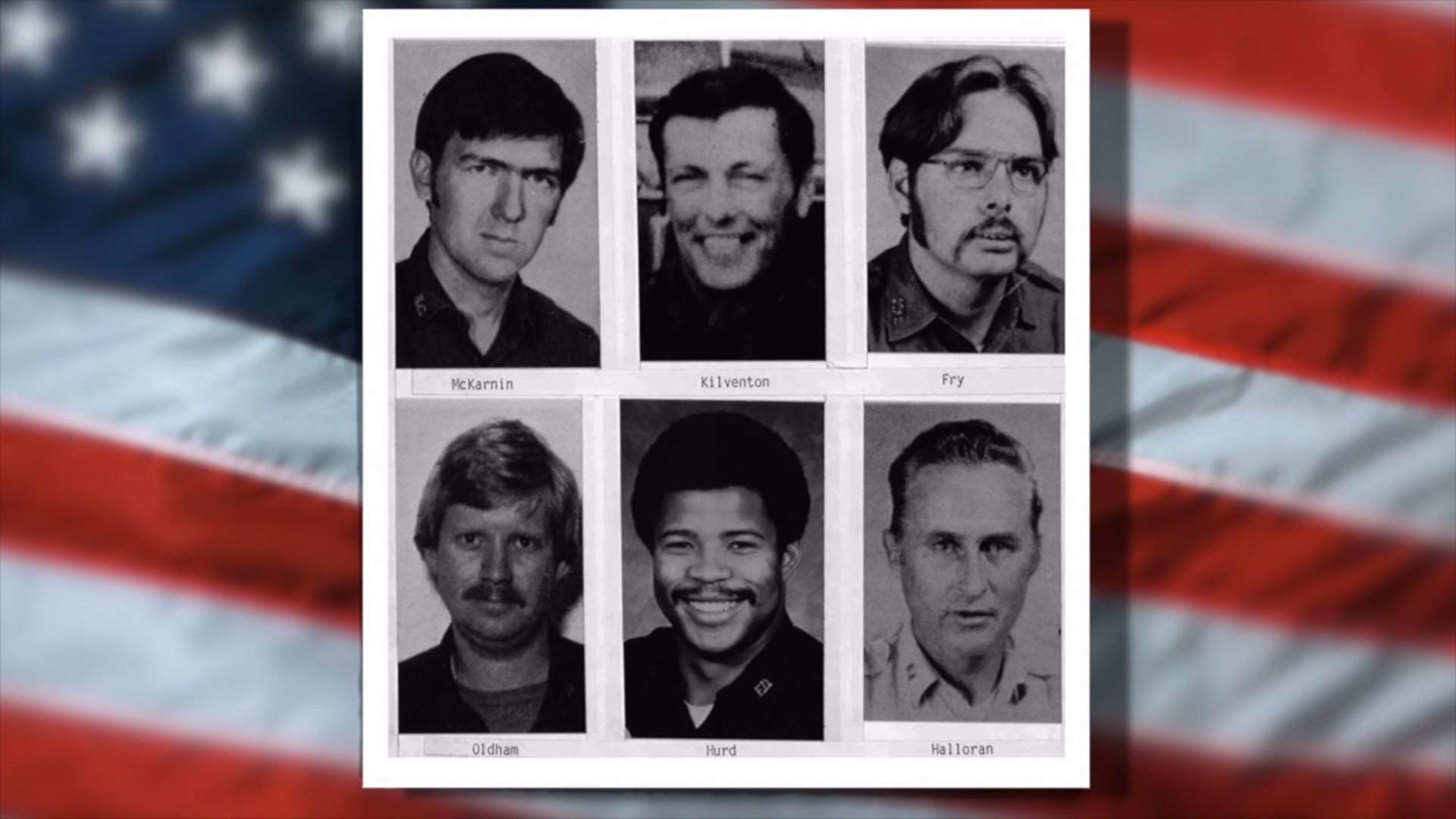

Victims: Captain Gerald Halloran, 57, Captain James Kilventon Jr., 54, Luther Hurd, 31, Michael Oldham, 32, Robert McKarnin, 42, & Thomas Fry, 41

