Victims: Rebecca Spencer, 27, Joan Heaton, 39, Jennifer Heaton, 10, and Melissa Heaton, eight

Age at time of murders: 13-15

Location of the crimes: Warwick

Crime dates: July 27, 1987–Rebecca’s murder; September 1, 1989–murders of the Heatons

Crimes: Home invasion, murder, triple murder, & murder of children

Weapon: Knife

Murder method: Stabbing–Rebecca was stabbed 58 times; Joan was stabbed 57 times; Jennifer was stabbed 62 times; and Melissa was stabbed 30 times

Sentence: Incarceration’s until 21st birthday for the murders (but given more time for additional crimes)

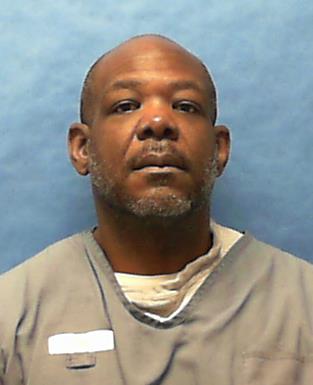

Incarceration status: Incarcerated at the Florida State Prison

Summary

In 1987, Price, then 13, invaded his neighbor Rebecca’s home and stabbed her to death, inflicting 58 stab wounds on the mother of two. Two years later, he invaded the home of the Heaton family, who were also his neighbors. Price, then 15, stabbed Joan and her young daughters to death, inflicting dozens of wounds on each victim. Price was tried as a juvenile and was sentenced to incarceration until his 21st birthday-the maximum sentence available. However, the serial killer has committed additional crimes, including violent crimes, and been sentenced to more time in prison. In 2004, he was transferred to Florida, where he remains incarcerated to this day.

Details

PROVIDENCE, R.I. (AP) – Craig Price was just 15 years old in 1989 when he confessed to the murders of four neighbors, crimes that terrified the state, triggered a new state law allowing for harsher treatment of young criminals and instantly transformed the baby-faced teenager into Rhode Island’s most notorious serial killer.

He was prosecuted as a juvenile and was supposed to be released in 1994, at the age of 21. But he remains locked up because of a series of new offenses committed behind bars and a 25-year criminal contempt sentence he received for defying a judge’s orders to undergo psychological testing.

Now Price, who is jailed in Florida and acts as his own lawyer, wants to return to Rhode Island next month to argue his latest appeal. He’s asking the state’s highest court to vacate his contempt sentence, calling it “unduly harsh and unconstitutional.” But Rhode Island’s corrections department is fighting Price’s request to appear in person, saying his transport from Florida for a 12-minute argument would cost taxpayers thousands of dollars and pose a safety threat. The attorney general’s office, which prosecuted Price, also opposes his bid.

“His criminal history includes four particularly brutal murders, extortion and blackmail, criminal contempt, and numerous violent assaults upon correctional officers,” Patricia Coyne-Fague, the corrections department’s chief lawyer, wrote in court papers. “He has a long history of violent assaults of those charged with keeping him in custody.”

Price was transferred out of state at his own request and is serving his sentence in Florida, where he has been disciplined for, among other offenses, assaulting prison guards and fighting with other inmates.

The arguments are scheduled for March 2 before the state Supreme Court. Spokesman Craig Berke said the court will decide whether it will hear from Price himself or whether it will rely instead on his written arguments.

“Now it’s in the court’s hands to decide what to do,” Berke said.

Price was 15 and living with his parents in Warwick’s Buttonwoods section when he was questioned by police in the killings of neighbor Joan Heaton and her two daughters, ages 8 and 10, who were strangled and stabbed with kitchen knives. Police found knives used in the killings in his backyard shed, and a sock print matched his feet. Price confessed to the killings and also admitted to the unsolved murder two years earlier of another neighbor, Rebecca Spencer, who was stabbed roughly five dozen times inside her house.

Though Price could have been sentenced to life without parole if he were an adult, state law at the time prevented him from being jailed past his 21st birthday. His case inspired a law change that allows juveniles to be prosecuted as adults and, when merited, receive life sentences.

Four days before his scheduled release in October 1994, he was convicted of extortion for threatening to kill a guard at the youth detention facility where he was being held. His lawyers complained that prosecutors were trumping up charges to keep Price locked up, but he was sentenced anyway to seven years in prison and, also that year, was found in civil contempt and given a one-year sentence for refusing to undergo a psychological exam.

Price continued to avoid psychiatric counseling at the advice of his lawyers, who were afraid the results of any testing could expose him to a harsher sentence. In 1997, he was convicted of criminal contempt for defying the judge’s orders. He was sentenced to 25 years, with 10 to serve and the balance suspended unless Price got into trouble or refused treatment.

“For five years, Craig Price said ‘go to hell,’” J. Patrick Youngs, the prosecutor in the case, said at his sentencing. Price, in his own speech, said he had since consented to the treatment he had initially resisted.

‘Into another world’

He thought before he slit the screen: Let the girls live.

Craig Price made two cuts, each four inches, in the wire window mesh and then reached two fingers inside and slid up the screen. He stepped out of his sneakers, and climbed up, out of the dark backyard and into the lasting nightmares of Rhode Island.

Fifteen-year-old Craig Price was high on marijuana and LSD. He just stood there at first, knife in hand, in his neighbor’s kitchen. The Warwick home of Joan Heaton and her daughters, Jennifer and Melissa, was dark.

