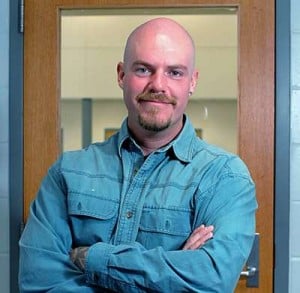

Sydney Thieszen at the Tecumseh State Correctional Institution. (LJS file)Enlarge Photo

Just so you know.

Losing a family member to murder can change a person.

Pain and fear and grief can move in, rearrange the furnishings of life, plop down in a too-soft chair and stay — for years and years, if not forever.

Some families can allow each member to handle the emotions in his or her own way and become stronger. Some families fall apart.

That’s what happened with the Thieszen family of Henderson. Twenty years ago, Sacha, 12, was killed by her 14-year-old brother, Sydney.

For Edwin and Joyce Thieszen, grief and fear seemed to evolve into terror, said Sydney and Sacha’s sister Sharon Hanke.

For Hanke, and her brother Shea, seeing the murderer’s face on the front page of the newspaper on Wednesday brought raw emotions — anger and grief — roaring back to the surface.

The story, which included an interview with Sydney Thieszen, detailed the efforts of an Omaha group to seek a law that would prohibit life sentences without the chance of parole for offenders younger than 18. Thieszen was convicted in 1988, and again in 1996.

The murder was brutal. He hit his sister in the head with a wooden rod, then shot her three times at close range in the head and chest. When she was found dead in an upstairs bathroom of the family home, her jean shorts were unbuttoned and unzipped.

Thieszen pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in 1988 and was sentenced as an adult to life in prison, with the possibility of parole in 1999. In 1996, he got another chance for a trial, which ended in a first-degree murder conviction and a sentence of life without parole.

Things came out in the 1996 trial that piled onto the family’s already raw emotions and fear, Hanke said. Friends testified Sydney Thieszen had told them he wanted to throw a plugged-in radio into his mother’s bath.

And he allegedly told investigators he had thought about killing all of his family members.

After that trial, Hanke said, her parents began to push away family and friends.

“I’ve had no contact (with them) in 10 years,” she said.

A few years ago, she heard they were beginning to sell their belongings. Then they disappeared.

“I never understood,” Hanke said.

“It’s an extreme reaction we don’t see very often,” said JoAnna Briggs, manager of the Lincoln Police Department’s victim-witness unit.

But fear and the feeling of betrayal can escalate and overcome people. They may begin to believe an inmate can somehow reach out from prison and harass or kill them. Or that he will get out and track them down.

Hanke said the turmoil changed who she was.

“I had to make a choice whether to be a victim — scared, depressed, angry — or to stand up and become stronger,” she said.

She and her brother Shea, who goes by a different name today, said they think about Sacha all the time and miss her.

The Thieszens adopted Sacha girl in 1977 when she was 18 months old. She was so malnourished she was about the size of a 9-month-old, Hanke said. She couldn’t speak and could barely feed herself.

Ten years later, the 5-foot-3 inch, 85-pound girl with long, dark hair and braces was enjoying life. She was quiet and shy on the edge of her teenage years, and experiencing her first crush.

Then-13-year-old Shea found his sister’s body late that September day in 1987 after returning from the farm field with his dad. They had noticed the family van was missing as they drove up, and his dad had taken off to look for Sydney.

“The sight of her laying in the bathtub with her pants unzipped, bullet holes in her chest, blood all over except her extremely pale skin that used to be a golden tan, has never left my mind,” he said. “I can see it as clear as the day I found her.”

After her death, Shea left the family.

“If there ever was some kind of bond between the parents and children, it was a fragile one at best,” he said. “The bond was mostly between the children. In my case, I was closest to Sacha.”

He went his own way, landing in a few foster homes and eventually Boys Town.

“I did not have contact with other family members until the last trial and keep in contact only with Sharon,” he said.