Age at time of murders: 17

Crime date: November 29, 1988

Crime location: Kansas City, MO

Partners in crime: George Sheppard, Earl Sheppard, Darlene Edwards, & Richard Brown

Crimes: Arson & mass murder

Weapon: Fire & explosives

Murder method: Explosion

Murder motivation: Diversion

Sentence: Life without parole (LWOP) later reduced to 20 years

Incarceration status: Released

Summary

On a late fall day in 1988, an explosion claimed the lives of six firefighters. The offenders were accused of setting fire to a tractor trailer containing 25,000 pounds of low-grade construction explosives so that they could steal tools to sell for drug money. A decade after the deadly explosion, they were convicted. Questions about the defendants’ guilt has been raised over the years. Sheppard has maintained his innocence. After Miller v. Alabama, Sheppard was released.

Details

November 1988: Six KC Firefighters Killed in Ammonium Nitrate Explosion

Nov 1st, 2008

20 Years Later, New Investigation May Yield New Findings Into Cause

A hazardous materials explosion that occurred 20 years ago this month claimed the lives of six Kansas City, MO, firefighters. A nine-year investigation determined that the fire that caused the explosion was deliberately set and five people were convicted of the crime. New research, however, has led to the case being reopened with the possibility of those convictions being overturned.

On Nov. 29, 1988, at 3:40 A.M., the Kansas City Fire Department received a call for a fire at a highway construction site. The fire was reported by a security guard at the site to be in a small pickup truck, but in the background another security guard could be heard saying “the explosives are on fire.” Pumper 41 was dispatched to the site with a captain and two firefighters (in Kansas City, a fire apparatus with a pump is called a pumper). Dispatch cautioned Pumper 41 that there may be explosives at the site.

Pumper 41 arrived on scene at 3:46 and found two separate fires burning. A second pumper company was requested. Pumper 41 also requested that dispatch warn Pumper 30 of the potential for explosives at the site. Pumper 30 arrived on scene at 3:52. Four of the six firefighters on Pumpers 30 and 41, including both officers, had received hazardous materials training through National Fire Academy (NFA) field courses. Four had completed the NFA course “Recognizing and Identifying Hazardous Materials.” One of the firefighters and one company officer had also taken the NFA field course “Hazardous Materials Incident Analysis.” According to the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) Technical Report on the incident, “Both courses downplay the potential explosiveness of the type of blasting agent involved in this incident.” They go on to say that “this impression needs to be corrected.”

Because there were two separate fires at the site, the crew from Pumper 30 suspected arson and requested that the police be dispatched to the scene. Approximately five minutes after the arrival of Pumper 30, Pumper 41 requested a battalion chief be sent “emergency” to the scene. There was a great deal of confusion at the site as to whether there were explosives on site or whether the explosives were involved in the fires. Following the extinguishment of the pickup fire, Pumper 41 proceeded to the other fires to assist Pumper 30. A truck, a trailer and a compressor were on fire at 4:02. None of the vehicles or trailer appeared to be marked. There were no indications that the firefighters suspected any explosives were involved in the fires they were attempting to extinguish.

As it turns out, the “trailer” that was on fire actually was an explosives magazine. At 4:04, Pumper 41 contacted Battalion Chief 107, who had been dispatched to the incident. Pumper 41 indicated that “Apparently, this thing’s already blowed up, Chief. He’s got magnesium or something burning up here.” At 4:08, 22 minutes after Pumper 41 arrived and 16 minutes after Pumper 30 arrived, the magazine exploded, killing all six firefighters assigned to Pumper 41 and Pumper 30.

Battalion Chief 107 and his driver were just arriving on scene and stopped about a quarter-mile from the explosion. They received minor injuries when the windshield of their vehicle was blown in. Following the first explosion, the battalion chief ordered firefighters to withdraw from the area and a command post was set up at a safe distance from the site. Approximately 40 minutes after the first explosion a second blast occurred, followed by several smaller explosions. It is likely that the actions of the battalion chief prevented additional deaths and injuries.