As Price would one day write:

Craig Price stalked on his toes toward Joan Heaton’s bedroom.

There was no calm before the storm. I was coming with the straight storm, swift and deadly.

With his hand on her doorknob, he froze, not breathing.

Had he heard something?

A child’s hand reached through darkness toward Craig Price and felt that he was real.

The touch spread panic.

Panic gave way to anger, and anger gave way to a blinding fury. Some people say it, but I’ve actually seen it: I could actually see the color red cloud my vision . . . and the rage I felt was like a wave of heat that kept crashing on me and popping my ears.

As he held one of them down, Price stabbed his own finger.

The cut would betray him as the killer.

CRAIG PRICE slashed across the psyche of a state that night in 1989.

The Heatons were stabbed and beaten to death in a quiet suburb, in their home. For two weeks the crime went unsolved; many in Rhode Island went without sleep.

The killer’s arrest was nearly as shocking as the crime: the police accused a neighborhood kid with the body of a man and the face of a child. Fifteen-year-old Craig Price admitted to killing the Heatons.

Under questioning, he confessed to another unsolved murder: Two years earlier, in 1987, he had killed his neighbor Rebecca Spencer.

Rhode Islanders could not fathom the teenager who murdered four people in two nights of killing two years apart, all before he was old enough to drive. He became the state’s great enigma, explained with a shrug, a shiver and a word:

Monster.

For half his life, Craig Price has watched us from prison, as through a one-way mirror. He reads about us in the local papers. He listens to us on the radio. From his cell in the High Security Center in Cranston, he sees our headlights on Route 37.

Price turned 30 last October, in an 11-by-7 compartment in the warehouse of our worst offenders.

He has already served his time for murder as a juvenile. He is doing 17 years for contempt of court, and is due for release in 2022.

The scar from the wound he inflicted on himself in the Heaton home rings the second knuckle of his left index finger. The cut didn’t heal right; the finger won’t bend all the way.

Rhode Island never healed right, either.

Craig Price, in his own words, has become our “official state demon.”

He was a frightening blend of brutality and physical power — 235 pounds in the ninth grade — who crawled into your home at night, seemingly killed at random and showed no remorse. Price maintains that “the demon thing” also has an element of racism; that mostly white Rhode Island more readily imagines devil horns on black skin.

Radio callers openly rooted for his assassination when he came up for parole in 2002.

It is commonly believed that the legal system twisted itself to find ways to keep Craig Price locked up — but that in this one special case, that’s OK.

Price complains the state has plotted to keep him caged, and he’s right.

He wouldn’t let the state psychiatrists into his head; for that, the courts ruled him in contempt and put him away.

And we never learned why. Why did he do it? Why Becky Spencer? Why the Heatons?

Two years ago, I asked Craig Price. I asked him why. This was not about whether he should be free, or whether he should never be free. It was about how one middle-class suburban kid winds up in your bedroom with a 10-inch blade.

Through letters and interviews, Price described how he came to kill.

He also told of two people who got away, who never knew how near death had come.

Some of his story can be verified, and some cannot. But it rings as a truer confession than the lie he told police in 1989: that he had killed to cover robberies gone wrong.

He is a fiercely proud person, even today, and it took months to learn what he hopes to gain from talking. It is something that speaks to what it is to be human, and it poses a new question about Craig Price.

Forgiveness, he thinks, is not possible for someone whose every breath is an agony for two families destroyed. “Not unless I take a bullet for Bush, save every kid from a fire at Hasbro Hospital and win every medal in the Olympics,” Price says dryly.

But is it possible that a monster becomes a man?

The harder you look for the answer, the bigger the question becomes.

A FINAL PUFF and it was done.

Thirteen-year-old Craig Price blew marijuana smoke out his bedroom window, and then hefted his Black Magic aluminum baseball bat onto his shoulder.

He had organized his thoughts and dispelled the confusion he had felt earlier. He was still enraged, but outwardly calm, stoned on pot, and high with a lust for murder.

From his bedroom, he plotted:

Hide in the bushes by the door.

Wait.

Smash their skulls.

His father had already left for the night shift; his sister was staying with friends. His mother and brother had fallen asleep.

Craig Price ducked outside. This July night in 1987 was warm, around 70 degrees, the wind light and steady. The moon had risen in a crescent, and had already sunk below the horizon, leaving a star-filled sky over Warwick. Backyards were dark. The trees looked like shadows on black velvet. He made for a three-bedroom ranch, two houses away. It was much like the Price family home, like most every house in this part of middle-class Buttonwoods.

With every fiber of my being I wanted nothing more than to kill.

He did not know the names of the visitors he wanted to murder, but he knew the woman they were visiting, and she would pay, too.

She was Becky — Rebecca Spencer — his neighbor for the past year at 60 Inez Ave., a house she rented with one of her brothers. Becky Spencer was 27. She had four brothers, three sisters, a close former husband, a mother, a father, a stepfather, a son and a daughter. Craig Price remembered playing touch football in the street with her son.

Price was 200 pounds and in seventh grade. He had dressed in black.

He ran with his bat across his parents’ lawn to a backyard fence, and looked to Spencer’s driveway.

He stiffened in disbelief, his breath snatched as if from a body blow. The car was gone; they had left.