Sydney was 5 when he came to the family in 1978 from foster homes and a traumatic childhood with his biological mother. He was a wonderful, lovable boy, Hanke said, outgoing and intelligent.

At 12, his behavior changed, both at home and at school. He became moody, troubled and unhappy, Hanke said.

“I know my parents didn’t think it was anything more than a teenage thing,” she said. “They had no idea he was capable of that kind of violence.”

Hanke attended every day of the 1996 trial.

“There was a lot of stuff I didn’t know, and didn’t want to know,” she said.

She doesn’t understand why her brother committed the crime, and she knows she never will.

But seeing his face on the front page of the paper last week threw her.

“I now have a new mission in life — to fight this proposed bill and educate the community about what my family has had to endure since

“Sacha was brutally taken away from us at the hands of Sydney Thieszen,” she said. “I am appalled there is even the smallest chance that he might have an opportunity for parole.”

The crime was heinous, said Shea, and Sydney should never be allowed to return to society. He cannot be reformed, he said.

Hanke said her brother chose his violence and he needs to be held accountable.

“I am honestly afraid he would hurt someone again,” she said. “I agree that the (juvenile justice) system needs fixing, but the solution is not to set young murderers and rapists free.”

Just so you know.

Reach JoAnne Young at 473-7228 or [email protected].

442 N.W.2d 887 (1989)

232 Neb. 952

STATE of Nebraska, Appellee, v. Sydney L. THIESZEN, Appellant.

No. 88-605.

Supreme Court of Nebraska.

July 21, 1989.

On September 17, 1987, 14-year-old Sydney L. Thieszen shot and killed his 12-year-old sister, Sacha L. Thieszen. Sydney Thieszen was originally charged with first degree murder and use of a firearm in the commission of a felony. On January 7, 1988, Thieszen filed a motion to transfer his case to juvenile court. Following an evidentiary hearing, this motion was denied by the district court for York County on February 2.

On May 3, 1988, pursuant to a plea bargain, an amended information was filed charging Thieszen with second degree murder and use of a firearm in the commission of a felony. Guilty pleas were accepted by the court. On June 7, the appellant was sentenced to life imprisonment on the second degree murder charge and 80 months to 240 months on the firearm charge, the latter sentence to be served consecutively to the first. It is from these sentences that Thieszen appeals, alleging the district court abused its discretion in failing to transfer his case to juvenile court and in imposing an excessive sentence with respect to the firearm charge.

A brief history of the life of the appellant, Sydney Thieszen, is necessary to illuminate the circumstances under which this distressing crime took place. Sydney was born November 13, 1972, with the name of Michael Anthony Firuccia. He never knew his biological father, who left home when Sydney was 2 years old. Sydney was raised by his natural mother, an alcoholic, who often subjected him to physical abuse when she was intoxicated. This abuse included an attempt to drown him at age 2, an attempt to burn his eyes out with a cigarette lighter, and an attempt to run his hands through a meat grinder.

The parental rights of the natural mother were subsequently terminated by the juvenile division of the York County Court. After spending time in various foster homes, Sydney finally went to the Thieszen home as a foster child in 1979 and was formally adopted by the family in 1983, at the age of 11. At this time, the Thieszens changed his name from Michael Anthony Firuccia to Sydney Lamont Thieszen.

At the time of Sacha’s death, only four of the Thieszens’ six children were still living at home. Of those four children, only one, Stefani, was a natural child of the Thieszens. The other three children, Sydney, Shea, and Sacha, were all adopted.

The Thieszens are religious and strictly adhere to the Mennonite faith. Their home is very structured, with discipline including physical spankings with a hose or a belt. Until age 12, Sydney exhibited no behavior problems, and in fact was an outgoing, apparently well-adjusted, intelligent child. A good student, he enjoyed participating in science fair projects, working on the farm with his dad, and hunting. At age 12, a *889 drastic change in his behavior occurred. He began to earn poor grades and to seriously misbehave at home and at school. Sydney was caught “spying” on his sisters while they were bathing, shooting one of his mother’s chickens, destroying farm and school property, and viciously kicking a fellow female student for no apparent reason. In view of these activities, the Thieszens began therapy with Sandra Hale Kroeker, a certified social worker, in an attempt to return Sydney to more normal behavior.