Both explosions left large craters. The crater from the first explosion was approximately 80 feet in diameter and eight feet deep; the second blast left a crater about 100 feet in diameter and eight feet deep. It was reported by the Kansas City Fire Department that the first explosion involved a split load of materials in the trailer/magazine. One compartment held 3,500 pounds of ammonium nitrate/fuel oil (ANFO) mixture. The rest of the contents were 17,000 pounds of ANFO mixture with 5% aluminum pellets. The second trailer/magazine contained about 1,000 30-pound “socks” of ANFO mixture with 5% aluminum pellets. (In comparison, the Oklahoma City bombing involved 5,000 pounds of ammonium nitrate.) Pumper 41 was damaged beyond recognition by the explosion. Pumper 30 received significant damage as well, but could still be identified as a fire department vehicle.

Circumstances that likely compounded the danger existing at the construction site included the following:

- The dispatcher was told of the presence of explosives, but not what the explosive materials were, where they were located or that the explosives were on fire. In retrospect, dispatchers should get as much information as they can about an incident from the caller. In this case, dispatchers were talking to security guards at the site who were reporting the fire and who might have had additional information.

- Dispatchers and 911 operators should have basic hazmat training so they can better understand what to ask of a caller. Check lists with questions to ask callers can be helpful to dispatchers in gathering information. Both pumper companies were told of explosives on the site by the dispatcher, but nothing specific. This was a State of Missouri highway construction site with explosives in magazines. The Kansas City Fire Department had not been involved in the blasting-permit process and was unaware of explosives on the site prior to the incident; nor did the department have jurisdictional authority over the site. State highway sites are not under city control regarding permits or inspections, according to the city attorney.

- The federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) has universal jurisdiction over explosives listed in its regulations, except during transportation, but does not ordinarily inspect or issue permits for sites. Local fire departments are almost always the first responders to fires and emergencies involving hazardous materials. Their personnel are immediately at risk at sites and yet do not always have regulatory control or guaranteed coordination from other agencies. The Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act (EPCRA), sometimes referred to as SARA, gives fire department authority to visit expected hazmat sites for the purpose of pre-planning responses. Help may also be obtained by the Local Emergency Planning Committee (LEPC).

- Trailers/magazines probably were not placarded or marked to indicate that explosives were present. They were not required by ATF or the Department of Transportation (DOT) to be marked when located on site. ATF believes that if the explosives are not marked, they are less susceptible to theft, vandalism or terrorism. DOT requirements for placarding and labeling of containers at the time of the explosion required them only during transportation, not at fixed sites. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standard for the Manufacture, Transportation and Storage of Explosives – 1985 (NFPA 495) at the time, in Section 6-4, 6 required “the local fire department be notified of the location of all magazines.” Section 6-85 also required posting of signs reading “Explosives – Keep Off.” While NFPA standards are not regulation or law unless adopted by local jurisdictions, they do provide a consensus of the accepted safe practices.

- Material safety data sheets (MSDS) were not readily available at the time of the explosion. Today’s MSDS clearly indicate that personnel should flee this type of fire.

- DOT’s Emergency Response Guide Book (ERG) in use at the time of the explosion was the 1987 edition. Had the responding firefighters or dispatchers known what type of explosives were present, they could have obtained information from the ERG. The 1987 ERG did not have a hazard-class listing at the top of the Orange Action Guide pages. It did, however, have a placard chart with three explosive placards shown on the chart that referred to Orange Guide 46. This guide advises personnel to clear an area of 2,500 feet in all directions if the explosives are on fire. It further stated that if the fire involves the explosives cargo, no attempt should be made to fight the fire. Unfortunately, the firefighters did not know it was cargo that was on fire, as there were no markings or placards on the containers or pickup truck. The 2008 version of the ERG contains hazard-class information at the top of the Orange Guide Pages so even if there are no placards or other markings and responders know that explosives are present, they can follow the instructions for the worst-case scenario and withdraw personnel. While there is no official ATF policy against placarding, there appears there was at the time a generally accepted practice in the field of removing DOT placards when not in transit.

As a direct result of the explosion and firefighter deaths, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) adopted regulations that require all transportation containers of hazardous materials to continue to be placarded and labeled per DOT requirements when the containers are in fixed use and storage until the product is used up and containers have been purged of residual product.