Disappointment pooled in his gut. He had stopped to smoke one more joint, and he had missed them. Craig Price dropped, deflated, to the grass and gazed into the night. The dampness of the ground agitated him. He felt like lashing out, but there was no one to kill.

Why? Why Why Why Why did I have to miss the opportunity,

His marijuana high faded and he wanted a new one. He hauled himself up and crept inside his house. Upstairs in his room, he packed his pipe. It gave him a bad high. Every hit of pot he blew out the window toward Becky Spencer’s house reminded him that he had failed. The more he smoked, the more he dwelt upon his missed opportunity, that he had missed his chance to get even.

Or had he?

He could go back to the Spencer home and vandalize the place while nobody was around — lash out against the house.

Craig Price finished smoking. He left the baseball bat behind, and set back out with a fresh high.

He hopped the fence and stole across his neighbor’s backyard. He scaled the next fence, and dropped into the far back corner of Becky Spencer’s yard. There he crouched, motionless, and let his eyes adjust.

The yard had not been mowed in a long while; patches of grass were thigh-high. He felt wild in the overgrowth, like a hunter.

The house was quiet. The only light was a dim flickering, deep inside, maybe from a television. Price peered into the first window, a bedroom cluttered with cardboard boxes. What he had heard around the neighborhood seemed true — Becky Spencer and her brother Carl Battey were moving.

The shade was partly down at the next window, probably a bathroom. Nobody was there.

Next window: the kitchen. It was littered with pans and dishes and more boxes everywhere. They were moving out, for sure, and soon.

The next window was the dining room. It was in disarray, strewn with junk and more boxes. Through the dining room, he could see into a living room lit by the television.

Someone was there.

He saw a figure under a blue blanket, lying on the carpet in a room with no furniture. From the brown head of hair resting on a pillow, he guessed it was Carl, Becky Spencer’s brother and housemate.

As he stared, he sensed something touch the back of his legs. He jumped aside, startled.

A cat.

Just a tabby cat.

Price stomped his foot. The cat dashed through a door left ajar in the back of the house.

Craig Price crept to the door and slipped silently within.

The house had a papery smell, like a well-used library book. The room seemed even darker than the outside. He could make out a big black chair and more boxes. Around a corner was the flickering television. He tiptoed to the kitchen, and then peered into the living room.

Becky Spencer, in a lilac nightgown, was asleep on the floor.

She was 5 feet 4 1/2 inches tall, 142 pounds, and looked younger than 27. Her eyebrows were thin brown lines, and she wore dark blue eyeliner on her upper lids. Her fingernails and toenails were painted pink, her face and arms nicely tanned. She wore a ring on each hand.

The television was tuned to VH-1, a music video channel.

Price tensed. He eased back to the dark room, where he had first entered the house. His stomach was boiling, his mind a cyclone.

He reclined in the big black chair and wondered what to do about the house, his plan to vandalize the place, and the woman sleeping in the next room. His first thought was to rob the house and burn it down.

No good, he thought. No matches.

Then he thought about rigging the wiring to start a fire. Maybe heave a cinderblock through the window, too.

Craig Price decided he needed a weapon. He picked up a frying pan and swung it through the air. It was too clumsy. He gently put it down and looked around some more. That’s when he found a 10-inch carving knife. The instant he grabbed the handle, he sensed his plot moving from theory to reality, and he felt a chill.

No more room for imagination.

He went to Becky Spencer and stood over her. How long? He couldn’t say. Eventually, he realized he had been staring at her.

Then Price looked around, suddenly lost. He froze in place and a mental haze settled over him. Memories of scores that needed settling — some distant and faded, some fresh and still jagged — bombarded him. The music video “Let’s Dance” by David Bowie was on the TV.

Silence blended back into my mind . . . I listened, transfixed by the silence, and let the parade of memories march away into the darkness . . . I can remember being drawn into the throbbing blue light the television was giving off. A strange sense of awareness settled upon me and with this awareness came this raw and savage sense of outrage that completely consumed me. It was time (to) kill.

THE THIRD CHILD of John and Shirley Price had a teeny beginning for someone who would grow to more than 300 pounds. He was born at 6 pounds 8 1/2 ounces, on Oct. 11, 1973, in Cambridge, Mass., where John and Shirley Price were living with their daughter, Kimberly, and son, John Jr.

Shirley Price named their son from a book of baby names:

Craig Chandler Price.

He grew up in a household of devout Baptists.

John and Shirley had met in 1967 through their church, Concord Baptist, in Boston. Their families were close, sang in the same choir. Shirley Price’s sister is an ordained minister. So was her grandfather.

They married in 1968. Kimberly was born that August. John Jr. was born in 1972.

John and Shirley would often remind their kids that they were children of God, entrusted to human parents who were duty bound to teach them how to live for the little while they were on this earth.

Young Craig Price had a gift for cracking up his parents. When he was about 5, the family pastor prophesied to Shirley Price that there was greatness in little Craig, that there was something important the child would have to do.

Shirley Price thought that was funny. “Oh, he’s just a little jokester,” she told the pastor. “He makes you laugh.”

Shirley E. Price, now 55, was born in South Carolina. She moved to Boston with her family at 16 and graduated from an all-girls high school. She attended college for about three semesters, and then went to work. In the late 1980s, she was a clerical worker at Brown & Sharpe and held down a second job at a Kmart.