Throughout the time Sydney was living in the Thieszen home, a number of other foster children also resided there. In December 1986, it was discovered that Sydney had been sexually molesting a younger foster child who was living with the Thieszens. As a result of this activity, a charge was filed in the juvenile division of the York County Court, and after admitting the offense, Sydney was placed on 2 years’ probation. Until the murder of Sacha, Sydney performed well on probation, demonstrating respect both for his probation officer and the legal system in general.

Exactly what happened on September 17, the day Sydney killed Sacha, is unclear. In his statement made to officers who arrested him in Kansas a few days after the crime, Sydney indicates that he had no premeditated plan to kill his sister. When he came home from school on September 17, Sydney contends, he found a note on the kitchen table from his mother to his father, indicating that he had done something wrong and that his father was to “take care of it with the hose.” After discovering the note, Sydney decided to run away. He went to his brother’s room and took a .22-caliber pistol to take with him on his “escape,” and tucked it into the waistband of his pants. He and his sister Sacha were in the kitchen area of the home, when she began to argue with him regarding his intent to run away. He hit Sacha in the head with a dowel. Sacha, bleeding from the head, ran upstairs to the bathroom. Sydney followed her up the stairs and looked in the bathroom at Sacha. She was leaning over the sink, bleeding, and crying. On impulse, he pointed the pistol at the back of her head and shot her once. She fell to the floor. He picked her up, placed her in the bathtub, and shot her twice more. He then took the family van and drove to Salina, Kansas.

When questioned, Sydney could give no reason for the crime. He repeatedly stated he did not know why he did it, but indicated that the reason he shot her while she was in the bathtub after shooting her in the head was because he did not want her to “suffer” in case the first shot had not killed her.

The Thieszens dispute this account of the events of September 17. They contend that subsequent to the murder, a number of Sydney’s classmates told the Thieszens that on numerous occasions Sydney said he was going to kill his whole family. At the hearing regarding the motion to transfer to juvenile court, these classmates testified that although Sydney had threatened to kill his family, they did not take his threats seriously because Sydney was the type of child to say things in order to draw attention to himself. Nonetheless, the Thieszens indicate that they are very frightened of Sydney and what he might do to them if he is released.

A number of psychological experts testified on the motion to transfer to juvenile court. Kroeker, who began counseling Sydney during the seventh grade, testified that Sydney had a conduct disorder and could not be diagnosed as an individual with a personality disorder because his personality was not yet fully formed. Kroeker testified that in an adult penal system, incarceration would tend to reinforce the violent, self-protective stance that Sydney takes in situations in which he feels threatened, and further stated that the risks to society and to Sydney are substantial if he is placed in an adult facility. She suggested that the Lincoln Regional Center would be an appropriate place for Sydney to receive care, but because they would have *890 custody over him for only 4 years if admitted as a juvenile offender, she did not feel that the Lincoln Regional Center was the best place for Sydney, as this is not long enough to deal with the conduct disorder. She felt that it would take 6 to 10 years for successful rehabilitation.

Dr. David Kentsmith is a board-certified psychiatrist who practices in Omaha, Nebraska. He examined Sydney on October 2, 1987, and was called as a witness for the defense. Dr. Kentsmith stated that Sydney appeared to suffer from no apparent mental illness and was subdued and remorseful. He diagnosed Sydney as suffering from a conduct disorder. Further, Dr. Kentsmith testified that he diagnosed the event as an isolated, aggressive, unsocialized act. Dr. Kentsmith found Sydney treatable at this point in his life and stated that he would do best in a setting where everyone incarcerated is being treated. He testified further that the high risk offender program at the Lincoln Regional Center would provide an appropriate environment for Sydney.