In 1989, the Kansas City Council passed an ordinance adopting the NFPA-704 Marking System. This fixed-site marking system identifies general hazards of materials at a facility, but does not give specific information about individual materials that may be present. The Kansas City Fire Marshal’s Office also implemented procedural changes to allow it to become aware of blasting material and blasting projects within its jurisdiction.

Also a direct result of the 1988 explosion, the Kansas City Fire Department’s Hazardous Materials Team was placed in service in 1989. Pumper Companies 30 and 41 and their personnel were lost in the explosion. The numbers 30 and 41 were added together to form the number for Hazmat 71 in honor of the firefighters killed in the explosion.

The investigation of the explosion and fire scene resulted in the determination that this was an arson fire. In 1997, following a nine-year investigation, five people were convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the firefighters’ deaths. All subsequent appeals were denied. However, there is a great deal of controversy surrounding the convictions and a recent investigation by Kansas City Star reporter Mike McGraw has shed new light on the case. New evidence may result in the vindication of the five people convicted. According to the Kansas City Star, a security guard who was on duty the night of the fire has told people on two separate occasions that she and a fellow guard set the truck fire as a part of an insurance scam. The daughter of one of the persons convicted gave false testimony, which weighed heavily on the jury’s decision to convict the five suspects. As a result of the Kansas City Star investigation, the U.S. attorney has decided to reopen the investigation into the persons responsible for setting the fires.

In addition to being memorialized at the city’s firefighters memorial in downtown Kansas City, the fire department has erected a memorial to the firefighters killed in the explosion located along U.S. Highway 71 at 87th Street, near the blast site. This and other hazmat incidents and fires across the country over the years have resulted in lessons learned that unfortunately also cost lives and resulted in injuries of firefighters. It is important to the memory of those brave men and women that we learn from those incidents so that they have not given their lives in vain. It is also important that all emergency personnel who respond to incidents have training in hazmat awareness. All explosive materials are dangerous when certain conditions exist. Since responders may not know what those conditions are, all explosives should be treated as the worst-case scenario. If it is known that explosives are present and may be involved in fire, withdraw to a safe location and do not attempt to fight any fires.

IN MEMORIAM

Captain Gerald C. Halloran, 57

Firefighter Thomas M. Fry, 41

Firefighter Luther E. Hurd, 31

Captain James H. Kilventon Jr., 54

Firefighter Robert D. McKarnin, 42

Firefighter Michael R. Oldham, 32

31 years ago today an explosion killed 6 Kansas City firefighters

by: Stephanie GraflagePosted: Nov 29, 2019

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — It’s been 31 years since an explosion claimed the lives of six Kansas City firefighters.

Thomas Fry, Gerald Halloran, Luther Hurd, James Kilventon Jr., Robert D. McKarnin and Michael Oldham – were killed in a massive early-morning explosion at a construction site near 71-Highway in southeast Kansas City. The explosions were ruled to be caused by arson at a construction trailer loaded with tens of thousands of pounds of explosives.

Kansas City Deputy Fire Chief James Dean was a rookie firefighter that November night.

“I remember waking up to the explosion, and the location that we were located at shook,” Dean told FOX4 during an interview last year.

Kansas City’s pumper trucks 30 and 41 had arrived at a 71 Highway construction site minutes earlier and found two separate fires in the early hours of November 29, 1988.

“We started hearing some of the radio traffic and didn’t sound good,” Dean recalled.

“Pumper 30 or Pumper 41, please answer,” a dispatcher said.

What the six responding firefighters didn’t know was the burning trailers contained tens of thousands of pounds of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil, volatile explosives being used in the highway construction.

“If we had known that, if they had known that, we wouldn’t have had six men lost,” Kansas City dispatcher Phillip Wall told FOX4 in a 1988 interview.

Click or tap here the full story including an interview with a convicted man who said he’s still seeking the truth .

Judge denies release for woman convicted in deaths of 6 KCFD firefighters

September 4, 2020

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — A federal judge has denied early release for a woman convicted in the 1988 deaths of six Kansas City, Missouri, firefighters.

Darlene Edwards’ attorneys argued in a motion last week that she should be released from prison with credit for her 23 years already served because she suffers from severe medical problems, including morbid obesity and diabetes.