John C. Price, 57, is from Mississippi. He moved to Boston in 1965 with his family, attended a tech school and then went to work. At the time of the homicides in the late 1980s, he was a manager at Pepsi-Cola Co., in Cranston. Craig Price grew up avoiding soft drinks that weren’t produced by Pepsi. He wore a Pepsi windbreaker and plastered everything he owned with Pepsi stickers from his dad.

John and Shirley told Training School officials in the late 1980s that their household income was “in the $50,000 range.”

The Price family moved in 1978 to 76 Inez Ave., in the Buttonwoods section of Warwick, a cluster of ranch-style houses crammed back-to-back on parallel streets. Shirley Price chose the city for its public schools.

As a youngster, their son Craig was accident-prone — always rushing around, sometimes not watching where he was going. He slipped unnoticed out of the house at age 3, was hit by a car and hurt his leg. He had stitches when he was about 7, after being hit on the head with a rock. A year or two later, he fell off a chair and broke his collarbone.

Craig Price loved football and baseball, and playing his fire-red electric guitar. He was good at sports and he didn’t care if he won or lost. He was a blue jeans and T-shirt kid, who liked hard rock and rap music.

He was a storyteller, a mimic, practically a standup comic, described as a “big marshmallow” and a pied piper, always surrounded by friends. He could be a wiseguy around authority, but was respectful to grownups in the neighborhood, quick to offer his strong back to shovel snow or cut some grass.

His teachers at Warwick Veterans Memorial High School thought he was bright — in state custody at age 15, he tested above his grade level in reading and spelling — but that he didn’t try. He cut class, and had to repeat seventh grade.

He discovered cigarettes and drugs, beach parties, petty theft and car smash-and-grabs. He argued with his parents, wound up in juvenile court and was put on probation.

One time when he came home tripping on LSD, his mother stuffed him in the car and sped to Boston, to see Craig’s aunt and both his grandmothers. They sat him down and shouted Scripture at him. His altered brain warped the stories of angels and serpents into psychedelic visions. At the end, the women cried and hugged him and told him he was cured of his want for drugs.

While Price had his problems, he was the youngest member of an intact, working family on its own little squared-off parcel of America, with a driveway, a bit of lawn and a garden shed out back.

The shed was where the police would find knives stained with blood.

THE BUNKER-LIKE High Security Center at the Adult Correctional Institutions looks harshly chiseled from one giant slab of masonry. In the waiting room, two rows of molded plastic chairs are bolted on rails. On hot days, the desk officer props open a side door with a sack of concrete mix.

The Department of Corrections calls the 23-year-old HSC its “end of the line,” a depository for the hardest criminals and the most unruly, not to be confused with the Maximum Security complex down the road, which is not really the maximum. The HSC is called Supermax.

A correctional officer, dressed in a slate gray uniform with black piping down the trousers, enters the waiting room one minute before visiting time. From a drawer he produces a sign-in sheet for the visitors. There’s a box to check off if you’ve ever been convicted of a felony.

The officer hollers, “Thirty-four!”

A steel door, beige with a white “34” stenciled on it, buzzes open. It leads into a security airlock — the doors on either end never open at the same time — and then into a long, narrow visiting room. Twelve blue plastic swivel chairs face into partitioned booths. Each booth has a telephone to talk to the inmate on the other side of the glass, like in the movies. The glass is smeared on my side with tiny handprints, from a child who reached for a man on the other side.

Prison is about time. You do your time, serve your time. Yet the clock on the wall is wrong by an hour, and nobody ever fixes it.

There are rarely more than three or four visitors here, except around Thanksgiving and Christmas. The visitors seem to be mostly women. Maybe half are mothers, loyal to their sons. There are young women, too — some with babies — who offer a different kind of loyalty to the men behind the glass.

My first of some 30 visits with Craig Price was June 11, 2002.

Craig Price is 5 feet 10 inches tall, 300 pounds, give or take a couple dozen. He doesn’t ripple with muscle like a bodybuilder; he is shaped like an oil drum, with the all-over bulk of a furniture mover, strong for strong’s sake, not for vanity. His personal best at the bench press is 485 pounds, though he hasn’t had access to weights in years.

He wears a trimmed Vandyke-style beard and keeps his hair buzzed short. While the other inmates are often unkempt, he is always groomed. He dresses in an orange jumpsuit, size XXXXL. A tan patch over the chest pocket identifies Price as inmate 095484. He wears a black plastic sports watch, and handcuffs.

We pick up the telephones. They are in poor shape. The parties to this prison conversation are three feet apart, yet the line crackles as if we are speaking from across the world.

“Did you sign that consent form when you came in?” Price asks at once.

“I signed . . . something.”

He frowns. “You just consented to a strip search on your way out.”

I try to remember the warnings about drug smuggling posted in red letters in English and Spanish on the waiting room wall. My brain is not ready to deal with dropping my pants in Supermax.

Craig Price looks sly for a second, and then smiles. “Naw,” he says, “I’m just messing with you.”

His eyes are bright, none the worse for what they have seen. He shuts them hard when he laughs — yes, he can laugh. He scrunches his face like a raisin, holds the telephone at arm’s length and leans back like he’s about to tip. Then he convulses up and down, a pile-driver of laughter.