Dr. William Logan also testified on behalf of Sydney. Dr. Logan is a psychiatrist experienced in dealing with juveniles that have been charged with serious criminal offenses. He agreed that Sydney was suffering from a conduct disorder and testified that Sydney was greatly troubled by what had occurred. Dr. Logan further investigated whether the Lincoln Regional Center would accept Sydney. He testified that the Lincoln Regional Center is specifically designed to treat individuals who have a conduct disorder problem. However, Dr. Logan stated that he could not guarantee that after treatment at the Lincoln Regional Center, Sydney would not be violent in the future. He also testified that the hospital phase of the therapy could probably be completed by the time Sydney turned 19, but he would need many years of individual outpatient psychotherapy, which he would have to pursue on his own.

The appellant claims that the district court abused its discretion in refusing to transfer his case to juvenile court. The State argues, first, that this claim was waived by entering a guilty plea following the juvenile court hearing and, second, that the district court was correct in denying the motion to transfer.

Due to our disposition of this cause, whether the appellant waived his challenge to the district court’s denial of his motion to transfer by entering a guilty plea is not an issue that needs to be resolved. Instead, we will focus on whether the district court erred in denying the appellant’s motion to transfer. The standard of review applicable to an appeal from a denial of a motion to transfer to juvenile court is abuse of discretion. State v. Ryan, 226 Neb. 59, 409 N.W.2d 579 (1987). In view of this standard, in order to reverse we must find that the district court abused its discretion in refusing to transfer this case.

In deciding whether to grant the requested waiver and to transfer the proceedings to juvenile court, the court having jurisdiction over a pending criminal prosecution must carefully consider the juvenile’s request in the light of the criteria or factors set forth in Neb.Rev.Stat. § 43-276 (Reissue 1988). State v. Ryan, supra; State v. Alexander, 215 Neb. 478, 339 N.W.2d 297 (1983).

Nebraska man who killed sister in 1987 has life sentence reduced

YORK, Neb. — She sat down in court Friday, took a trembling breath and gave an unimaginable accounting of loss to the man responsible for it.

Almost 30 years ago, Sharon Hanke’s 12-year-old sister, Sacha, was shot to death in her family’s farm home near Henderson. The revolver was wielded by her 14-year-old brother, Sydney.

The killing destroyed her family. Her siblings’ lives remain in shambles. Her parents, in hiding.

“How do you even wrap your head around the betrayal and the hurt of someone that you loved for years slaughtering your sister,” Hanke said through tears. “It makes you question your very existence and the trust of everyone around you.”

Sydney Thieszen sat across the courtroom, his eyes cast toward shackles around his wrists. Later, he stood and tried to explain the burden he has carried for 30 years in a prison cell.

“There’s not a day that goes by in my life that I don’t feel sorrow and remorse for what I did, taking the life of a precious little girl,” he said.

The two took turns speaking Friday in a York courtroom as Thieszen, now 44, asked for a reduction in his life prison sentence. He won the chance because of a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said juveniles who kill cannot receive mandatory life terms.

York County District Judge James Stecker agreed to reduce Thieszen’s sentence to 70 years to life. It gives Thieszen hope for parole after about nine years, a possibility that did not exist under his former sentence.

But the court flatly rejected Thieszen’s request for 40 years to something less than life.

“The crime was violent, brutal and utterly senseless,” the judge said.

The judge also expressed skepticism regarding Thieszen’s explanation of the killing: that he acted in a fit of panic after his sister threatened to call the police to thwart Thieszen from running away. Evidence showed that Thieszen admitted to investigators he had been thinking of killing his family and he had purchased a box of .22-caliber ammunition in the weeks before the shooting.

After the hearing, Thieszen’s lawyer, Jeff Pickens of the Nebraska Commission on Public Advocacy, said his client will appeal the decision as a “de facto life sentence.”

Corey O’Brien with the Nebraska Attorney General’s Office acknowledged that the defendant suffered horrific abuse during his first years of life, before he was taken in as a foster child and eventually adopted by the Thieszen family.