In court filings obtained Friday, U.S. District Judge Fernando Gaitan Jr. denied the request to reduce her sentence under the compassionate release statute, which allows sentences to be reduced for “extraordinary and compelling” reasons.

In the ruling, Gaitan said that while the COVID-19 pandemic and Edwards’ deteriorating health rise to the level of “extraordinary and compelling” reasons, they do not justify early release “when weighed against” other factors.

“(T)he arson that Edwards was convicted of aiding and abetting took the lives of six firefighters when the trailer exploded and instantly killed the firefighters,” the ruling reads. “Edwards’ crime had a profound affect (sic) on this community and forever altered the lives of the fire fighters’ (sic) families.”

Edwards and four men were convicted in the deaths of firefighters Thomas Fry, Gerald Halloran, Luther Hurd, James Kilventon Jr., Robert McKarnin and Michael Oldham, who were killed in a November 1988 explosion at a construction site in south Kansas City.

Judge Denies Early Release To Defendant Convicted In Explosion That Killed Six Kansas City Firefighters

KCUR | By Dan MargoliesPublished September 4, 2020

Darlene Edwards, now 66, has been in prison for 23 years. She says she is obese, diabetic and requires assistance walking.

One of five co-defendants sentenced to life in prison without parole for the deaths of six Kansas City firefighters 32 years ago has lost her bid for compassionate release from prison.

U.S. District Judge Fernando Gaitan Jr. on Friday denied the request of Darlene Edwards, who argued that her age, underlying health conditions and risk of contracting COVID-19 were reasons to reduce her sentence to time served.

Edwards, now 66, has been in prison for 23 years. She says she is obese, diabetic and requires assistance walking.

Although Gaitan agreed that Edwards has serious health conditions and does not pose a danger to the community, he said the severity of her crime weighed against her early release.

“Edwards’ crime had a profound affect (sic) on this community and forever altered the lives of the firefighters’ families,” Gaitan wrote in a 10-page order. “So, while Edwards has shown that her deteriorating health and the COVID-19 pandemic are extraordinary and compelling circumstances … they do not justify granting Edwards’ motion for compassionate release.”

Under the compassionate release statute, a court may reduce the term of imprisonment if it finds that “extraordinary and compelling reasons” warrant a reduction.

Edwards and her co-defendants were convicted in 1997 in connection with an explosion at a highway construction site near U.S. 71 and 87th Street during the early morning hours of Nov. 29, 1988.

The five were accused of setting fire to a tractor-trailer containing 25,000 pounds of low-grade construction explosives. Their alleged plan was to create a diversion from an attempt to steal tools, which they hoped to sell for drug money. The trailer blew up and the resulting blast could be felt throughout the entire metropolitan area.

The Kansas City Fire Department sent two firetrucks to the scene. The first extinguished a burning pickup truck before joining the second pumper, where the storage trailer was on fire. When the trailer exploded, it instantly killed all six firefighters at the scene and ignited a second trailer filled with 30,000 additional pounds of explosives.

One of the convicted defendants, Bryan Sheppard, was released from prison in 2017 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that mandatory sentences of life without parole are unconstitutional for juveniles unless their individual circumstances are taken into account. Sheppard was only 17 at the time of the explosion.

Over the years, questions have been raised about the defendants’ guilt. A series of investigative reports in The Kansas City Star by the late Mike McGraw found that many of the witnesses had been coerced into testifying against them. The Justice Department in 2011 released a two-page summary of its review of the case concluding there was no “credible evidence” to support such a claim. But it also suggested other people may have been involved in the arson, although no others have been charged.

Convicted Arsonist Claims FBI Is Hiding Records on KC Tragedy

KANSAS CITY, Mo. (CN) — A man who spent 19 years in prison for a deadly arson fire in Kansas City, Missouri, sued the Department of Justice for information he says will prove his innocence — and the innocence of still-imprisoned co-defendants.

Bryan Sheppard was convicted of arson for a 1988 fire that killed six Kansas City firefighters. He was 17 at the time of the fire and sentenced to life in prison in 1997 along with four others, Richard Brown, Darlene Edwards, Frank Sheppard and Skip Sheppard.