He is still a storyteller, who starts with a point and then quickly veers off, talks a giant wandering circle, and then comes back to the subject at hand. Visiting time runs 90 minutes, and he’d talk the whole 90 if you let him.

He punctuates his stories with impersonations, funny voices and accents. He does a generic impression of The Man, to imitate judges and cops and prison brass. It combines a heavy scowl with verbose legal language and a leaden tone, weighted with contempt.

He seems in good spirits this first visit — bitter about being locked up, but hopeful about his appeal, filed in early 2002 in the Rhode Island Supreme Court.

Over the next year, his mood would change, growing ever darker as his hope to overturn his sentence in the state courts dimmed.

Craig Price speaks like a well-read person who enjoys exercising his vocabulary, mixing long words and formal grammar with prison slang. One time, he asked how to pronounce feng shui, a term he had seen in print but had never heard spoken aloud. He doesn’t swear at all the first day, but does casually in later visits, though no more often than the average journalist in a newsroom.

Rhode Island law in 1989 did not permit the state to hold minors past their 21st birthday, no matter what their crime. Price will allow that he didn’t get the sentence one would deserve for four murders, but says that under the law, he has paid for those crimes in full.

He wants to talk about his “perpetual persecution” from the authorities –the alleged harassment, set-ups and cover-ups. He says they are trying to drive him to more violence, even to kill, so they can lock him up forever.

“I am being provoked beyond all endurable standards,” he writes to me. “These people are fascinated with raw violence and I am absolutely sure these drama freaks are trying their hardest to coerce me into an unrestrained demonstration of brutality.”

In a visit, he says, “I feel like I’ve got this little flame of hope that I’m trying to protect.” He cups his hands around an imaginary candle that represents freedom. “And everybody just keeps blowing at it.”

If that candle were to go out — if freedom became impossible — then Price would have to let go of the outside world and accept prison as his life, he says. He has so much hope and emotion bound up in his appeal, he hardly wants to think about what would happen if it fails.

“There is nothing more dangerous,” he says, “than a man without hope.”

I want to hear his story, but it has to be the whole story. The homicides. The mystery. Everything.

“I can be candid,” he says. “It would hurt my mom, but I can do it.”

I had assumed that he meant churning up his past would hurt his mom, but that wasn’t it at all, though I wouldn’t learn the full story for nearly a year. Until his mother told me herself.

THE FIRST clinical psychologist to peer into Craig Price’s mind saw anger behind his smile.

Dr. Spencer DeVault evaluated Price in October 1989, the month after the Heaton murders, over four sessions at the state Training School. DeVault concentrated on psychological and personality testing, leaving the details of the crimes for other doctors to explore.

Price had just turned 16.

“He impressed the examiner as a well-spoken, articulate young man who did not seem at all anxious, and who was on this occasion, as on the succeeding three dates, completely cooperative,” DeVault wrote in his report.

Price never became hostile or negative. He maintained good humor. But DeVault thought Price’s responses showed a lack of empathy for others and an “intense conflict underlying Craig’s apparently affable demeanor.”

Price saw Viking and barbarian helmets and shields in the Rorschach inkblot test. He answered “true” to true-and-false questions that explored whether he had a hot temper. DeVault administered a fill-in-the-blank test that provided Price a word or two that he had to expand into a sentence. His answers, in italics, don’t seem revealing on some questions, but from others DeVault inferred some regret and a lack of remorse:

I like to play a lot of sports.

The happiest time is at Christmas time.

A mother and her child ate dinner.

My greatest fear is sharks, heights and needles.

I hate to eat vegetables.

I regret some of the things I did in the past.

When I was younger I did a lot of crazy stuff.

My greatest worry is my family.

I feel that I should have a pardon.

The only trouble I have is not having freedom.

I wish I could turn back the clock.

“He appears to be a young man limited in the available resources for coping with stress and vulnerable to being overwhelmed by stimulus demands, both from his own emotional pressures and from the environment. Predicted as a result would be disorganization and a loss of control,” DeVault wrote.

“This teenager believes that past degradations may be undone by provoking fear and intimidation in others . . . He is rarely able to submerge the memories of past humiliations and this resentment may break through his controls in impulsive and irrational anger.”

DeVault recognized the limitation of the tests to reveal why this affable teenager murdered his neighbors. “There are many questions unanswered by this evaluation,” he wrote.

But DeVault had discovered a larger truth behind the crimes.

Past humiliations. Impulsive and irrational anger.

CRAIG PRICE is locked alone 23 hours most days, in a cell with a concrete floor, a bunk, a metal toilet and a steel door. For an hour a day, he can wander outdoors in a little courtyard, enclosed in a pen. There is time for showers and 90 minutes of visitation per week — if anybody shows up.

His mother has been a frequent visitor to Supermax. Craig Price thinks of her “like my best friend.” He doesn’t communicate as well with his father, and sees him less often, maybe one or two times a year. His parents are still together, married 36 years.

Price reads most of the time. He has read about three books a week for more than a decade. In one week he read: The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ, an alternate theory on the history of Christianity; A Contemporary Reading of the Spiritual Exercises: A Companion to St. Ignatius’ Text; and Wonderful Ethiopians of The Ancient Cushite Empire, a history of Africa. He had also started The Wishsong of Shannara, by fantasy novelist Terry Brooks. Price is a Brooks fan. “The characters take you away,” he says.