Abuse, however, does not excuse murder, O’Brien said.

“There are thousands of kids who come from situations much worse than what Sydney came from and they choose not to murder,” he said.

O’Brien asked the judge to give Thieszen not less than 80 years in prison. Afterward, he said the judge’s decision of 70 years to life was “just.”

The judge also left intact the original sentence of six to 20 years for a weapons conviction. Under the state’s good-time law, which cuts prison terms roughly in half, Thieszen would be eligible for parole after serving a little more than 38 years.

But if he does receive parole, he would remain under state supervision for the rest of his life.

In December, the Nebraska Supreme Court determined that Thieszen was entitled to a new sentence, citing the Supreme Court ruling that struck down laws requiring mandatory life terms for juveniles convicted of murder.

Nebraska had such a law on the books when Thieszen and 26 other juvenile killers were convicted. That law has since been replaced with one that requires judges to consider prison terms ranging from 40 years to life for juveniles convicted of first-degree murder.

In the case known as Miller v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that advances in brain research have shown that mental capacity does not fully develop until a person’s mid-20s. As a result, children have an “underdeveloped sense of responsibility, leading to recklessness, impulsivity and heedless risk-taking.”

The court also said that with treatment and education, juvenile offenders have a better chance at successful rehabilitation. For those reasons, laws that prevent judges from considering such factors when sentencing juveniles violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

With the resolution of Thieszen’s case, all but three of the juvenile killers in Nebraska who were given mandatory life terms have received new sentences, although most of those will not get out until they are retirement age. Several have obtained their releases or been paroled.

The Supreme Court has more recently said juveniles also cannot be given life terms unless the sentencing judge made a finding that the defendant is “irreparably corrupt.”

Pickens said the evidence clearly shows Thieszen is far from irreparably corrupt.

Thieszen has amassed more than 200 misconduct reports during his incarceration, but none has involved a violent act. Most are for using drugs or violating rules that wouldn’t result in tickets on the outside.

He is considered a low risk to reoffend by the psychologists who have interviewed him. He scored a 35 on the prison’s custody rating; it takes a 30 to qualify for work release, Pickens said. Prison evaluators have said he doesn’t need substance-abuse treatment or anger-management training.

He has a network of close friends who will help him on the outside, Pickens said. He would not try to return to York County where, judging by the letters sent to the judge, he is still regarded as a threat.

“Regardless of what happens here today, the rest of my life will be spent expressing my remorse for what I did through the constant efforts to add to the lives of those around me,” he told the judge.

But his sister said she never heard him express remorse before Friday. Although the family cut off contact with him after his arrest and conviction, in the years since he has never sent a letter asking for forgiveness.

His words mean less than nothing to her now, she said.

During her statement, Hanke wanted Thieszen to know something he probably never considered: She was the one who had to clean up the blood in the bathroom where their sister died after having been shot three times.

“Do you know what that does to a person?” she asked. “That is something I’ll never recover from.”

[email protected], 402-473-9587

Nebraska Supreme Court affirms sentence for man who killed sister when he was 14

In 1987, Sydney Thieszen committed a horrific crime as a 14-year-old.

Nebraska’s highest court said Friday it supported his resentencing last year from life without parole to a minimum of 70 years in prison. It provides him with a “meaningful and realistic opportunity to obtain release,” the judges said.

Thieszen was in his early teens in 1987 when he shot and killed his 12-year-old adopted sister Sacha in their home near Henderson. He first hit her with a wooden rod, and when she ran to the bathroom because of the bleeding, he followed and shot her in the back of the head. He put her in the bathtub, shot her twice more, then took off for Kansas in the family van. He was apprehended there days later.

He was charged with first-degree murder and use of a firearm to commit a felony. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and the firearm charge, and was sentenced as an adult to life in prison, with the possibility of parole in 1999.

Thieszen spent a year isolated in the York County jail after his conviction. He then went to an isolated room at the state Diagnostic and Evaluation Center in Lincoln when he was 15. A year later, he was released to the general population of adult inmates.