Though three of these individuals remain behind bars, Skip Sheppard died in prison and Bryan Sheppard was released in 2015 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a juvenile may not be sentenced to life without parole.

Stephanie Sankar, an attorney with the firm Shook, Hardy & Bacon, brought a federal complaint on Dec. 15 for Bryan Sheppard against the Department of Justice. Alleging violations of the Freedom of Information Act, Sheppard claims that numerous federal agencies, including the FBI and the Bureau of Firearms, Tobacco and Explosives, improperly withheld a slew of documents to cover up misconduct in the investigation.

The lawsuit cites 19 trial witnesses who claimed, years after the trial, that “the federal investigators pressured them to lie. Others claimed their statements to the federal investigators were ignored because they did not align with those of other witnesses who were either coerced or incentivized with money or reduced jail time.”

Investigations by the Kansas City Star in 2008 and by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Mike McGraw in 2015 turned up a number of jarring discrepancies.

McGraw wrote for the online magazine Flatland that the federal government presented “no DNA evidence, no fingerprints, no admissions, no tell-tale tracks in the mud, no eyewitnesses.” McGraw claimed that the federal government has acknowledged that it never fully solved the crime said it shows no interest in finishing the job.

According to the government’s theory, the five defendants went to 87th Street along U.S. 71 around 3 a.m. the day after Thanksgiving, intending to steal tools from the construction site to sell for drug money. The fire they set was not intended to kill, but to serve as a diversion. They allegedly set a separate fire in a pickup truck owned by a security guard, which ignited a trailer filled with thousands of pounds of construction explosives. The trailer exploded, killing instantly six firemen, Gerald Halloran, James Kilventon, Robert McKarnin, Michael Oldham, Thomas Fry and Luther Hurd.

A memorial service for the men drew 15,000 people, and the city erected a Firefighters Fountain downtown in their honor, and for other firefighters..

“These explosions were heard up to 50 miles away and caused craters 100 feet in diameter and 8 feet deep,” the complaint states. “More than 1,300 businesses and individuals within a 10-mile radius would claim property damage from these explosions.”

None of the men who were convicted agreed to testify against each other despite offers of plea deals. Three allegedly passed polygraph tests.

But the complaint names 19 witnesses who say they were coerced. The summaries of their statements cover 1½ pages of the 19-page complaint. For instance:

“a. Joe Denyer claimed he testified at trial that he heard defendant Darlene Edwards admit she was near the construction site only because federal investigators offered to help him with legal problems while in jail;

“b. Beckie Edwards claimed she testified at trial that she heard the defendants planning the theft only because federal investigators threatened her with drug charges;

“c. Carie Neighbors claimed she testified at trial that she overheard defendants Bryan Sheppard and Richard Brown admit to the crime at a party, but only because federal investigators threatened to prosecute her for contempt and take away her child …

“e. Jerry Rooks claimed he testified at trial that Richard Brown admitted his involvement to him, but only because federal investigators threatened him with more prison time for violating his probation …

“i. Dave Dawson claimed he lied to investigators in exchange for help with his own criminal charge, but when he recanted they charged him with several robberies he claimed he did not commit …

“j. Mike DeMaggio claimed federal investigators threatened him with additional jail time if he refused to implicate the defendants.

“k. Johnny Driver claimed that federal investigators threatened to charge him with the arson if he refused to implicate Bryan Sheppard.”

The other witnesses tell similar stories, all detailed in the complaint.

After the Kansas City Star published the results of its investigation in 2008, the Department of Justice said it would reinvestigate. It concluded in 2011 that there was no credible evidence to support the newspaper’s allegations, or the imprisoned men’s actual innocence.

Sheppard requested a copy of the Department of Justice report in 2016. Of the 450 pages the Department of Justice found, it released only 3 in full and parts of 35 pages. The other 412 pages were withheld.

“This case is not about whether the Star’s allegations are indeed true or whether the five individuals convicted of the 1988 arson are actually innocent,” Sheppard’s complaint says. “But rather if the federal government agency reviewing the actions of its own investigators and prosecutors, should be allowed to decide unilaterally, without any public review or accountability, that the agency and its personnel have done nothing wrong.”