“I try to keep my mind busy and I try to keep my plate filled with knowledge,” he writes to me. “All that I study and read is useful, because what good is knowledge if it has no purpose and will not be exercised to elevate self and others in your midst?”

Price also reads law books. He wants to understand how the state locked him up, so he can help get himself out.

Price does pushups by the thousands, and other calisthenics and body-weight exercises. He walks a mile a day in his cell. He’ll count 5,300 tiny steps, back-and-forth, just over a mile.

The prisoners yell to each other out their doors. They trade stuff by “fishing” — passing small items along string under their cell doors.

Price and the men around him formed a chess league, each man with his own chess set made of chits of paper. They shout moves to each other. Everyone in the club has to call the reigning champ “The King.”

Price’s neighbor stopped playing chess. Just got depressed, or something, and stopped playing. Price was mad at losing one of the few things that elevates the mind in prison. “If he wasn’t my friend,” he says, “I’d fight him.”

The prisoners are fed through slots in the doors. They are allowed to buy things like peanut butter and bread if they have somebody on the outside who cares enough to put money into their ACI accounts. Price’s mother occasionally makes a deposit.

The inmates also learn how to make weapons — nearly anything made of metal can be ground down and sharpened against concrete, even serrated with a thousand strokes over an iron bunk rail.

Price used to smoke before the prison banned tobacco a year ago. He liked watching his smoke rings. Just about anything can be entertainment in prison. The men gather at their windows to watch two wild rabbits that live near Supermax. The rabbits run at each other in some kind of game. An inmate banged on his window one time to scare the bunnies and wreck the show. The men around him threatened his life.

Price listens to his Walkman radio every day. He catches the Providence talk shows and most Red Sox and PawSox games. He predicted last year that Boston’s “closer by committee” bullpen would be a disaster. And he has argued that the New England Patriots should have kept quarterback Drew Bledsoe over Tom Brady, though he’s now changing his mind.

He asks me about movies. Did you see that one with Mel Gibson? Signs? Sounds amazing! Did you see it? You did! Is it amazing? Sometimes he just wants to hear about what I do when I’m not working. Did I go anywhere? Do anything? Anything? It’s as if his imagination has run low of material for his fantasies about being free.

Late at night, when the cellblock is still, Price looks out the single narrow window in his cell. He can make out cars on Route 37.

I’ll watch until four cars pass, he tells himself.

He enjoys the peace, and wishes that he could do the rest of his time with things just as they are.

CRAIG PRICE was 9 or 10, by his best recollection, the first time he wished that someone would die. It was August. He was about to race his new “Road Runner” bicycle against a Buttonwoods kid with a new Huffy.

Price adored his bike from the moment he got it. It had deep Y-framed handlebars and blue finger grips sprouting sky-blue tassels. His favorite part of the bike was the sparkly blue chain guard, on which white letters spelled out “The Road Runner.” He had decorated the chain guard with Pepsi stickers, and renamed his bike the Pepsi Road Runner.

Price was wearing a blue Pepsi T-shirt, blue Pepsi jogging pants and blue sneakers with Pepsi reflection stickers on the heels. His father’s Pepsi work helmet sank low on his head.

But as the race was about to start, he says he heard someone yell, “Hey spearchucker!”

A cold fear gripped my stomach and a nervous lump began to grow in my throat . . . Mostly out of fear and perhaps out of a small muster of defiance and courage, I consciously ignored whatever idiot was calling me.

A golf ball hit the pavement and bounced against his leg. Price turned around. An older kid, maybe 19, with straggly hair, was glaring at Price from a driveway. The guy had two friends with him.

“Did you steal that bike, you . . . nigger?”

Paralyzed with raw fear now I just lowered my head and wished these idiots would get swallowed up by the earth.

They threw another golf ball at him, and more slurs, and then headed to a car, a beat-up Mustang.

The kids got on with their bicycle race.

Price says he heard an engine roar, and that the Mustang pulled up alongside of him. The kids inside screamed racial slurs.

I just went into a panic and tried to literally out-run this car . . . I really thought these [expletives] wanted to kill me.

He pedaled into a curb and dumped the bike. He mangled the chain guard, tilted the seat and bent the handlebars.

Price wanted those kids to die.

He picked up his busted bike and went home. His father was mad about the damage. Craig Price choked on tears. He managed to blurt, “I was racing . . . “

That was as far as he got. His father spanked him because he wasn’t supposed to be racing. The sting quickly faded, but he says he never shed the feeling of injustice.

It could most definitely be said that the Pepsi Road Runner situation was among the earliest kindling that nourished the flame that consumed my life and the life of others.

PRICE OFFERS this logic:

Emotions affect actions, thoughts affect emotion, the brain creates thought, chemicals affect the brain. But what if one part of the chain malfunctions? What if somebody can’t burn off an emotion as strong as anger?

Price says he didn’t develop an outlet for anger when he was a child.

Welled inside him, “maybe that anger grew in an unnatural way,” he theorizes.

Eventually, the anger released all at once like a geyser.

Price traces the seed of this emotion, the earliest link on the chain, to racism.

He sends by mail a 13-page paper by Alan B. Feinstein, a psychologist for the Department of Corrections (not the Rhode Island philanthropist of a similar name).