In 1996, he was granted another chance for a trial. But this time the state charged Thieszen with first-degree murder and use of a firearm, which ended in a conviction and a sentence of life without parole.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mandatory life without parole sentences were unconstitutional for juvenile offenders.

The Nebraska Legislature passed a law that allowed juveniles convicted of first-degree murder to be sentenced to a minimum 40 years to life, with eligibility for parole after 20 years. It also allowed judges to continue to use discretion on life sentences for young people, saying they could sentence a youth to more than the minimum.

The bill grew out of the state’s need to act on the federal court ruling that the courts would have to consider mitigating factors in sentencing, such as age, maturity and home environment, including previous abuse of the juvenile.

The district court vacated Thieszen’s life sentence and set a hearing for a new sentencing.

At Thieszen’s mitigation hearing last year, the district court heard evidence he had been severely abused by his biological mother until the age of 4, when he was placed in several foster homes. When he was 9, he was adopted by Edwin and Joyce Thieszen, people with strong religious beliefs who had three biological children and two other adopted children.

“Although Edwin and Joyce offered a stable and structured environment, it may not have been a nurturing one,” the court said.

According to testimony, when he was 13, Thieszen was diagnosed with a conduct disorder, and just after he turned 14, the family learned he had been sexually molesting one of the family’s foster children. His relationships at home and school had deteriorated, and he reportedly talked of killing his adoptive mother and other family members.

Psychiatrists testified that adolescent brains are characterized by novelty-seeking, risk-taking, poor judgment and increased submission to peer pressure. They think in the moment and lack the ability to see long-term consequences. Early trauma and high levels of stress impact brain development, and corporal punishment, like that said to be used by his adoptive parents, could make a previously abused child more reactive.

The psychiatrists said a mental health evaluation of Thieszen showed no signs of mental illness or antisocial behavior in prison, and that he was at low risk for future acts of violence. From the age of 18, he’d had no sex-related misconduct reports or charges. Thieszen did report during the evaluation he’d had physical intimacies with female staff members while he was incarcerated.

A corrections officer testified Thieszen did not cause trouble and was respectful to officers and inmates.

He expressed remorse, regret and sorrow for his crime.

In 2007, in an interview with the Journal Star, Thieszen said he couldn’t explain why he killed his sister because he didn’t understand it himself. He said he was 18 or 19 before he realized the enormity of what he had done.

“The realization, it’s always there. It follows me. It’s ahead of me. It’s all around me,” he said in that interview.

Also in 2007, Sharon Hanke, a biological daughter of Edwin and Joyce Thieszen, told the Journal Star that after Sacha’s murder, her family fell apart. Her parents began to push away family and friends and eventually sold their belongings and went into hiding.

Hanke said at the time that she and her brother, Shea, who was one of three adopted into the family, thought about Sacha a lot, and missed her. The Thieszens had adopted Sacha in 1977 when she was 18 months old.

She said at the time that Sydney Thieszen should never be allowed to return to society, and she was appalled there was even the smallest chance he might have an opportunity for parole.

Shea, who went by a different name in 2007, said in an interview Sacha was the family member to which he was closest. He was 13 when he found his sister’s body that day in 1987.

“The sight of her laying in the bathtub with her pants unzipped, bullet holes in her chest, blood all over except her extremely pale skin that used to be a golden tan, has never left my mind,” he said. “I can see it as clear as the day I found her.”

After her death, he left the family and kept in touch only with Hanke, he said.

After last year’s hearing, York County District Judge James Stecker sentenced Thieszen, then 44, to 70 years to life, giving him a chance at parole in 2026. And he kept in place a sentence of six to 20 years on the weapons conviction.

Thieszen appealed the sentence, saying it was excessive and disproportionate, and a de facto life sentence without parole.

On Friday, the Nebraska Supreme Court affirmed the sentence, saying the district court did not abuse its discretion in imposing it.