The Department of Justice declined to comment. Sheppard’s attorneys did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Sheppard wants to see the records, and an explanation for any records that the government says are exempt, plus attorney’s fees and costs of suit.

Behind the ruling: What the Bryan Sheppard release order says about the case

By Mike McGraw

MARCH 08, 2017

A federal judge’s decision last week to release a man serving a life sentence in the 1988 deaths of six Kansas City firefighters was, at least for some of the families of those men, a hurtful betrayal by the legal system.

For the families of the accused, it was the final arrival of justice long delayed.

And for both sides, it showed that decisions handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court can have wrenching and far-reaching effects on real people.

The decision may have an outsized impact on other Kansas Citians who remember the arson-fueled construction site explosion. The blast near 87th Street and Bruce R. Watkins Drive was so massive it cracked foundations, ruptured gas lines, broke windows and quickly elevated the firefighters to hero status.

At its core, the decision Friday by U.S. District Judge Fernando J. Gaitan to release defendant Bryan Sheppard — a juvenile at the time of the crime and a grandfather now — was based on a 2012 Supreme Court decision that bars automatic life sentences in such cases.

But Gaitan’s 22-page order in the case offers a deeper analysis of a high-profile 1997 prosecution that ended with the convictions of five defendants and has troubled many in the Kansas City legal community for two decades.

A measured jurist who denied an earlier appeal in this case, Gaitan acknowledges in his order some of the inconvenient facts that have surfaced since the convictions. That it took nearly a decade after the 1988 explosion to bring about those convictions, with most of that time spent on a theory that federal agents later abandoned, was lost on no one.

Gaitan’s order includes a discussion of over-reaching criminal statutes passed during America’s law-and-order era in the 1980s and 1990s — and that many on the left and the right now want to eliminate. And it acknowledges emerging brain science asserting that juveniles are too immature to be given life sentences.

But it can also be seen as a shot across the bow of a prosecution that has long been mired in controversy.

LAW AND ORDER

Over the years, the U.S. legal system has treated juveniles harshly, Gaitan noted in his order. But the “law and order” decades of the 1980s and 1990s, Gaitan quoted one commentator as saying, ushered in “an even coarser treatment of youth due to the rise in popularity of the myth of the juvenile ‘superpredator,’ … radically impulsive, brutally remorseless youngsters … who murder, assault, rape, rob, burglarize.”

Though the theories turned out to be wrong, Gaitan said others have noted that “cultural lore around the superpredator claim contributed to Congress enacting and President Clinton signing the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 …which, among other things, authorized the federal prosecution of juveniles as adults for certain crimes of violence.”

But the law slowly evolved, as it always does, and it finally caught up with science. The law now says juveniles should be treated differently because human brains don’t fully mature until age 18 or later.

The families of the fallen firefighters, who waited nearly a decade for closure in this case and then had to relive their grief in a weeks-long 1997 trial — and once again last week — strongly reject that notion.

But it is the basis for a 2012 Supreme Court decision, Miller v. Alabama, which found that life sentences for juveniles are in many cases a violation of the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

And that’s why Gaitan released Sheppard, the only one of the four surviving defendants who was under 18 at the time of the crime.

Gaitan found that Sheppard’s tumultuous upbringing by alcoholic parents, who were themselves parented by alcoholics, was a factor indicating immaturity and the idea that he could have easily been misled by the older defendants — primarily his two uncles.

Gaitan also noted that Sheppard’s “relatively few” criminal convictions and exemplary conduct in prison demonstrate that he falls within the category of the juvenile offender whose crime reflects what the courts call “unfortunate yet transient immaturity.” It does not indicate that he is the “rare juvenile offender whose crime reflects irreparable corruption.”

In the end, Gaitan’s decision rejected an argument by Assistant U.S. Attorney Paul Becker (the original prosecutor in the case) that Sheppard should serve the rest of his life sentence. But the judge didn’t sentence Sheppard to another 10 years or 20 years, as he could easily have done, and which some had expected.

Instead, he ruled that the 20-year sentence Sheppard had already served was sufficient. And in doing so, he meted out one of the shortest sentences on record so far in Miller vs. Alabama resentencing cases.