The paper “explores the possible role of [Craig Price’s] exposure to racism as a factor in the murders,” Feinstein writes in a brief introduction. While other factors were present in Price’s psyche, “years of experiencing both overt and covert forms of racism appear to have had a significant impact on his psychological functioning and ultimate acts of aggression.”

Feinstein has interviewed Price many times in prison.

“Throughout the interview process, I was struck by C.P.’s numerous stories of racial mistreatment and the effect they had on him. These events were related in such detail it was as though they had occurred only yesterday, rather than in some cases, over twenty years ago.”

Like the time he was 5 and other kids wondered “where his tail is.” Like when other kids were served soda in glasses and he was the only one with a paper cup.

“Interviews conducted with C.P. indicate that his victims were not chosen at random or as a matter of convenience, but rather due to their being associated with some perceived racial slight directed toward him.”

The stories of racism were vivid, but Feinstein could not be sure they were all true. “The possibility exists,” Feinstein allowed, “that C.P. possessed a pre-existing paranoid trait which then caused him to perceive mistreatment that was non-existent.”

Real? Or just real to him?

Either way, the pressure builds.

THIRTEEN-YEAR-OLD Craig Price heaved the football over his brother’s head to a teammate racing down the street.

Intercepted!

No! Pass interference!

The argument raged in the street, the players offering their memories of the catch as instant replays.

That’s when Craig Price says he heard a racial slur, in a man’s voice, coming from a car stopped in front of Becky Spencer’s house.

I was heated, but just like many times before when this kind of situation presented itself, I simply said nothing and didn’t do anything, and just like many times before, I grew angry and outraged at myself.

But the anger he tried to stuff down inside wouldn’t fit. He tried to shrug it off, telling himself that he was tired.

I felt out of my element, and my inability to cope with this stress left me face to face with the strongest desire to murder.

For one more week, Craig Price was still just a kid, a kid whiling away his summer vacation with his friends in the neighborhood.

For one more week.

AS DUSK fell, Craig Price shared marijuana with a friend, and then joined the neighborhood kids for a round of “manhunt,” a hide-and-seek game with teams.

Craig Price was on the team he liked best, the hunting team.

The game stretched across Inez Avenue, in driveways and backyards, over fences and under shrubs. Parents of the players, including Price’s father, would tell the kids to stay out of other people’s yards, but what fun was that?

Throughout the game, Price and his friend kept smoking.

Price tagged two kids at about 9 p.m. and escorted them to a utility pole that served as the jail.

That’s when a white car coming down the street interrupted the game.

In a statement to the police the next day, one of the kids would say that the man driving the car hollered at them about being in the street, and that he made some comment that they could get run over next time.

Craig Price would tell the police in a written statement that the driver had blared his horn at the kids, and that Price had seen the man at Becky Spencer’s house about a week earlier.

Years later, Price would allege that the driver was the one who made the racial remark Price had heard the prior week. On the night of the manhunt game, Price says, the man rolled down his window and called Price another racial name.

I was completely outraged. Outraged by this guy almost hitting us with his stupid car, outraged by this [expletive] calling me a spook, and most of all I was unyieldingly outraged at my own self for just standing there and not saying or doing anything.

After the game, a few kids hung around outside Price’s house. Price kept to himself — he was obsessing with raw and powerful thoughts and did not want to betray the firestorm inside him.

I simply could not banish from my mind the fact that I not only wanted to kill, but had to kill . . . And so, on the night of July 27th, my mind was made up to murder.

Late that night, he dug out his Black Magic aluminum baseball bat.

JULY 27, a Monday.

The lease was up in four days and Becky Spencer, her children, Steven and Danielle, and her brother Carl Battey had to move from the brown house they had rented for the past year. Most of the furniture had already been moved; Becky’s bed was gone. Carl had stopped their newspaper delivery. The house was choked with cardboard boxes.

Becky Spencer was uprooting and moving again. She had moved on before, when her mother remarried and left the state. Becky had lived with a friend’s parents in North Kingstown. She moved on again after her marriage to Steven Spencer broke up, though they remained close.

There was a time when Becky Spencer seemed like the luckiest person in Rhode Island. Just five years before, Becky and Steven had won $48,754 on a $2 lottery bet, after five months of playing the same number twice a week: 01-22-25-28, taken from birthdays in the family.

Now divorced and in her late 20s, Becky had decided to make her own luck. She had earned her high school equivalency diploma the year before, and had told her ex-husband that she planned to attend college at night. She wanted to do better than her $5-per-hour job at a Warwick jewelry company.

She spent her last day doing errands.

Her kids, Steven Jr., 8, and Danielle, 4, were with their father that day. A girlfriend of Becky’s arrived to help pack up the house. That afternoon, the women dashed off to Fleet Bank in Apponaug to withdraw $80 to pay for storage space.

That evening, Becky cooked chicken with gravy, mashed potatoes, corn and a salad. Carl, a security guard, joined Becky and her friend at dinner, before he headed to work on an all-night shift.

The women started packing.

At about 9 p.m., another visitor arrived, a guy Becky’s friend was dating.

He would tell the police the next day that he had noticed a bunch of kids playing in front of Becky’s house when he had pulled up. His statement does not say what he said to them.

The women took a break from packing and they all watched music videos on VH-1.

Becky suggested around 9:30 that they go out for ice cream, which became a two-hour expedition: to Cumberland Farms for cigarettes, Friendly’s on Reservoir Avenue in Cranston for ice cream, a hot-dog stand for wieners and fries, to the guy’s house in Cranston to see his dog, and then back toward Buttonwoods.

Becky, wearing jeans and a blue terry-cloth top, fell asleep in the car.

They woke her at her house, and all three went inside.

It was nearly midnight when Becky’s visitors left.

Alone in a nearly emptied house, Becky Spencer changed into a lilac nightgown, and then settled under a blanket on the living room floor.

She fell asleep to music videos on VH-1.

THE FIRST BLOW buried the blade almost to the hilt. Price stabbed until she stopped moving, until he was sure she was dead.

Fifty-eight times.

He was struck by the darkness of blood when there was a lot of it. In a panic, Craig Price burst from Spencer’s home. When he got to the fence and tried to climb it, he saw that he still held the knife. He flung it and ran.

Back in his own yard, Price was safe for only a moment, then remembered the frying pan in Becky Spencer’s kitchen. He had touched it. He thought about fingerprints.

Gotta go back for it.

Over the fence he dashed again, back to Spencer’s house. The place reeked of blood, a thick metallic odor. He could almost feel the stench sitting heavy at the back of his throat. Price grabbed the frying pan and fled.

Outside, the pan suddenly seemed ridiculous.

He tossed the pan in the bushes and ran down Spencer’s driveway, down the street to his home. He stalked outside his own house until he was sure nobody was up. Then he slinked inside, up to his room and shed his bloody clothes. He stuffed the clothing in a bag and hid it in the attic. Then he tiptoed downstairs, to the bathroom, and washed the blood from his skin.

Back in his bedroom, he closed the door, packed his pipe and smoked.

I was on edge and I didn’t want to freak myself out so I laid down in my bed to go to sleep.

He stared at his hands. The blood was gone, down the sink, yet his hands looked different. They looked bigger.

His longhaired orange cat, Jay Jay, snoozed nearby on a chair. Price got the cat and brought it to his bed. He held the cat to his chest, glad for its company, and drifted off to sleep, seeking comfort in an irrational hope that nobody would ever notice what he had done.

Craig Price gets 25 years in stabbing of inmate

By Katie Mulvaney

Journal Staff Writer

Posted Jan 18, 2019

Price, now 45, ranks as perhaps Rhode Island’s most notorious criminal, committing murder at the age of 13.

PROVIDENCE — A Florida judge on Friday sentenced infamous serial killer Craig Price, who terrorized Warwick in the 1980s, to serve 25 years in prison for trying to murder a fellow inmate.

Price, 45, agreed to plead guilty to a charge that he stabbed inmate Joshua Davis with a homemade, 5-inch knife blade at the Suwannee Correctional Institution, according to the Suwannee County Clerk of the Circuit Court’s office. He received a 25-year sentence on that charge, plus 10 years’ probation, according to Assistant State Attorney Sandra L. Rosendale.

He received 10 years’ probation for possession of contraband. The probation terms are concurrent, but will be served consecutively to his prison sentence, Rosendale said.

Price agreed to waive 524 days of good-time credit, the clerk’s office said.

If Price violates his probation upon his release, he could be sent back to prison to serve a sentence up to life, Rosendale wrote in an email.

He agreed to be classified as a habitual felony offender.

Rhode Island prosecutors praised the resolution of the case.

“We are extremely grateful for the excellent work by the Third Judicial Circuit of Florida State Attorney’s Office on this case,” Kristy dosReis, spokeswoman for Attorney General Peter F. Neronha’s office, said in an email statement. “It has been clear from the beginning that our Florida colleagues knew how significant this case was to Rhode Island. We are also grateful that, for purposes of public safety, Mr. Price has been sentenced to a long sentence based on his latest acts of violent criminal misconduct.”

Price’s lawyer, Michael Bryant, declined comment.

Documents indicate that Price entered Davis’ cell on April 4, 2017, and repeatedly stabbed him. Davis fled, but Price tackled him and continued the attack. Authorities say the premeditated assault was caught on video and that Price intended to inflict mortal wounds.

Price was arraigned in August 2017, but had refused to enter a plea, instead reserving his right to challenge the legal sufficiency of the charging document, prosecutors said. His trial was repeatedly delayed and, in November, his lawyer sought to get a competency assessment.

Price is perhaps Rhode Island’s most notorious criminal. In 1989, at age 15, he admitted to stabbing and bludgeoning his neighbors — Joan Heaton and her daughters, Melissa and Jennifer — in the Buttonwoods neighborhood of Warwick. He also admitted to committing the unsolved murder of another neighbor, Rebecca Spencer, two years earlier, when he was 13.

Under state law at the time, Price could not be tried and sentenced as an adult, meaning he would have been released from juvenile detention at age 21. He has since been held on a raft of charges, including contempt of court and assault on correctional officers in Rhode Island.

Price’s Rhode Island sentence ran out in October 2017, according to the state Department of Corrections. The Rhode Island attorney general’s office filed a probation violation petition against Price related to a previous Florida assault, a spokeswoman there has said.

More

Rhode Island Is Seeking to Keep a Killer of Four in Jail When He Reaches 21″ The New York Times.

Teen-ager charged in three homicides and 1987 slaying Spokane Chronicle