Decisions have been handed down in 16 of the 28 resentencing cases that have been brought on the federal level. Of those cases, two inmates were ordered to complete their life sentences, and the remaining 14 were resentenced to anywhere from 10 to 60 years.

Sheppard’s sentence of 20 years (or time served) was the second lowest of all those cases.

That’s what stunned both Sheppard’s family and the families of the fallen firefighters who packed the courtroom last Friday.

But why did Gaitan hand down such a ruling, sure to be unpopular with the still-grieving families? The rest of his opinion may offer some clues.

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

“There is no denying that the crime which the defendants were convicted of resulted in a tragic loss of six lives,” Gaitan prominently noted in his order.

Killed in the blast were Capts. Gerald Halloran and James Kilventon Jr. and firefighters Thomas Fry, Luther Hurd, Robert D. McKarnin and Michael Oldham.

But Gaitan said he couldn’t ignore the fact that the judge in the original 1997 trial “did not believe that the defendants intentionally with malice and forethought set out to kill the firefighters.”

In fact, he added that, according to the government’s own theory of the case, Sheppard and the others went to the highway construction site to steal tools and that they set the fires merely to cover up their crime.

That whole theory of the case has long been questioned on its face as making no rational sense.

Gaitan also noted that the trial judge in 1997 acknowledged there was no evidence that the defendants meant to lure the firefighters to their deaths, or that they had any idea the fire would cause an explosion.

They should have considered that, Becker and the grieving families argued. But like it or not, the issue of whether Sheppard and the others actually meant to kill anyone that night has always been an issue in the case, at least from a legal perspective.

Gaitan could have stopped right there, but he didn’t.

The elephant in the room during the resentencing hearing was evidence that has been emerging since before the trial even ended that all five defendants, who have consistently denied guilt, could have been wrongly convicted.

Gaitan said from the outset, in his earlier rulings in the case, that he would not allow Sheppard’s attorney to go there. But in his order, Gaitan went there on his own.

He noted there was no hard evidence in the case, and that Sheppard has consistently maintained his innocence. In fact, when the government suggested that Sheppard should acknowledge his role in the crime if he wanted a reduced sentence, he refused to do so.

Indeed, Sheppard had said publicly that he would not admit to a crime he did not commit, even if it meant he would serve another 40 years.

Gaitan also found it noteworthy that there was a “lack of evidence regarding Sheppard’s participation in the crime” and that several of the witnesses who testified against him have since recanted.

The judge also relied on earlier court statements showing that the government’s case was built partly on a confession by defendant Darlene Edwards and numerous witnesses who testified that the defendants — in private conversations with them — had admitted their guilt.

Years ago, Edwards recanted that confession, which had been made in the face of serious drug charges arranged by government agents as part of their investigation of the larger case.

As for the numerous witnesses who claimed that Sheppard and the others admitted involvement in the crime, Gaitan noted earlier findings that they were inconsistent and offered few details about the alleged role of each defendant.

He could have added that many of those witnesses had strong incentives to adopt the government’s theory in the case. One of them got a sentence reduction of 25 years after he testified.

Some of those same witnesses would later tell The Kansas City Star that they were pressured to lie — an assertion that a two-year federal investigation would later question.

No undue pressure was applied, the government said in its final report on the matter in 2011.

However, that investigation would also identify two new suspects in the case — in addition to the five in prison.

The Justice Department says those two new suspects helped commit the crime along with Sheppard and the others. But government officials have consistently refused to identify them. And Gaitan denied a request from Sheppard’s attorney, Cyndy Short, to release an unredacted version of the report that names them.

The U.S. attorney here, Tammy Dickinson, has consistently declined to discuss whether those new suspects were investigated or to speculate as to why the defendants — all of whom were serving life sentences until Friday — would refuse to name them.

Her spokesperson reasserted that position just this week.

As for Sheppard, Friday’s decision will not allow him to reclaim his good name. Indeed, he had no claim on one until he went to prison and straightened out his life.

But at least he can say that a federal judge has finally acknowledged — sort of — that there’s a chance he may be innocent. And it only took 20 years.